Category: Nutrition

Nutrition education in schools: A teacher’s reflections

Published by Gabi Lake on Mar 21, 2024

Recently, I heard first-hand from a PFD Parent about how challenging it is to navigate feeding differences within the school system. She shared that her child came home saying that a friend had said, “Your lunch is not healthy,” in reflection of the school’s teachings around nutrition. Due to her daughter’s restrictive diet, this comment became detrimental to the child.

Teaching nutrition in school

I spent eight years in the classroom, and every year our established curriculum had a unit on nutrition. We’d be instructed to teach about the primary food groups and the “My Plate” template that shares how to diversify your diet and eat all the food groups within a meal. Not only this, our cafeteria walls were also lined year-round with similar concepts and “clever” taglines like: “Fruits & Veggies Make Your Plate Great!”

I never really thought much about how this could be harmful, and how, without even trying, these concepts might traumatize some of my students with pediatric feeding disorder.

When you do not struggle to eat – whether that be in one domain or all four – it is easy to say, “Yes, you need to eat protein, grains, fruit, vegetable, dairy at every meal.” But for someone who might only consume four foods total – that is not only unrealistic, but unempathetic towards their lived experience.

“Build a Meal” lesson with PFD

One year, I taught a lesson that required each student to search through magazines and “build a meal” by cutting out foods, as applicable to the “My Plate” portions.

One of my students with PFD started off okay. He found apples first (one of his safe foods) and pasted it to the “FRUIT” section of his plate; he found popcorn and pasted it to the “GRAIN” section. Easy, simple, fun. Then came the other three – protein, dairy, and his least favorite of all, vegetables.

Knowing that he would struggle with finding items, I sat with him through this activity as we flipped through the magazines together. Any time I saw a vegetable, I said, “Hey, what about a carrot? Is that a vegetable?” His whole body said “No,” but his mouth said, “Yes.” I watched as he visibly held back his nausea and grabbed the magazine with his index finger and thumb as if it were a smelly shoe.

“It’s okay, we don’t have to put a carrot… let’s keep looking!” I told him, seeing he was clearly uncomfortable. Through every one – gagging, just at the sight/thought of these foods being on his plate. Same with the protein, same with the dairy.

We finally landed on pizza. I said, “Hey, I’ve seen pizza in your lunchbox! That has grains, protein, AND dairy!” We talked through how cheese and dough provide nutrients to our body; I even wound up counting the tomato sauce as a vegetable. With his apple, popcorn and pizza, we agreed that he had met all his food groups. He seemed content with that, especially since it meant he didn’t have to keep looking at pictures of so many wretched foods.

He didn’t leave the activity in tears or distress, but he may have left with the thought that his safe foods weren’t safe or good enough. When, in fact, those foods are keeping him safe.

Approaching nutrition

In reflection and with a growth mindset, I’d like to offer these thoughts:

- What is healthy or nutritious may vary. We must be accommodating and approach foods neutrally to provide equitable support to children who have feeding differences.

- While there’s nothing wrong with encouraging a diverse diet, that should not be the be-all, end-all goal. The goal should be listening to your body and learning to work with it rather than against it. We should be guiding children toward practical tools to develop a positive and safe relationship with food.

So how can we nurture this mindset and as well as our children?

- We should be consulting children and their families on what would help them and develop the curriculum with unique needs in mind.

- We should be working collectively as a society to eradicate diet culture. When all food is neutral, when all body types are acceptable, when support needs are normalized, and accessibility tools are widely-available – these concepts will no longer have a place in the world.

As I reflect on my own journey with food and diet culture, and as I learn and grow to understand PFD more clearly, I truly feel that equitable nutrition is possible and will create a world where children with pediatric feeding disorder thrive.

Gabi Lake is the administrative assistant at Feeding Matters, and was also a special education teacher in the public school system.

Budget-friendly bites: Navigating picky eating challenges in less time

Published by Courtney Bliss on Mar 19, 2024

When parenting a picky eater, we have to discard much of what we learn about food as adults. Diet recommendations to eat a lot of protein, avoid carbs and stay away from fat don’t translate well to kids’ diets –– especially to one who only eats a limited number of foods.

Good nutrition for children and adults involves a combination of different food groups over a week. The quality of that combination is known as the Healthy Eating Index, the gold standard for assessing nutrition.

Each macronutrient fuels the body differently. Some supply quick bursts of energy and others offer steady energy release.

This is why teaching kiddos to listen to their body signals is important. Intuitive eating means paying attention to hunger and fullness cues. This can be particularly challenging for children with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) because the anxiety of eating can mask hunger cues.

