Premature births on the rise, leading to more pediatric feeding disorders

Published by Feeding Matters on Jan 24, 2023

Here’s what you need to know about the stats on premature births in the U.S., its causes and what we can do about it.

For most families of babies in the NICU, a premature birth comes as a total surprise. That’s because nearly 90 percent of babies in the U.S. are born at gestation, after 37 weeks. But an increasing number of newborns are born prematurely, according to the March of Dimes 2022 Report Card, released in November.

A rising rate of premature births results in an increasing number of babies with feeding issues. Those children who develop long-term feeding issues are at risk of having a pediatric feeding disorder, or PFD.

With a rate of 10.4-10.7 percent of babies born prior to 37 weeks in the U.S. in 2021, the March of Dimes gave an abysmal preterm birth grade of D+. It’s a rate that’s .4 percent higher than the previous year and the highest recorded rate since 2007.

Globally, the rate of preterm birth ranges from 5 to 18 percent of babies born, according to the W.H.O.

The number of weeks babies are born prior to full term and the newborn’s health will determine how long families spend waiting for their babies’ release from the NICU. In an average week in the U.S., nearly 70,000 babies are born. Over 7,000 of them are premature.

Depending on how premature a baby is and problems that may have occurred during their stay in the NICU, most of those babies eventually go on to reach all the milestones of their full-term peers. But this unexpected start is distressing for parents. The biggest challenge for most of the babies is feeding.

NICU staff spend most of their time supporting preterm babies’ nutrition needs, says Dr. Matt Abrams, a neonatologist with Arizona Neonatology at HonorHealth Scottsdale Shea Medical Center. “Feeding difficulty is one of the most common and challenging things we deal with in the NICU. Although people think of preterm babies as having breathing issues, most of the time in the NICU, we spend on nutrition and transitioning to oral feedings.”

The duration of a preemie’s feeding challenges is inversely related to their gestational age. The more pre-term the baby, the more likely they are to take longer to mature. Upon release from the NICU, Dr. Abrams says most of these babies will start to eat normally after a few weeks at home. But some of them will continue to struggle with feeding challenges.

The annual prevalence of PFD in the United States is between 1:23 and 1:37 children under the age of 5. This is higher than other more well-known childhood conditions such as autism (1:54) and cerebral palsy (1:323). Not all children diagnosed with PFD were once preemies, but many of them were.

Causes of preterm births in the U.S.

There are several variables that determine whether or not a baby is born prematurely. These include the following:

- The age and health of the mother

- Contraction of COVID-19 while pregnant

- Obesity and hypertension

- Multiple gestation

- Proximity to a hospital

- Race

- Poverty

- Access to prenatal care

- Smoking/drinking/drug use

Among other contributing factors such as access to prenatal care, Dr. Abrams sees fertility treatment as a key reason for more premature births. “Some places are not being judicious about how many embryos they’re implanting, which leads to higher rates of multiple gestations and therefore increases risk of premature birth,” says Dr. Abrams.

Whatever the cause, an early delivery is a challenge and a shock for parents. This was the case for Paula Benzing, a mom of three in Mesa, Arizona.

Paula visited her doctor for stomach pain, indigestion and heartburn. These symptoms are common in pregnancy, but Paula’s case was severe. Her doctor ordered blood work, and she was diagnosed with HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count.

Paula had a cesarean section right away, at 28 weeks. Her son, Isaac, who’s now 13, was in the NICU for 3.5 months. Much of that time, and for months afterward, was spent on feeding therapy and bottle therapy.

Paula’s second child was born at term. With her third, 6-year-old Penny, Paula once again had to deliver at 28 weeks. Penny needed even more feeding support than Isaac. She came home from the NICU with a feeding tube, which was replaced by a g-tube at six months.

Paula’s day revolved around feeding Penny, all while chasing a two-year-old toddler. Every three hours she’d thicken formula to attempt to feed Penny orally – knowing she wasn’t likely to take it. She’d toss out that formula and instead mix a thinner version for the g-tube instead. “No matter how slow we did it, most of the time she’d throw up. I was a big ball of stress,” says Paula.

