Category: Picky Eating

Budget-friendly bites: Navigating picky eating challenges in less time

Published by Courtney Bliss on Mar 19, 2024

When parenting a picky eater, we have to discard much of what we learn about food as adults. Diet recommendations to eat a lot of protein, avoid carbs and stay away from fat don’t translate well to kids’ diets –– especially to one who only eats a limited number of foods.

Good nutrition for children and adults involves a combination of different food groups over a week. The quality of that combination is known as the Healthy Eating Index, the gold standard for assessing nutrition.

Each macronutrient fuels the body differently. Some supply quick bursts of energy and others offer steady energy release.

This is why teaching kiddos to listen to their body signals is important. Intuitive eating means paying attention to hunger and fullness cues. This can be particularly challenging for children with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) because the anxiety of eating can mask hunger cues.

In some cases, the way we label food and the shame around it can make kids’ feeding worse. For picky eaters, worry less about food labels and instead focus on what nutrients are being delivered to your child’s body.

For example, here are some ways to reframe thinking around some typical foods for picky eaters:

- If your child only eats chicken nuggets, consider this a consistent protein and fat source that provides more steady energy.

- If your child only eats air-fried snap peas, this may not be fresh produce, but they’re still full of nutrients, fiber, protein and fat.

4 food categories kids need

There are four different macronutrients our bodies use. Each works a little differently.

Carbohydrates: Our bodies use carbohydrates quickly. They cause glucose to rise and enter the bloodstream faster.

Examples: Bread, crackers, pasta, cookies and cakes.

Fiber: This is technically part of the carbohydrate family, but our bodies don’t use it immediately for energy. Instead, our bodies use it to help food move slower through the bloodstream. They help with digestion and also make our energy last longer.

Examples: Fruits, snap peas, carrots, nuts, beans and whole grains.

Protein: Kids don’t require as much protein as adults. But, incorporating protein-rich foods into meals and snacks can help keep kids feeling full longer. To know how much your kiddo needs, consider protein intake over a week rather than obsessing over individual meals.

Examples: Chicken, fish, eggs, dairy, beans, nuts, nut butter and seeds.

Fat: This is the nutrient families skip the most, especially from parents raised in the 1980s and 1990s when fat was demonized. Fat is a core component to building hormones our bodies need. It releases energy slowly and keeps kids feeling full longer.

We need fat. Your kid needs fat. It’s building their brains and spinal cord. Don’t skip it.

Example: Peanut butter, cheese, avocado and foods cooked in olive oil.

How much of each nutrient your kiddo needs is super personalized. What’s true for everyone is that adding other nutrients to carbohydrates makes energy release longer. (Read: your kids won’t be asking you for snacks every five minutes!)

How to incorporate more healthy nutrition into your picky eater’s diet

In my years helping families of picky eaters, I have seen two common approaches to family meals:

- Those who serve family meals and accept that their child may or may not eat it.

- Those who make a completely separate meal.

If your goal is to get your kiddo to eat more variety and join the family dinner, taking a step back to plan can help you incorporate more of the true variety your kid will eat.

Following are five tips for families of picky eaters.

- Create a meal schedule.

- Combine nutrients for snacks and meals.

Each nutrient provides our body with energy in different ways. Combining foods helps your kiddo feel full longer. For example, eating a carb like a few graham crackers will give a quick burst of energy, but it won’t last. Adding peanut butter and apple slices to a graham cracker combines nutrients to provide a more filling snack. Pairing applesauce with some chips will keep your child full longer than just eating one macronutrient at a time. Eating this way doesn’t honor how the body metabolizes food and instead leans into fast energy releases.

Try to avoid: Providing free access to snacks, like applesauce pouches or a bag of chips, that are more likely to encourage grazing than satiety. - Look for brands with more balanced nutrition labels.

If your child is not particular about the brand you buy, you’ll find that some will have more fiber or protein than others. For example, if there are different kinds of cheese crackers and a nutritional difference, buy the more filling option.

Try to avoid: Feeling guilty about a processed food label when it’s one of few your child eats. Instead, focus on what nutrients might be in it and choose the best option your child will accept. - Make a meal plan based on what your child will eat.

Consider what foods your child eats and then combine them with other nutrients. For example, if your child eats waffles and blueberries, serving them together provides more nutritional balance. Combining “safe” foods over the course of the week will mean your kiddo gets more servings of nutrients like fiber and protein.

- Add some of your child’s “safe” foods to family meals.

Adding foods to family meals that your child likes might make your picky eater more interested. Write out a list of what your kiddo will eat. Then think creatively about how to turn that into five dinners you can rinse and repeat each week. For example, your kiddo loves apples and eats them whenever they’re served. Add apples to the family dinner rotation by serving them on the side, and your child might join the family at the table.

When your child isn’t grazing all day, you allow their body time to digest foods and then get hungry again. The food we eat sends chemical triggers from the belly to the brain. The sensations of feeling full and hungry are often diminished in children who are picky eaters.

Try to avoid: Constant access to snacks. Little bites at a time can reinforce picky eating.

Over the years, I’ve seen even the pickiest eaters increase nutritional variety with time and support. Know that the way your child eats now is not forever. Working on providing different foods is enough.

Courtney Bliss is the owner of Feeding Bliss and is an experienced registered dietitian specializing in pediatrics.