In some cases, the way we label food and the shame around it can make kids’ feeding worse. For picky eaters, worry less about food labels and instead focus on what nutrients are being delivered to your child’s body.

For example, here are some ways to reframe thinking around some typical foods for picky eaters:

- If your child only eats chicken nuggets, consider this a consistent protein and fat source that provides more steady energy.

- If your child only eats air-fried snap peas, this may not be fresh produce, but they’re still full of nutrients, fiber, protein and fat.

4 food categories kids need

There are four different macronutrients our bodies use. Each works a little differently.

Carbohydrates: Our bodies use carbohydrates quickly. They cause glucose to rise and enter the bloodstream faster.

Examples: Bread, crackers, pasta, cookies and cakes.

Fiber: This is technically part of the carbohydrate family, but our bodies don’t use it immediately for energy. Instead, our bodies use it to help food move slower through the bloodstream. They help with digestion and also make our energy last longer.

Examples: Fruits, snap peas, carrots, nuts, beans and whole grains.

Protein: Kids don’t require as much protein as adults. But, incorporating protein-rich foods into meals and snacks can help keep kids feeling full longer. To know how much your kiddo needs, consider protein intake over a week rather than obsessing over individual meals.

Examples: Chicken, fish, eggs, dairy, beans, nuts, nut butter and seeds.

Fat: This is the nutrient families skip the most, especially from parents raised in the 1980s and 1990s when fat was demonized. Fat is a core component to building hormones our bodies need. It releases energy slowly and keeps kids feeling full longer.

We need fat. Your kid needs fat. It’s building their brains and spinal cord. Don’t skip it.

Example: Peanut butter, cheese, avocado and foods cooked in olive oil.

How much of each nutrient your kiddo needs is super personalized. What’s true for everyone is that adding other nutrients to carbohydrates makes energy release longer. (Read: your kids won’t be asking you for snacks every five minutes!)

How to incorporate more healthy nutrition into your picky eater’s diet

In my years helping families of picky eaters, I have seen two common approaches to family meals:

- Those who serve family meals and accept that their child may or may not eat it.

- Those who make a completely separate meal.

If your goal is to get your kiddo to eat more variety and join the family dinner, taking a step back to plan can help you incorporate more of the true variety your kid will eat.

Following are five tips for families of picky eaters.

- Create a meal schedule.

- Combine nutrients for snacks and meals.

Each nutrient provides our body with energy in different ways. Combining foods helps your kiddo feel full longer. For example, eating a carb like a few graham crackers will give a quick burst of energy, but it won’t last. Adding peanut butter and apple slices to a graham cracker combines nutrients to provide a more filling snack. Pairing applesauce with some chips will keep your child full longer than just eating one macronutrient at a time. Eating this way doesn’t honor how the body metabolizes food and instead leans into fast energy releases.

Try to avoid: Providing free access to snacks, like applesauce pouches or a bag of chips, that are more likely to encourage grazing than satiety. - Look for brands with more balanced nutrition labels.

If your child is not particular about the brand you buy, you’ll find that some will have more fiber or protein than others. For example, if there are different kinds of cheese crackers and a nutritional difference, buy the more filling option.

Try to avoid: Feeling guilty about a processed food label when it’s one of few your child eats. Instead, focus on what nutrients might be in it and choose the best option your child will accept. - Make a meal plan based on what your child will eat.

Consider what foods your child eats and then combine them with other nutrients. For example, if your child eats waffles and blueberries, serving them together provides more nutritional balance. Combining “safe” foods over the course of the week will mean your kiddo gets more servings of nutrients like fiber and protein.

- Add some of your child’s “safe” foods to family meals.

Adding foods to family meals that your child likes might make your picky eater more interested. Write out a list of what your kiddo will eat. Then think creatively about how to turn that into five dinners you can rinse and repeat each week. For example, your kiddo loves apples and eats them whenever they’re served. Add apples to the family dinner rotation by serving them on the side, and your child might join the family at the table.

When your child isn’t grazing all day, you allow their body time to digest foods and then get hungry again. The food we eat sends chemical triggers from the belly to the brain. The sensations of feeling full and hungry are often diminished in children who are picky eaters.

Try to avoid: Constant access to snacks. Little bites at a time can reinforce picky eating.

Over the years, I’ve seen even the pickiest eaters increase nutritional variety with time and support. Know that the way your child eats now is not forever. Working on providing different foods is enough.

Courtney Bliss is the owner of Feeding Bliss and is an experienced registered dietitian specializing in pediatrics.