Dr. Abrams sees countless anxious parents in the NICU who stress over their babies’ feeding progress. “Eating is social, so it’s very distressing to families when kids can’t do that. At the same time, it’s not very tangible. When babies are on a ventilator or they have something more concrete, families cope much better than when their baby is totally healthy but having feeding issues. They must be patient to see how things evolve over time.”

The increase in preterm births in the U.S. means more and more families are having to be patient. But, not all families are affected equally.

Race and geography matter for maternal health

In the March of Dimes report card, some states scored worse than others. Nine states and one territory, including seven states in the Southeastern United States, received a grade of F. Only one state, Vermont, received a A- state-level preterm birth rate, with the lowest preterm birth rate at 8 percent.

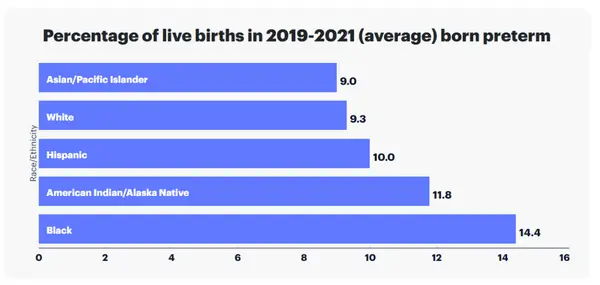

Preterm birth rate also varied by race and ethnicity in the United States. Preterm birth rate among Black women is 52 percent higher than the rate among all other women, according to the report.

Within states, the likelihood of preterm birth varies as well, depending on location, economics and ethnicity.

Impact preterm birth has on children and families

A preterm birth is often stressful for parents during their baby’s stay in the NICU. Juggling work and home responsibilities compounds that anxiety. Preemies are typically sent home with overwhelming and time consuming care instructions that can include multiple care appointments.

Parents of children who require longer support or have additional diagnosis, like pediatric feeding disorder, carry an even heavier burden.

According to a nationwide survey of insured families conducted by Feeding Matters:

- 76% of respondents reported that PFD results in at least a moderate financial burden for their family

- 33% of respondents had to leave full-time employment

- 23% turned down a job offer/raise in pay/more hours per week

- 47% reported depression

Overall, the lifetime average income loss to a family is $125,645.

The stress for a family can be tremendous for the duration of a child’s feeding challenges. Denise Hoffman is a pediatric occupational therapist and clinical assistant professor at Indiana University South Bend. While she was uniquely positioned to support her child who was born prematurely and had feeding issues, she still faced massive challenges. She had the luxury of quitting her job and made breastfeeding her son, Trey, a full time job. She describes feeding him and practicing feeding therapy a 24/7 job. Still, she recalls that he’d only manage to eat an ounce in a feeding.

Besides the time commitment this requires, the stress takes its toll. “As a mother your instinct is to feed your kid, and when you can’t, you feel like a failure,” she says.

Denise was grateful that she could stay home with her son and his older brother. She also had help from family. Many Americans facing similar struggles aren’t as fortunate.

How the U.S. can decrease the rate of preterm births

Prenatal care helps prevent preterm births. But Dr. Matt Abrams argues intervention needs to take place even before pregnancy.

“I think the work must be done before pregnancy by reducing complications related to obesity, diabetes and hypertension and by having fertility treatment that is judicious about who is a good candidate and how many embryos are implanted. Once you’re pregnant, there are few ways to reduce preterm birth other than good prenatal care. In rural areas of the country, it means increasing access to telemedicine.”

The March of Dimes advocates for much-needed legislation and funding that can improve maternal and infant health outcomes. Click here to read about their campaign #BlanketforChange to advocate for health equity for moms and babies.

They say it takes a village to raise a child. Turns out, it takes the will of a whole country to support newborns and their families.

Feeding Matters is the first organization in the world uniting families, healthcare professionals, and the broader community to improve the system of care for children with pediatric feeding disorder through advocacy, education, support, and research.