Feeding questionnaire a springboard for physical therapy needs

Published by Karen Crilly, PT DPT, Advanced clinical specialist at Texas Children’s Hospital on Oct 20, 2023

How one physical therapist uses the Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire to identify a child’s areas of need and how she can help

Feeding challenges never occur in a vacuum. While I’m neither a speech therapist or a feeding therapist, the Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire® (ICFQ©) from Feeding Matters remains one of my most important assessment tools in my initial encounters with new patients.

The ICFQ was authored in partnership with internationally renowned thought leaders representing multiple disciplines related to feeding. It’s an age-specific tool designed to identify potential feeding concerns and facilitate discussion with all members of the child’s healthcare team – including physical therapists (PT).

Based on the caregivers’ responses to six questions, the ICFQ has been shown to accurately identify and differentiate pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) from picky eating in children 0-4.

Using the feeding questionnaire as a physical therapist

Whenever I meet with a new PT pediatric patient at Texas Children’s Hospital, I spend the first session speaking to the family to determine how we can help the whole child.

For example, I recently was working with a family in the plagiocephaly – head-shaping – clinic at Texas Children’s. When I asked the parent about feeding, she responded that the baby just won’t stay still to eat. That response led me to ask more questions about feeding. I learned the baby has torticollis – tightness of neck muscle that causes the baby to turn to one side. Plus, the baby was dysregulated, which could mean a neurological issue. I asked about reflux, which could be a gastrointestinal issue. I knew how to help in some areas as a PT, and I knew to refer the family to an occupational therapist and a speech pathologist.

I can’t even describe how relieved this parent was. When it came to feeding, everyone else had simply told her to “keep trying.”

While physical therapy focuses on a child’s functional mobility, no movement’s isolated from the rest of a child’s health. Movement takes mental and physical regulation. An infant requires proper nutrition to perform at their highest level. A child without enough calories doesn’t have the necessary energy to make the most progress in physical therapy – or any other therapy, for that matter.

6 feeding questions that help me identify physical therapy patients’ needs

There are six basic questions on the ICFQ that clinicians identify when a child has a feeding issue. As a physical therapist, responses to the questions highlight issues around endurance, function level and the parent’s understanding of the child’s needs.

Following are the six questions and how the responses help me as a physical therapist.

- Does your child let you know when he/she is hungry?

This question gives me insight into how well parents understand their child’s communication cues. Recognizing an infant’s or nonverbal child’s cues allows parents to know when a child is hungry, uncomfortable or tired. This communication is essential to the parent’s ability to do PT exercises at home.

- Do you think your baby/child eats enough?

Often, the responses to this question are cultural. Among the patients I see at Texas Children’s, I find some cultures expect babies and children to eat more than others. This is an opportunity to educate parents about what is typical. For those babies and children not getting enough nutrition, it’s a chance to refer them to specialists who can help.

- Do you have to do anything special to help your baby/child eat?

This question helps me gauge a baby’s stamina level. The baby may be having trouble coordinating breathing with swallowing. This tells me that in physical therapy, I need to work on the baby’s ability to open her chest out wide and back in. The goal is to increase the baby’s endurance to work for 30 minutes of exercise. That causes fatigue at the time, but it actually builds stamina for later.

A baby who doesn’t have the endurance to finish feeding isn’t likely to have the energy to make as much progress in physical therapy. This makes getting more calories into the baby especially relevant for PT.

- Do you have to do anything special to help your baby/child eat?

This question helps me determine when a baby is dysregulated. It means I need to refer to a specialist who can help the family uncover why feeding isn’t typical.

In physical therapy, I’ll determine whether the child needs to work on muscle retraction. This is one of the issues I see often in infants, especially, and sometimes even older children who are having trouble feeding. Retraction takes them away from their midline without being able to find their center again easily. This makes it difficult to eat.

As a physical therapist, I’ll work with the baby on midline rotation. We work on coordinating the movement of opening and closing the arms and chest. The baby’s shoulders should expand back and then be able to come back to center. The baby should be able to find his flexion and make symmetrical motions in the upper and lower body.

Working on the body in this way can improve feeding, supporting the therapy that speech pathologists and occupational therapists are doing as well.

- Does your baby/child let you know when he is full?

When a baby is not recognizing fullness, this indicates there might be a chronic condition. Once full, a baby should cry, turn the head, push away the breast or bottle or spit out milk. But if a baby just keeps eating, this is a cue that the family needs a referral to a specialist.

As a physical therapist, it helps me identify a baby’s level of function.

- Based on the questions above, do you have concerns about your baby/child’s feeding?

Responses to this final question provide an opportunity for education. I’ll know how much information I should give parents on typical development for their child’s age and stage.

It’s also an opportunity to encourage parents who need a referral to go ahead and make that appointment.

As physical therapists, we’re not just looking at the legs and the feet. Treating our patients means treating the whole patient.

Knowing how a child is feeding doesn’t only alert me to a patient’s nutrition needs. It helps me identify other issues a child might be experiencing. Each question in the ICFQ paints a picture of the whole child’s needs.

Karen Crilly, PT, DPT, MAPT, CBIS, is an advanced clinical specialist at Texas Children’s Hospital who has dedicated her professional life to forming a strong background and expertise in the assessment and treatment of infants and children with chronic and complex developmental and/or neuro-motor impairment.