Getting the most out of feeding therapy for PFD: A step-by-step guide to finding the right pediatric feeding therapist

Published by Nicole Williams, OTD-OTR-L, at Desert Valley Pediatric Therapy in Arizona on Feb 15, 2024

When your child needs feeding therapy for pediatric feeding disorder (PFD), navigating the system to access treatment can be challenging. If your pediatrician recommends feeding therapy, the following are some tips for how to find the right match.

Understand the role of feeding therapistsFeeding therapy requires additional training that neither pediatric speech and language pathologists (SLP) nor occupational therapists (OT) typically learn in graduate school. Look for a clinician who has obtained this additional training and has been mentored by another experienced feeding therapist.

Both SLPs and OTs can be qualified to provide feeding therapy. There are times when one discipline is better equipped to support your child than the other.

SLPs have extensive knowledge of swallowing, chewing and the oral motor part of feeding therapy. If your main concern for your child is choking or chewing, speech therapists are best equipped to help.

An OT is an expert in sensory issues and texture aversions. If the feeling of food in your child’s mouth, combining foods or picky eating are the issues, look for support from an OT.

Even in the initial feeding therapy evaluation, you might want to request one specialty over the other. If you’re unsure, let the intake team know your feeding concerns. They should be able to match you with the right therapist.

Check your insurance benefitsIn many cases when a child needs feeding therapy, the referring physician will not indicate whether the therapist should be an SLP or an OT. In some cases, though, your insurance will specify coverage for one or the other. It’s a good idea to understand your benefits before requesting a therapy intake evaluation.

Set expectations from the startTo get the most out of feeding therapy, share your goals from the start. Even during the initial evaluation, it’s important that you and your child’s therapist have aligned goals. For example, if your child responds to a specific approach or personality, be sure to share that. In many cases, therapists can adjust to match your child’s needs. Part of the therapeutic use of self is learning to gauge and meet children where they are.

Feeding therapists have to be flexible. This means goals should be fluid from the start. If your child isn’t reaching their therapy goals, it’s time to adjust them. If your child has a setback, like a hospitalization, you may need to change your goals entirely.

Find out how to be a partner at homeAs feeding therapists, we only have one hour a week to work with a child. That’s why we typically ask parents to join us during sessions so you can continue the therapy at home. As much as parents need breaks built into the schedule, therapy is not the ideal time.

Expect collaboration

Expect collaboration

From the start, feeding therapy is collaborative. During the initial evaluation, you’ll set goals and therapy expectations together with the therapist. You should also expect your therapist to work closely with any other clinicians who support your child.

Know that feeding therapy is not linearUnlike the progress you might see in speech therapy, for example, feeding therapy tends to progress at a slower pace. Overall, you’ll want to see an upward trajectory of progress in feeding therapy, but it’s normal for your child to have ups and downs. What you don’t want to see is a plateau over time.

Don’t be surprised if it takes time to see progress in feeding therapy. Some kids are slow to build rapport and feel comfortable with a therapist. If your therapist is answering your questions, being collaborative and is confident in their approach, be patient.

Don’t be afraid to pivot if it’s not working outIf you’re not seeing positive progress over time or if your child’s feeding therapist isn’t a good fit, be sure to raise these concerns. In many cases, the feeding therapist can make improvements.

If results don’t improve, your child may need support from another therapist. Try switching therapists to see how your child responds. If that doesn’t help, your child may need support from another discipline entirely –– such as a gastroenterologist or a psychologist.

Consider the following questions and answers for a potential feeding therapist:

Q: How long have you been seeing and treating children with pediatric feeding disorder? A: Look for someone with at least a few years of experience.

Q: Are you familiar with the Pediatric Feeding Disorder Consensus Definition and Conceptual Framework article published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition? A: If not, look for someone willing to read the article.

Q: Do you have specific education and training regarding pediatric feeding disorder? A: Look for someone who has additional training to understand the issues.

When therapists finish school, they usually don’t just jump into feeding therapy. Feeding is a specialty within speech therapy and occupational therapy that requires additional training and guidance under an experienced feeding therapist.

Q: Have you seen a child who’s had a similar experience?A: Finding a therapist familiar with your child’s specific feeding challenges is important. Don’t be afraid to ask this specifically to be sure you’re comfortable with the answer.

Q: Describe your overall approach to pediatric feeding disorder.A: Look for someone who understands the medical, nutrition, feeding skill and psychosocial domains and is willing to collaborate with a multidisciplinary team.

