Nutrition education in schools: A teacher’s reflections

Published by Gabi Lake on Mar 21, 2024

Recently, I heard first-hand from a PFD Parent about how challenging it is to navigate feeding differences within the school system. She shared that her child came home saying that a friend had said, “Your lunch is not healthy,” in reflection of the school’s teachings around nutrition. Due to her daughter’s restrictive diet, this comment became detrimental to the child.

Teaching nutrition in school

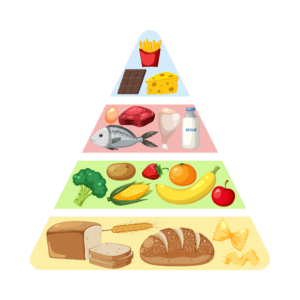

I spent eight years in the classroom, and every year our established curriculum had a unit on nutrition. We’d be instructed to teach about the primary food groups and the “My Plate” template that shares how to diversify your diet and eat all the food groups within a meal. Not only this, our cafeteria walls were also lined year-round with similar concepts and “clever” taglines like: “Fruits & Veggies Make Your Plate Great!”

I never really thought much about how this could be harmful, and how, without even trying, these concepts might traumatize some of my students with pediatric feeding disorder.

When you do not struggle to eat – whether that be in one domain or all four – it is easy to say, “Yes, you need to eat protein, grains, fruit, vegetable, dairy at every meal.” But for someone who might only consume four foods total – that is not only unrealistic, but unempathetic towards their lived experience.

“Build a Meal” lesson with PFD

One year, I taught a lesson that required each student to search through magazines and “build a meal” by cutting out foods, as applicable to the “My Plate” portions.

One of my students with PFD started off okay. He found apples first (one of his safe foods) and pasted it to the “FRUIT” section of his plate; he found popcorn and pasted it to the “GRAIN” section. Easy, simple, fun. Then came the other three – protein, dairy, and his least favorite of all, vegetables.

Knowing that he would struggle with finding items, I sat with him through this activity as we flipped through the magazines together. Any time I saw a vegetable, I said, “Hey, what about a carrot? Is that a vegetable?” His whole body said “No,” but his mouth said, “Yes.” I watched as he visibly held back his nausea and grabbed the magazine with his index finger and thumb as if it were a smelly shoe.

“It’s okay, we don’t have to put a carrot… let’s keep looking!” I told him, seeing he was clearly uncomfortable. Through every one – gagging, just at the sight/thought of these foods being on his plate. Same with the protein, same with the dairy.

We finally landed on pizza. I said, “Hey, I’ve seen pizza in your lunchbox! That has grains, protein, AND dairy!” We talked through how cheese and dough provide nutrients to our body; I even wound up counting the tomato sauce as a vegetable. With his apple, popcorn and pizza, we agreed that he had met all his food groups. He seemed content with that, especially since it meant he didn’t have to keep looking at pictures of so many wretched foods.

He didn’t leave the activity in tears or distress, but he may have left with the thought that his safe foods weren’t safe or good enough. When, in fact, those foods are keeping him safe.

Approaching nutrition

In reflection and with a growth mindset, I’d like to offer these thoughts:

- What is healthy or nutritious may vary. We must be accommodating and approach foods neutrally to provide equitable support to children who have feeding differences.

- While there’s nothing wrong with encouraging a diverse diet, that should not be the be-all, end-all goal. The goal should be listening to your body and learning to work with it rather than against it. We should be guiding children toward practical tools to develop a positive and safe relationship with food.

So how can we nurture this mindset and as well as our children?

- We should be consulting children and their families on what would help them and develop the curriculum with unique needs in mind.

- We should be working collectively as a society to eradicate diet culture. When all food is neutral, when all body types are acceptable, when support needs are normalized, and accessibility tools are widely-available – these concepts will no longer have a place in the world.

As I reflect on my own journey with food and diet culture, and as I learn and grow to understand PFD more clearly, I truly feel that equitable nutrition is possible and will create a world where children with pediatric feeding disorder thrive.

Gabi Lake is the administrative assistant at Feeding Matters, and was also a special education teacher in the public school system.