Focus on Food Safety

Published by Anna Busenburg, RD, CSP, LD, CLC on Sep 05, 2023

This blog post is published as part of a paid partnership between Feeding Matters and Reckitt Mead Johnson Nutrition. Learn more about our corporate partnership program and ethical standards for collaboration.

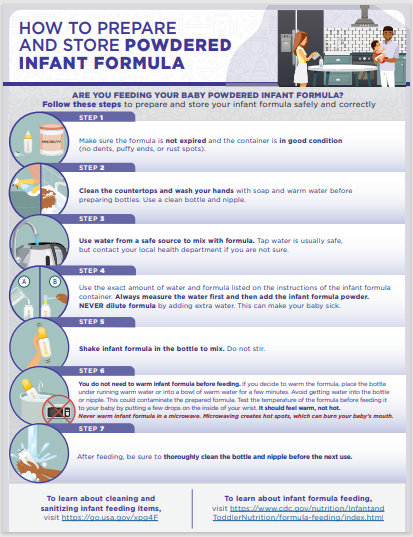

There are many opinions on using human milk or infant formula when it comes to feeding your baby. Most of the focus goes into what is being fed to your child, but less emphasis is placed on the safety of how feedings are prepared. Unless you are directly breastfeeding your child, you need to consider food safety when preparing infant bottles or tube feedings.

This focus on food safety has been front and center over the last couple of years since infant formula recalls have been in the news. These recalls occurred due to microorganism contamination concerns in a manufacturing facility. Food safety matters and is why liquid ready-to-feed or concentrated formulas undergo a heat treatment that sterilizes the product. Powder formulas are not sterilized, which poses an additional risk for contamination when incorrectly handled and prepared. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the regulatory and enforcement authority over the manufacturing and distributing of infant and pediatric formulas. It is important to consider food safety when preparing both infant formula (< 12 months old) and pediatric formulas (> 12 months old) being fed via a bottle or a feeding tube.

For families preparing pediatric feedings at home, it is important to remember these safety tips:

- properly wash your hands

- clean/sanitize feeding equipment and preparation space

- store prepared feedings appropriately

- follow the recipe from your provider

Practicing good hand washing techniques helps to diminish the risk of transmitting germs. Make sure that hands are washed for a full 20 seconds with soap and water. Proper handwashing is the #1 method of preventing the spread of germs for your child.

When bottles or pump parts are being used, cleaning them regularly is essential. It is also recommended to sterilize these components in the microwave or dishwasher. Any child that has complex medical conditions has increased susceptibility to infection. Steps to clean and sterilize equipment are crucial for these children’s overall health.

Any time you mix up formula – those feedings are good to use for 24 hours. Make sure that you label and note of when feedings are mixed and store in the refrigerator until it is time for the feeding. This includes recipes of human milk fortified with formula or formula only recipes. When warming infant feedings, never microwave. Options for warming include a bottle warmer or placing bottle in a warm water bath. When leaving the house with infant feedings, transport in a cooler with ice pack to help ensure the milk/water is kept cold to decrease risk of microbial growth.

When preparing your child’s feedings, follow the recipe on the can or given by your health care provider and check the expiration data prior to preparing. Some children need special feeding recipes to meet their growth goals. Use the scoop in the formula container or measuring utensil provided by your health care provider. Use a safe water source for mixing feedings, this can be tap water or nursery water.

Feeding your child seems like the most basic parenting task, but it can be challenging and complicated for many families. Remembering some of these guidelines of food safety can help ensure that you are doing the best for your child and keeping them safe. Click here to download and print handout from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) our HOW TO PREPARE (cdc.gov)

References:

1. Green Corkins, K., & Shurley, T. (2016). What’s in the Bottle? A Review of Infant Formulas. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 31(6), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533616669362

2. Turck, D. (2012). Safety Aspects in Preparation and Handling of Infant Food. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 60(3), 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338215

3. Green Corkins, K., & Shurley, T. (2016). What’s in the Bottle? A Review of Infant Formulas. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 31(6), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533616669362

4. CDC. (2018, May 7). Infant Formula Preparation and Storage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/infantandtoddlernutrition/formula-feeding/infant-formula-preparation-and-storage.html Accessed August 8th, 2023.

Anna Busenburg, RD, CSP, LD, CLC has been a registered dietitian for the past 11 years and specializes in pediatric nutrition and specifically neonatal nutrition, working in a level IV NICU at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. She has covered inpatient NICU and outpatient NICU follow-up clinic patients.

She has undertaken many projects over the years to help improve patient care and cultivate a culture to support nutrition education. She has been involved in developing a process for utilizing donor breast milk in a 25-bed NICU and she was involved with leading the launch of a breast milk/formula scanning system in a 100-bed NICU. Anna is a certified specialist in pediatrics and has completed the pediatric weight management course. She obtained her Certified Lactation Counselor credential in 2019.

She authored a chapter of the book The Nutrition Communications Guide from AND published in 2020 and published an article in the Pediatric Nutrition Practice Group on RDs Involvement in Infant Feeding Preparation Rooms published in 2019. She currently serves on multiple committees for the Pediatric Nutrition Practice Group and has held various positions within AND on the state and local level. She is also a member of the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. When not busy with work, Anna spends her extra time and energy with her family, which includes her husband, 3 boys, and a Chihuahua.