Q: How do you determine if a child is growing well? A: Look for someone who follows your child’s growth pattern, not just a standard growth chart.Q: How do you share the results of diagnostic testing, treatment goals, and other information with me and other providers treating my child? A: Look for a practitioner who partners with professionals in other disciplines and keeps open lines of communication with them as well as with you. Make sure they are willing to provide you with copies of reports and take the time to go over reports with you.

A story of triumph over pediatric feeding disorder

Published by Feeding Matters on

The way pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) manifests in each child is as varied as the children themselves. But so many stories of parenting children with PFD are the same.

An infant struggles to feed and gain weight. Parents work tirelessly to feed their children and juggle medical visits. They search in the dark for a diagnosis of a complex problem they don’t understand, all while feeling alone and at fault.

Raising a child with PFD is a journey that rarely has a final destination. With the right support and care, it does get easier. This is the story of one mom of a son with PFD and how she’s gone from seeking help to supporting others.

One family’s journey with PFD

From the start, Erin Avilez’s son, Julian, struggled to breastfeed and gain weight. Her doctors were concerned about her baby’s measurements throughout her pregnancy. When her amniotic sac fluid was low, Avilez was induced at 37 weeks.

Julian was born at 5 pounds and right away had trouble sucking and taking in enough food at each feeding. Avilez switched to bottles, but Julian continued to undereat. “Within the first few months, there were already red flags that he was underweight and not getting enough nutrition,” she says.

Avilez and her husband started by switching formulas to see if Julian had some sensitivity to some ingredients. Still, they didn’t see much weight increase. Things got worse when her pediatrician sent Julian to a pediatric gastroenterologist. “That’s kind of where the horror of the story started,” she says.

Julian’s pediatrician and the GI weren’t communicating or working together and sometimes had different goals. “The GI’s only goal was for Julian to gain weight and cared less about how it affected his feeding,” says Avilez.

Julian got a nasogastric tube (NG tube) at three months old. The increase in calories made him vomit a lot, and he regularly pulled the tube out. Any time he pulled the tube out, Avilez would have to call her husband to come home from work so the two of them could force the tube back in. Insurance only covered a few tubes, making this devastating ritual even more difficult. Julian developed an oral aversion that he never had before and wouldn’t even let his parents touch his face. By seven months, Avilez insisted the NG tube be removed.

When Julian’s GI recommended a gastrostomy feeding tube (G-tube) instead, Avilez knew they needed a second opinion. Julian took some formula and solid foods orally, and Avilez thought they could build on that. A new GI at Phoenix Children’s Hospital agreed.

With a new pediatrician and GI, Julian’s doctors started working on finding a diagnosis. He was also able to join their intensive feeding therapy program. “The new GI doctor we saw listened, and he offered empathy and support,” says Avilez.

When Julian was 3.5, his family finally got a diagnosis of what caused his pediatric feeding disorder. A liquid and a food study showed that he has gastroparesis, a condition where the stomach muscles do not work properly to empty waste.

Now that Julian has a diagnosis, he’s able to take medication to help his gastric delayed emptying, as well as an appetite stimulant. He also drinks Ensure Clear to add more calories to his diet. Julian has an aversion to any formula or dairy because of his early experience with the NG tube.

In the past six months, Julian was finally registered low on the weight chart for the first time. “This is huge for him,” says Avilez.

Still, says Avilez, their struggle is never far from her mind. She dreads visits to the pediatrician when she knows Julian will be weighed. “Even today, a week before his appointments, I start getting stressed out because I know we have to get on the scale,” she says.

Finding support from other families with PFD

Julian was born during the pandemic, and Avilez left her job as a social worker to take care of him and to get to all his appointments. She suffered from postpartum depression and felt overwhelmed, alone and isolated.

“I knew there has to be some type of service out there to help moms like me,” she says.

Avilez searched online and found Feeding Matters. She requested a peer-to-peer mentor and was matched with another mom who shared her experience. That empathy was powerful. “She listened to me. The first time I got off the phone with her, I started crying that somebody understood what I was going through,” says Avilez.

Avilez’s mentor also told her she was doing a great job. “Throughout this process, nobody told me I was doing a good job, not the doctors or anyone on his care team,” she says.

Avilez’s introduction to Feeding Matters was the first time she learned about PFD. “I felt so validated that we weren’t the only ones concerned about not knowing what was going on with our son and not hearing about it from our doctor,” she says.

Today, Avilez is a peer mentor to other parents raising a child with PFD. She’s grateful to have support and to be able to pay it forward. Her hope is that more clinicians and hospitals will inform parents about PFD from the start. “I wish that when you have a child with feeding difficulties, someone from the start would offer resources,” she says.