Pediatric feeding with empathy: 8 ways to think through a compassionate lens

Published by Marsha Dunn Klein, pediatric occupational therapist on Aug 17, 2023

On a vacation to Monterey, Mexico, I sat at a fancy restaurant and friends presented me with a plate of worms. Since I am a curious eater, and it was a delicacy, I cautiously took a bite.

At that moment, I couldn’t help but think of my feeding therapy clients. After decades as a pediatric occupational therapist, I wondered, “If somebody made you eat this, held your hands down while they put it in your mouth, or made you eat three bites of those worms before you could have your regular dinner, would that be fair?”

Understanding how children feel during mealtime is the pediatric feeding with empathy that I try to share in my teachings with parents and feeding therapists. Empathizing with why children struggle to eat or drink is key to setting clients up for a lifetime of better feeding. “We need to look deeper to find a compassionate lens. The foundation for supporting all areas of feeding therapy has to be fully cemented in an understanding of empathy, connection, safety, motivation, enjoyment and brain science.”

In a presentation at the International PFD Conference, I outlined eight mindset shifts to consider for a more empathetic approach to PFD feeding therapy.

Communicate the empathy circle

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. It’s the ability to sense another’s emotion and imagine walking in their shoes. For children and their parents, pediatric feeding with empathy means seeing food as they see it and reflecting to them that they’ve been understood.

Communicating what might be going on for a parent or the child is called the empathy circle. We need to find empathy for the child and what they might be going through. And we need to help parents have empathy for their child and understand what might be going on for them.

Look beyond just calories during mealtime

Nourishing children needs to include more than focusing on calories. Having a child feel like a celebrated part of mealtime is essential to skill mastery. Food is nourishment, but it’s also a means of communication and socialization. It can be about giving and receiving love, celebration and family time. This is why mealtime is an important opportunity to develop strong parent-and-child relationships. We need to ensure we’re also nourishing little souls with pleasant, safe company.

Shifting adult and child roles during meals

The role of adults at mealtime is to decide the menu and provide a safe environment for learning. When children come to the table, it’s to be nourished and have energy for the day. That means some of the foods offered at that mealtime must be foods the child knows and will comfortably eat while they’re learning about other foods that the family and siblings are eating.

Many of us have approached feeding therapy as if it’s our job to “get food into kids.” However, it’s the child’s job to decide what and if they’re going to put food in their mouths, and our job is to offer a variety of foods to allow for opportunity and learning about foods so the child can discover what he LOVES.

Rethink exposure to new foods

In the past, exposure to new foods meant getting a child to put it in their mouth. In some cases, a child gets pushed past their sensory safety zone. Exposure done with pressure can decrease the enjoyment of eating, along with any benefits of that exposure.

Asking a child with PFD to try a mouthful may be way too big of an ask. A little taste, lick, touch or even seeing others enjoy a food can be considered an “exposure.” Instead of thinking of “exposure” where adults often ask (or demand) that children interact with that food in a certain way, can we think of “opportunity” where the child gets to explore the food and decide if or when ready to try it on their own.

Work with the whole family

Both parents and children bring their experiences to the table. A trusted connection with parents from infancy supports a child’s ability to self-regulate. Feeding therapists must be sure to support parents’ success. This means asking assessment questions that reflect what’s going on with a child and parent. It also means including parents in planning and solutions with questions like: Of all the things we did today or talked about today, what would you like to try this week?

Consider why a child says no

A child says no to food for a reason, such as:

- They don’t feel well

- The sensory challenge is too great

- They have a difficult motor response to that food

- They have poor regulation

- They are too worried

Consider food refusal as communication. It invites us to be curious about what’s going on and how we can make that child feel more ready and safe for this mealtime interaction.

Shift from food tolerance to enjoyment

Tolerance is the capacity to endure pain or hardship. But enjoyment means satisfaction, pleasure and gratification. Food constitutes not only the taste but also sensory aspects, socialization, experience and satiation. Many of us have used the word “tolerance” in our feeding goals. But if a child doesn’t like that food, why would we settle for “tolerance” when we could aim for “enjoyment?”

Pay attention to communication cues

Forcing a child to eat when the adult is the more powerful figure in the relationship could mean missing cues of a child’s sense of safety, worries and need to protect themselves. It’s easy to push into their stress and worry zone and then call food refusal a behavior problem. This can unintentionally teach a child to ignore their body and sensory cues.

When we allow children to tune in to the wisdom of their own bodies, we’re supporting safety. Children who experience safety with us as parents and therapists are better able to regulate themselves. Pediatric feeding with empathy means seeing them, hearing them, valuing them and understanding them, to climb into their skin and walk around in it.

Ultimately, eating is a learned behavior. How parents and children interact over mealtimes matters. This is why parents and feeding therapists must do what they can to create positive memories around eating, food and mealtimes.

View Marsha’s International Pediatric Feeding Disorder Conference Session: Shifting our Focus in Pediatric Feeding Towards a Compassionate Lens here

Marsha Dunn Klein has spent over five decades working in feeding therapy as an occupational therapist, author, inventor and co-founder of the Get Permission Institute. This article is based on a presentation from the 2023 Feeding Matters International Conference.

Establishing a Self-Care Plan When Caring for a Child with Disabilities

Published by Dorothy Watson on May 04, 2023

This blog post was submitted by community member Dorothy Watson at mentalwellnesscenter.info. Interested in having your work on our blog? Learn more here.

Taking care of a child with disabilities can be incredibly rewarding, but it’s also incredibly challenging. The weight of responsibility and feeling of being overwhelmed can often lead to burnout for parents and caregivers. These individuals must make self-care an integral part of their plan to prevent burnout. This blog post will provide information and tips on how to create a sustainable self-care plan specifically designed for parents or caregivers of children with disabilities.

Learn To Recognize Triggers

The first step in creating an effective self-care plan is to identify triggers that cause stress, anxiety, or overwhelm. Identifying triggers allows individuals to recognize when they may be headed toward burnout and take steps to avoid it. For example, if going grocery shopping with your child causes high levels of stress, you can look for ways to make the experience easier or find alternatives such as ordering groceries online. Once you have identified your triggers, you can find ways to manage them proactively and prevent burnout from happening in the first place.

Assess Your Fatigue Levels

Caregivers should also become aware of their fatigue levels to create a successful self-care plan. When caring for someone who is on the autism spectrum, energy management becomes even more important as it can be easy to get burned out quickly due to constantly dealing with new challenges and trying different approaches.

Developing awareness around your energy levels will allow you to adjust your self-care plan accordingly when needed and create realistic expectations so that you don’t become overwhelmed by the tasks ahead of you. Sometimes, small changes like reducing clutter and spending more time in nature can be the boost that you need to get through the day. Both have been shown to reduce stress and life moods.

From Architectural Digest Reviews

According to a recent survey, around 33% of people report feeling extreme stress. Promoting a stress-free home environment has been linked to better physical and mental health. A peaceful home not only aids in sleep, reduces stress, and enhances overall well-being, but also boosts productivity and can help us find relief from the demands of daily life.

Our team believes that homeowners should feel at peace in their homes amidst their busy and hectic lives. We published a piece that includes ways to de-stress your home without sacrificing your style or time. Our team believes that homeowners should feel at peace in their homes amidst their busy and hectic lives. We published a piece that includes ways to de-stress your home without sacrificing your style or time.

Set A Few Personal Goals

Another important step in creating a sustainable self-care plan is setting realistic personal goals that are achievable within any given timeframe. Goals such as returning to school or finding a new job may seem out of reach at times, but utilizing tools like an online resume builder can be especially helpful in this process.

If you’re not sure where to get started, look for websites that allow you to choose a free professional template and add your own custom touches, such as an eye-catching font. If your goal is to start a business, look for help with forming an LLC for protection; a formation service can handle the paperwork so you can ensure your business receives all the tax benefits that come with it.

Utilize Self-Care Tactics

Once realistic goals have been established, utilizing various self-care strategies is crucial in avoiding burnout while taking care of someone with special needs. Try mindfulness practices like yoga or meditation, spending quality time with friends or family members, taking regular breaks throughout the day, getting enough sleep each night, and engaging in leisure activities that bring joy. These strategies allow individuals caring for someone who is on the autism spectrum time away from their responsibilities while still feeling capable and productive enough themselves.

Take Care of Your Body

When you care for someone else, it is easy to put your own needs lower on the priority list. But that is a big mistake. When you don’t care for your body, you actually become more tired and unmotivated. Instead, take steps to treat your body like it deserves to be treated. Fill your kitchen with healthy snacks, like fruits and nuts, that you can grab instead of something sugar-laden. And make an effort to park farther from your destinations so that you can get in a few more steps. You’ll find yourself feeling better physically and mentally more quickly than you might expect.

These practices will also help your little one to see what it looks like to be healthy. If you struggle getting your child to eat healthy foods, modeling is one great way to help change their perspective on those foods. You can also reach out to Feeding Matters, especially if you feel that your child may have pediatric feeding disorder. They have resources to help you help your child with their eating habits.

Ask For Help When You Need It

Although creating an effective self-care plan is essential when caring for a child with disabilities, it’s also important to seek professional assistance when needed so that burnout doesn’t take over entirely. There are counselors available both online and offline who specialize in helping individuals cope with life transitions associated with taking care of someone who has special needs. Additionally, there may be local support groups available where caregivers can come together and share stories and experiences, and this can help you figure out a care plan.

Consider Everyone’s Needs and Make a Plan

Creating an effective self-care plan as a caregiver for a child with disabilities can take some time, as you’ll need to constantly assess what works and what doesn’t. Consider keeping a journal that will help you vent your frustrations, and look for online resources that will assist with goals like starting an LLC or finding a new job. Try to be patient as you get started and know that once you begin to find strategies that work, the pieces will fall into place.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are solely those of the author who submitted it and do not necessarily reflect the views of Feeding Matters. We do not endorse any products or services mentioned in the post, and we are not responsible for any errors or omissions in the content. The information in this post is provided for educational and informational purposes only, and should not be considered as a substitute for professional advice.

Accurately Diagnosing PFD and ARFID: Why Misdiagnosis Can Do More Harm Than Good

Published by Jaclyn Pederson, MHI on Apr 21, 2023

I recently heard about a distraught mother of an eight-year-old, whose daughter spent time in an eating disorder clinic. She was diagnosed with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), which is often described as extreme picky eating.