Key takeaways for supporting your child with PFD

Avilez offers the following advice to parents raising a child with PFD.

- Find a supportive care team: If the doctor’s not listening, find a more supportive provider. Having a good team in place makes all the difference.

- Trust your instincts: It’s okay to get a second opinion and ask questions. Keep advocating for your child because you know your child best.

- Find friends, family or a peer mentor: Find someone who will listen and understand so that you feel less alone.

Feeding questionnaire a springboard for physical therapy needs

Published by Karen Crilly, PT DPT, Advanced clinical specialist at Texas Children’s Hospital on Oct 20, 2023

How one physical therapist uses the Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire to identify a child’s areas of need and how she can help

Feeding challenges never occur in a vacuum. While I’m neither a speech therapist or a feeding therapist, the Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire® (ICFQ©) from Feeding Matters remains one of my most important assessment tools in my initial encounters with new patients.

The ICFQ was authored in partnership with internationally renowned thought leaders representing multiple disciplines related to feeding. It’s an age-specific tool designed to identify potential feeding concerns and facilitate discussion with all members of the child’s healthcare team – including physical therapists (PT).

Based on the caregivers’ responses to six questions, the ICFQ has been shown to accurately identify and differentiate pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) from picky eating in children 0-4.

Using the feeding questionnaire as a physical therapist

Whenever I meet with a new PT pediatric patient at Texas Children’s Hospital, I spend the first session speaking to the family to determine how we can help the whole child.

For example, I recently was working with a family in the plagiocephaly – head-shaping – clinic at Texas Children’s. When I asked the parent about feeding, she responded that the baby just won’t stay still to eat. That response led me to ask more questions about feeding. I learned the baby has torticollis – tightness of neck muscle that causes the baby to turn to one side. Plus, the baby was dysregulated, which could mean a neurological issue. I asked about reflux, which could be a gastrointestinal issue. I knew how to help in some areas as a PT, and I knew to refer the family to an occupational therapist and a speech pathologist.

I can’t even describe how relieved this parent was. When it came to feeding, everyone else had simply told her to “keep trying.”

While physical therapy focuses on a child’s functional mobility, no movement’s isolated from the rest of a child’s health. Movement takes mental and physical regulation. An infant requires proper nutrition to perform at their highest level. A child without enough calories doesn’t have the necessary energy to make the most progress in physical therapy – or any other therapy, for that matter.

6 feeding questions that help me identify physical therapy patients’ needs

There are six basic questions on the ICFQ that clinicians identify when a child has a feeding issue. As a physical therapist, responses to the questions highlight issues around endurance, function level and the parent’s understanding of the child’s needs.

Following are the six questions and how the responses help me as a physical therapist.

- Does your child let you know when he/she is hungry?

This question gives me insight into how well parents understand their child’s communication cues. Recognizing an infant’s or nonverbal child’s cues allows parents to know when a child is hungry, uncomfortable or tired. This communication is essential to the parent’s ability to do PT exercises at home.

- Do you think your baby/child eats enough?

Often, the responses to this question are cultural. Among the patients I see at Texas Children’s, I find some cultures expect babies and children to eat more than others. This is an opportunity to educate parents about what is typical. For those babies and children not getting enough nutrition, it’s a chance to refer them to specialists who can help.

- Do you have to do anything special to help your baby/child eat?

This question helps me gauge a baby’s stamina level. The baby may be having trouble coordinating breathing with swallowing. This tells me that in physical therapy, I need to work on the baby’s ability to open her chest out wide and back in. The goal is to increase the baby’s endurance to work for 30 minutes of exercise. That causes fatigue at the time, but it actually builds stamina for later.

A baby who doesn’t have the endurance to finish feeding isn’t likely to have the energy to make as much progress in physical therapy. This makes getting more calories into the baby especially relevant for PT.

- Do you have to do anything special to help your baby/child eat?

This question helps me determine when a baby is dysregulated. It means I need to refer to a specialist who can help the family uncover why feeding isn’t typical.

In physical therapy, I’ll determine whether the child needs to work on muscle retraction. This is one of the issues I see often in infants, especially, and sometimes even older children who are having trouble feeding. Retraction takes them away from their midline without being able to find their center again easily. This makes it difficult to eat.

As a physical therapist, I’ll work with the baby on midline rotation. We work on coordinating the movement of opening and closing the arms and chest. The baby’s shoulders should expand back and then be able to come back to center. The baby should be able to find his flexion and make symmetrical motions in the upper and lower body.

Working on the body in this way can improve feeding, supporting the therapy that speech pathologists and occupational therapists are doing as well.

- Does your baby/child let you know when he is full?