After completing the program, her child showed no improvement and even developed more anxiety around eating. Minutes into the conversation, it was clear that this child most likely had undiagnosed pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). An effective assessment and treatment plan must address more than psychiatric and behavior therapy for any child who has been identified as having concerns with feeding.

As CEO of Feeding Matters, I hear these stories regularly.

In the two years since PFD became an official ICD diagnostic code, I’ve seen hundreds of families in the U.S. and around the globe become more informed and able to access better care for their children. Naming the issue that has many symptoms and requires a multidisciplinary approach has given families tremendous relief and support.

But, our work is far from over.

What happens when PFD is mistaken for an eating disorder

Children as young as one are being diagnosed with ARFID when they actually have PFD. In plain terms, this means children with a medical and multidisciplinary feeding disorder are instead diagnosed as having a psychiatric condition.

The actual cause of children’s limited intake or picky eating is sometimes overlooked. It’s nearly impossible to resolve a mental or behavioral eating issue without first looking into the other domains that contribute to eating function, including medical and feeding skills.

I’ve seen with my infant how eating is a learned behavior. My baby has a cow’s milk protein allergy and challenges with his suck and anatomy. Once we identified his issues, we switched formulas and found a better bottle for his anatomy. Even then, it still took a month for him to develop the necessary feeding skills to consume greater than one ounce per feeding. My child only had a feeding challenge, and was not diagnosed with PFD. Still, this shows how a holistic assessment and treatment plan that considers the interplay of the four domains of PFD allows for targeted interventions that match each child’s unique needs. With early identification and treatment of medical and feeding skill dysfunction, the hope is that the long term psychosocial impact can be reduced.

The longer feeding challenges go untreated, the greater the psycho-social impact. As children get older, psychological difficulties become the primary drive for feeding dysfunction and the problem evolves from a developmental one to a mental health condition.

Why PFD is often misdiagnosed as ARFID

ARFID is a mental health diagnosis for children who have the following:

- Significant weight loss (or failure to achieve expected weight gain or faltering growth)

- Marked interference with psychosocial functioning

- Nutritional risk or deficiency

- No coincident body image problems

- Disturbance is not due to a medical condition

PFD is a multidisciplinary diagnosis that includes feeding dysfunction in any one or several of four domains:

- Medical

- Nutrition

- Feeding skill

- Psychosocial

There are many reasons PFD is mistaken for ARFID. The main reason is that PFD is a much newer and less widely-known diagnosis. We facilitated the publication of a paper that provided a consensus framework of PFD in 2019. PFD became an ICD code in the U.S. in 2021, over a decade after ARFID. PFD has an international impact because the diagnosis was centered around the international classification of functional disability and health. The PFD diagnosis and subsequent ICD code use the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework. This framework allows the international medical community to evaluate the functional impact feeding has on a child’s activities. It also promotes a multidisciplinary, holistic assessment of how the four domains, medical, nutrition, feeding skill, and psychosocial, interconnect. This ensures the root cause of a child’s feeding challenges are identified.

However, psychologists and practitioners in the eating disorder world tend to know only about ARFID.

Information available on social media is another reason PFD is misdiagnosed as ARFID. Parents concerned about a child’s picky eating can go down a rabbit hole of online information that’s more likely to point to ARFID as online it gets inaccurately labeled as “severe picky eating.” The unfortunate piece to this is that in these conversations about ARFID and severe picky eating, social media presents a misleading picture that fails to take into consideration the medical or feeding skill reasons why a child might have trouble feeding.

Understanding PFD and ARFID

PFD and ARFID in children and young adults share symptoms and behaviors. The child does not eat as much or in a manner expected for a child’s age. The cause and the treatment for this behavior is what varies. Some children with PFD go on to develop ARFID.

A classic case of ARFID is someone with no history of feeding problems before its onset. For example, a child has a choking incident and then is afraid to eat. Another example would be a child with no feeding skills issues but is described as having odd eating habits.

A child with undiagnosed PFD will have a history of feeding issues. These can include any combination of issues, including: allergies, reflux, challenges with bottle feeding, and trouble transitioning to solids.

Treatment for a feeding disorder differs from an eating disorder. For PFD, a clinician will determine if the child is safe to eat. Does he have the skills to chew and swallow? Are there allergies that may be present?

When a child is treated only for ARFID, they’re entering a mental health pathway that can often be difficult to assess and identify if there are other domains present.

Education is vital to improve diagnoses of PFD and ARFID

Education is the key to providing better treatment for children with PFD and ARFID.

We at Feeding Matters are working with clinical experts in the field to help clarify how to determine the correct diagnosis and treatment plan for those who have either PFD or ARFID – or both.

Our goal is that clinicians will better understand both diagnoses so that more patients can be identified earlier and access effective treatment.

Parents need to be aware that PFD can sometimes be misdiagnosed as ARFID or that if PFD goes undiagnosed it can become a more severe ARFID. This knowledge will help more families get treatment from clinicians who understand how to treat PFD and how the two diagnoses overlap.

The earlier we help more families identify the true issue, the more likely we will ensure they get the help they need.

Are you looking for more information? Visit Feeding Matters’ resource page: PFD and ARFID.

Pass on the peas; pass the pizza, please

Published by By Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES on Mar 24, 2023

Is your child getting enough nutritional variety? How to know and what to do about it

By Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES

Mass General for Children Pediatric Nutrition Center of Excellence, Center for Feeding and Nutrition

Nutritional variety for children ages 0-5 is extremely important to the growth and development that happens in those early years. That said, it’s normal for young children – especially toddlers – to go through phases of picky eating as they explore their world and assert their independence. In honor of National Nutrition Month this March, read the blog below from expert pediatric dietitian Simona Lourakas of Mass General Hospital for Children to know what to expect when feeding young children and how to ensure they get the nutritional variety they need.

When your baby starts eating solid foods, it’s not uncommon to expect that transition to go well. No matter that the foods are only as exciting as room temperature, smashed peas. Other tots the same age are happily gumming blended foods.

But, as hard as you try, your child refuses to eat many of the foods you offer. Is this a sign of age-appropriate picky eating? Or is it an indicator of a more significant issue?

What is nutrition variety?

Nutritional variety for adults and children means eating foods from all food groups: grains, proteins, dairy, fruit and veggies. There are other calcium fortified foods for those who can’t eat dairy. And many fruits and veggies have a lot of nutrition overlap.

Exposing kids to solids builds up their feeding and oral motor skills. It helps prevent food allergies later on and increases diversity in the gut. For breastfed infants, iron-rich proteins can be an important food group such as iron fortified cereals, beans, leafy vegetables and lean meats.

At around nine months old, a limited variety or quantity of solids will start to impact growth, nutrition and oral-motor skills.

Why nutrition is so crucial for young children ages 0-5

Nutritional variety is critical, affecting every area of children’s growth and development. A study conducted by Feeding America shows that malnourished children:

- Cannot learn as much, as fast, or as well as peers

- Have more social and behavioral problems because they feel bad and have less energy

- Require frequent doctors’ visits

- Are at risk for cognitive development during this critical period of rapid brain growth

The kinds of nutrition, care, stimulation and love children receive during these critical first years of life determine the brain’s architecture and central nervous system. Identifying and treating feeding and nutrition problems are crucial to supporting children’s cognitive, physical, emotional and social development, as well as the caregiver-child relationship.

How to know if your kid is getting enough nutritional variety

Like anything in parenting, there’s a lot of pressure to compare your child’s eating to peers, especially once children enter daycare or preschool. This only adds to the stress parents can already feel around feeding their children and ensuring they get the nutritional variety they need.

Considering the size of your hand to your child’s hand is a good reminder of how small a child’s portions need to be. A portion of protein is only about the size of the child’s palm. A grain serving is the size of a closed fist.

Most children will not eat all five food groups in a meal and maybe not even in a day. Instead, consider what your child eats over the week. They’re likely getting enough nutritional variety if they eat foods from all food groups over that period.

What to do if you’re concerned

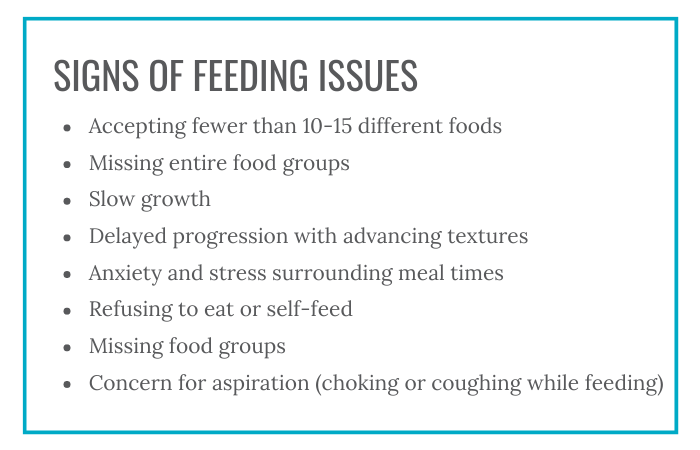

Developing a healthy eater is challenging for many parents. Even for children without any feeding issues, this can take time, patience and persistence. Children with food allergies, autism, sensory concerns, premature birth or medical complications will need a more specialized approach to eating.

Following are some signs of feeding issues:

- Accepting fewer than 10-15 different foods

- Missing entire food groups

- Slow growth

- Delayed progression with advancing textures

- Anxiety and stress surrounding meal times

- Refusing to eat or self-feed

- Missing food groups

- Concern for aspiration (choking or coughing while feeding)

Speak to your pediatrician if you are concerned about your child’s eating or nutritional variety.

Tips for parents to add nutritional variety to kids’ diets

1. Know that picky eating is normal for toddlers.

It’s normal for toddlers to have food preferences, such as more fruits vs. vegetables, grains and dairy.

2. Consider adding fortified foods or nutritional supplements.

For children who can’t have dairy, some fortified pea or soy milks are a suitable replacement. For children who are missing other food groups, fortified foods like cereals or supplements, like an age-appropriate multivitamin or formula, can make up for some of that missing nutritional variety.

3. Introducing new foods takes time.

It can take offering a food 10 or more times before a child will accept it. Add new foods with nutritional variety together with familiar foods. This will reduce the pressure or forcing your child might feel.

3. Involve your child. Children of all ages can help prepare and choose foods in safe, age-appropriate ways.

4. Allow children to play with new foods.

Food play is a great way to introduce new tastes and textures without making children feel pressured to try it. Some of the new food will often end up in young children’s mouths this way.