When a baby is not recognizing fullness, this indicates there might be a chronic condition. Once full, a baby should cry, turn the head, push away the breast or bottle or spit out milk. But if a baby just keeps eating, this is a cue that the family needs a referral to a specialist.

As a physical therapist, it helps me identify a baby’s level of function.

- Based on the questions above, do you have concerns about your baby/child’s feeding?

Responses to this final question provide an opportunity for education. I’ll know how much information I should give parents on typical development for their child’s age and stage.

It’s also an opportunity to encourage parents who need a referral to go ahead and make that appointment.

As physical therapists, we’re not just looking at the legs and the feet. Treating our patients means treating the whole patient.

Knowing how a child is feeding doesn’t only alert me to a patient’s nutrition needs. It helps me identify other issues a child might be experiencing. Each question in the ICFQ paints a picture of the whole child’s needs.

Karen Crilly, PT, DPT, MAPT, CBIS, is an advanced clinical specialist at Texas Children’s Hospital who has dedicated her professional life to forming a strong background and expertise in the assessment and treatment of infants and children with chronic and complex developmental and/or neuro-motor impairment.

Overturning insurance denials for PFD

Published by Feeding Matters on Sep 20, 2023

Navigating insurance coverage for pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) exacerbates the challenges of dealing with a complex medical diagnosis. The ICD-10 code that made PFD an official diagnosis meant getting the green light from insurance is significantly more straightforward today. But many families still face insurance denials.

Anyone who’s ever spent time on hold with an insurance call center or repeated a medical story multiple times to different agents knows how frustrating these calls are. Managing insurance bureaucracy while parenting a child with PFD is exhausting.

Stages of overwhelm are typical for families of children with PFD. Parents of young children in general are often sleep-deprived and stretched thin while balancing parenthood, work and life. Add multiple clinical appointments and round-the-clock feeding sessions to the mix, and it’s no wonder PFD parents are stressed.

How one mom overturned an insurance appeal to for an important treatment

Emily Adams, mother of 6-year-old Morgan and a long-time insurance insider with USI, shares how she battled insurance denials and offers tips for other families.

Morgan had severe reflux as a baby and only ate from a bottle in her sleep. Despite “dream-feeding” all night, she continued to lose weight. At 1.5 she got an NG tube to get the nutrition she needed.

Eventually, Morgan’s reflux improved with the proper medication. Emily then searched for a feeding program that would repair her toddler’s relationship with food. Finding the perfect program at Nationwide Children’s in Columbus, Ohio and securing a spot there was a feat of its own. Getting insurance to pay for it proved just as challenging.

Morgan at that point didn’t have an official diagnosis because the ICD 10 code was not yet established. Clinicians had to get creative with billing codes for Morgan’s therapy sessions. It wasn’t unusual for United Healthcare to deny them. That meant Emily was used to appealing denials by figuring out what code to use and then having Morgan’s clinicians resubmit them.

This came to a head one Monday morning when Emily and Morgan prepared to temporarily move to Columbus to enroll in Nationwide Children’s outpatient feeding program. There was a two-year waitlist for the spot. It was then that the family learned their insurance wouldn’t preauthorize coverage.

Emily, who works in the insurance industry, managed to identify the insurance broker for her husband’s employer. Emily knew she recommended that the insurance agency deny their claim. She reached out and realized the broker assumed the cost would be exorbitant and the need wasn’t great. “Nobody has any idea what the expense is for each of these children because they all need different types of care at different stages,” she says.

Emily explained that the cost of not covering the program would be much higher if Morgan continued to need an NG tube and years of therapy. She convinced the broker to recommend the approval. “It was very last minute and very stressful. I’m in the industry and know how the game is played, so it was extra frustrating to see this happening to my kid,” she says.

6 tips for insurance appeals

Emily recommends the following tips for navigating insurance denials.

1. Be a fierce advocate for your family and child. When the insurance company denies coverage, insist that you’re not accepting no as an answer.

2. Speak to different people. Talk to your employer’s human resources department to find out how to reach the company broker. Explain to them about the treatment and the cost exposure. They may assume that the costs to treat your child are much more than they are. Present a budget of what your kid needs and what the expenses are.

3. Have a peer buddy who’s navigated this before.

4. Let a family member or friend go to important appointments with you. “In fight or flight mode, you’re not thinking clearly. You may not recognize the whole picture and miss a big piece of information,” says Emily.

5. Take detailed notes. “We hear things differently when we’re in stressful situations,” says Emily. A notebook to refer back to meant she could better advocate for her daughter.