5. Avoiding grazing.

After one year, aim for three meals a day, with 1-2 snacks. Offer appropriate amounts of milk. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests 16-24 ounces per day of whole cow’s milk for 1-2 years and 16 ounces per day of low fat milk children 2+ years. Avoid juice. Grazing all day affects appetite at meal times.

Parents are doing their best

When it comes to feeding your child, know that how much your child eats doesn’t define how well you’re parenting. A parent’s job is to provide food and age-appropriate nutritional variety. It’s the child’s job to eat it.

Parents who offer food in the same way to siblings may find that one has feeding difficulties while the others don’t. As hard as it is to keep from comparing children to peers, including siblings, know that feeding issues are complex.

If you’re concerned about your child’s feeding, know you are not alone. Early detection and treatment of pediatric feeding disorder is critical to affected children’s long-term health and well-being. Check out our six-question screening tool on our website and reach out if you need more support.

Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES is a registered dietitian in Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition at Mass General for Children, a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. She also works with post-acute care rehab Franciscan Children’s.

Picky Eating: Just a phase or cause for greater concern?

Published by Cuyler Romeo, M.O.T., OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC on Jan 30, 2023

How to know if your child will outgrow picky eating. Plus, how to survive mealtimes with the pickiest palates.

From birth, the majority of time you spend with your infants and young children revolves around food. Children eat a minimum of six times a day. It takes hours to prepare food, feed kids and clean up.

This means that when feeding becomes a challenge, parents can feel like a failure. That was the case for Natalie Peterson, mom of Easton.

When Natalie introduced Easton to solid foods at 4.5 months, she immediately knew something was off. “How he reacted felt different. I brushed it off initially but I think deep down in my gut, that mom instinct knew something was different.”

They tried again and ran into that same reaction. Easton pushed the food away, refused it and even became angry. “It was incredibly isolating. It felt like we had failed him.”

Easton was the first child in the U.S. to be diagnosed with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD).

And Natalie certainly wasn’t the only parent to feel anxiety, frustration and shame over picky eating.

How common is picky eating?

Picky eating is a common disorder during childhood. According to Dr. Kay Toomey, pediatric psychologist and member of Feeding Matters, a variety of studies across the world suggest that approximately one-fourth to one-third of children on average will struggle with some type of feeding and/or growth issue in their first decade.

Picky eating can look similar, but the causes vary. Many toddlers experience a phase of picky eating when they need fewer calories than during months when they were growing faster. That decrease in appetite coupled with their curiosity about boundaries can lead to fussy eating.

It’s when this persists or becomes more extreme that picky eating could be a sign of another underlying condition, such as pediatric feeding disorder (PFD).

What is considered picky eating?

According to Dr. Toomey, the operational definition of picky eating is children who demonstrate either transient or more extended challenges (up to 2 years duration). She outlined the following feeding and eating patterns in a presentation for Feeding Matters:

- Strong preferences

- Limited variety

- A restricted number of foods they will eat.

- Avoiding new foods

- Refusing the “right” foods or the “right” amounts

- Getting more upset than peers

- Requiring a special meal by their parents

- May eat differently in different contexts

How can I help my child with picky eating?

While many children will be picky eaters in spite of parents’ best efforts, there are a few ways to encourage children to eat better.

Following are a few ideas you can try if you’re experiencing stressful mealtimes:

Establish a mealtime routine. Children find comfort and confidence in a predictable routine. This will depend on the needs of your family. There’s no right answer.

Set up loving, appropriate boundaries. I don’t expect a toddler to stay seated at the table for 30 minutes, but I would expect a two year old to eat at the table for 10 minutes instead of taking a bite from the table and running around. If your child is on the autism spectrum, this may not be an appropriate expectation.

Harness the power of hunger. You’re more likely to have successful mealtimes if your kids come to the table hungry. Having a predictable schedule will help.

Make meal time social. Eating with your child, enjoying foods together and modeling appropriate mealtime behavior can help.

Limit the introduction to new foods. New foods are an important way to teach your child about healthy eating. Introduce something new together with something familiar to help your child acclimate.

How long does picky eating last?

Among children who are picky eaters, only about one-third to one-half will outgrow their picky eating within two to three years. Three to 10 percent of infants and children have significant, persistent feeding and/or growth problems over time. These are the children who have pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) and need feeding treatment.

When should I be worried about picky eating?

While picky eating is a common behavior among children, extreme picky eating can lead to nutrient deficiencies or poor growth.

Extreme picky eating is a sign of PFD if a child displays some of the following characteristics:

- Extreme food selectivity: based on texture, color and taste

- Food refusal: gagging, vomiting, hitting, crying

- Limited appetite

- Poor weight or failure to gain weight

- Delayed or dysfunctional eating skills

- Disruptive mealtime behavior

- Eats differently in different environments

- Negatively impacts family functioning

Children with PFD need medical intervention to manage the diagnosis. When a child isn’t eating or drinking the quantity or the variety they need to grow and be healthy, it’s not just because they are being “fussy.” There is usually an underlying reason. Talk to your pediatrician about PFD and check out our family roadmap for support.

Cuyler Romeo is director of strategic initiatives at Feeding Matters and a clinician at Banner-University Medical Center’s NICU.