6. Lean on your provider to help you advocate for coverage. Many hospitals have a patient advocate or liaison to help families navigate benefits and the appeal process.

When calling your insurance company, here’s a sample conversation Emily recommends using:

I know you don’t understand the complexities of my child’s condition. She needs speech and language pathology, occupational therapy, feeding therapy with a dietitian, pediatric psychologists and nurse practitioners to deal with this illness. Delaying care can delay my child’s progress and make it more expensive.

I need your help getting me to someone who can help all those codes appropriately process. Can you connect me to someone who has a better understanding of billing for complex conditions?

I’ll stay on the phone until you figure this out.

Navigating insurance for a child with PFD is frustrating, but it’s not impossible. Like so much of parenting, says Emily, “You have to be a fierce mama bear, talk to different people and make someone listen to you.”

Click here to download more information about your right to appeal an insurance denial and access a sample appeal letter template for PFD.

Focus on Food Safety

Published by Anna Busenburg, RD, CSP, LD, CLC on Sep 05, 2023

This blog post is published as part of a paid partnership between Feeding Matters and Reckitt Mead Johnson Nutrition. Learn more about our corporate partnership program and ethical standards for collaboration.

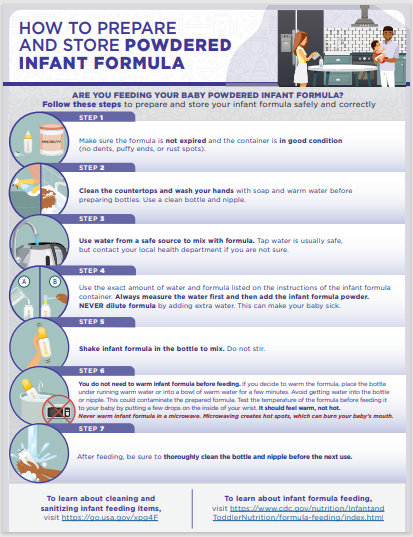

There are many opinions on using human milk or infant formula when it comes to feeding your baby. Most of the focus goes into what is being fed to your child, but less emphasis is placed on the safety of how feedings are prepared. Unless you are directly breastfeeding your child, you need to consider food safety when preparing infant bottles or tube feedings.

This focus on food safety has been front and center over the last couple of years since infant formula recalls have been in the news. These recalls occurred due to microorganism contamination concerns in a manufacturing facility. Food safety matters and is why liquid ready-to-feed or concentrated formulas undergo a heat treatment that sterilizes the product. Powder formulas are not sterilized, which poses an additional risk for contamination when incorrectly handled and prepared. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the regulatory and enforcement authority over the manufacturing and distributing of infant and pediatric formulas. It is important to consider food safety when preparing both infant formula (< 12 months old) and pediatric formulas (> 12 months old) being fed via a bottle or a feeding tube.

For families preparing pediatric feedings at home, it is important to remember these safety tips:

- properly wash your hands

- clean/sanitize feeding equipment and preparation space

- store prepared feedings appropriately

- follow the recipe from your provider

Practicing good hand washing techniques helps to diminish the risk of transmitting germs. Make sure that hands are washed for a full 20 seconds with soap and water. Proper handwashing is the #1 method of preventing the spread of germs for your child.

When bottles or pump parts are being used, cleaning them regularly is essential. It is also recommended to sterilize these components in the microwave or dishwasher. Any child that has complex medical conditions has increased susceptibility to infection. Steps to clean and sterilize equipment are crucial for these children’s overall health.

Any time you mix up formula – those feedings are good to use for 24 hours. Make sure that you label and note of when feedings are mixed and store in the refrigerator until it is time for the feeding. This includes recipes of human milk fortified with formula or formula only recipes. When warming infant feedings, never microwave. Options for warming include a bottle warmer or placing bottle in a warm water bath. When leaving the house with infant feedings, transport in a cooler with ice pack to help ensure the milk/water is kept cold to decrease risk of microbial growth.

When preparing your child’s feedings, follow the recipe on the can or given by your health care provider and check the expiration data prior to preparing. Some children need special feeding recipes to meet their growth goals. Use the scoop in the formula container or measuring utensil provided by your health care provider. Use a safe water source for mixing feedings, this can be tap water or nursery water.

Feeding your child seems like the most basic parenting task, but it can be challenging and complicated for many families. Remembering some of these guidelines of food safety can help ensure that you are doing the best for your child and keeping them safe. Click here to download and print handout from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) our HOW TO PREPARE (cdc.gov)

References:

1. Green Corkins, K., & Shurley, T. (2016). What’s in the Bottle? A Review of Infant Formulas. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 31(6), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533616669362

2. Turck, D. (2012). Safety Aspects in Preparation and Handling of Infant Food. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 60(3), 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338215

3. Green Corkins, K., & Shurley, T. (2016). What’s in the Bottle? A Review of Infant Formulas. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 31(6), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533616669362

4. CDC. (2018, May 7). Infant Formula Preparation and Storage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/infantandtoddlernutrition/formula-feeding/infant-formula-preparation-and-storage.html Accessed August 8th, 2023.

Anna Busenburg, RD, CSP, LD, CLC has been a registered dietitian for the past 11 years and specializes in pediatric nutrition and specifically neonatal nutrition, working in a level IV NICU at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. She has covered inpatient NICU and outpatient NICU follow-up clinic patients.

She has undertaken many projects over the years to help improve patient care and cultivate a culture to support nutrition education. She has been involved in developing a process for utilizing donor breast milk in a 25-bed NICU and she was involved with leading the launch of a breast milk/formula scanning system in a 100-bed NICU. Anna is a certified specialist in pediatrics and has completed the pediatric weight management course. She obtained her Certified Lactation Counselor credential in 2019.

She authored a chapter of the book The Nutrition Communications Guide from AND published in 2020 and published an article in the Pediatric Nutrition Practice Group on RDs Involvement in Infant Feeding Preparation Rooms published in 2019. She currently serves on multiple committees for the Pediatric Nutrition Practice Group and has held various positions within AND on the state and local level. She is also a member of the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. When not busy with work, Anna spends her extra time and energy with her family, which includes her husband, 3 boys, and a Chihuahua.

Pediatric feeding with empathy: 8 ways to think through a compassionate lens

Published by Marsha Dunn Klein, pediatric occupational therapist on Aug 17, 2023

On a vacation to Monterey, Mexico, I sat at a fancy restaurant and friends presented me with a plate of worms. Since I am a curious eater, and it was a delicacy, I cautiously took a bite.

At that moment, I couldn’t help but think of my feeding therapy clients. After decades as a pediatric occupational therapist, I wondered, “If somebody made you eat this, held your hands down while they put it in your mouth, or made you eat three bites of those worms before you could have your regular dinner, would that be fair?”

Understanding how children feel during mealtime is the pediatric feeding with empathy that I try to share in my teachings with parents and feeding therapists. Empathizing with why children struggle to eat or drink is key to setting clients up for a lifetime of better feeding. “We need to look deeper to find a compassionate lens. The foundation for supporting all areas of feeding therapy has to be fully cemented in an understanding of empathy, connection, safety, motivation, enjoyment and brain science.”

In a presentation at the International PFD Conference, I outlined eight mindset shifts to consider for a more empathetic approach to PFD feeding therapy.

Communicate the empathy circle

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. It’s the ability to sense another’s emotion and imagine walking in their shoes. For children and their parents, pediatric feeding with empathy means seeing food as they see it and reflecting to them that they’ve been understood.

Communicating what might be going on for a parent or the child is called the empathy circle. We need to find empathy for the child and what they might be going through. And we need to help parents have empathy for their child and understand what might be going on for them.

Look beyond just calories during mealtime

Nourishing children needs to include more than focusing on calories. Having a child feel like a celebrated part of mealtime is essential to skill mastery. Food is nourishment, but it’s also a means of communication and socialization. It can be about giving and receiving love, celebration and family time. This is why mealtime is an important opportunity to develop strong parent-and-child relationships. We need to ensure we’re also nourishing little souls with pleasant, safe company.

Shifting adult and child roles during meals

The role of adults at mealtime is to decide the menu and provide a safe environment for learning. When children come to the table, it’s to be nourished and have energy for the day. That means some of the foods offered at that mealtime must be foods the child knows and will comfortably eat while they’re learning about other foods that the family and siblings are eating.

Many of us have approached feeding therapy as if it’s our job to “get food into kids.” However, it’s the child’s job to decide what and if they’re going to put food in their mouths, and our job is to offer a variety of foods to allow for opportunity and learning about foods so the child can discover what he LOVES.

Rethink exposure to new foods

In the past, exposure to new foods meant getting a child to put it in their mouth. In some cases, a child gets pushed past their sensory safety zone. Exposure done with pressure can decrease the enjoyment of eating, along with any benefits of that exposure.

Asking a child with PFD to try a mouthful may be way too big of an ask. A little taste, lick, touch or even seeing others enjoy a food can be considered an “exposure.” Instead of thinking of “exposure” where adults often ask (or demand) that children interact with that food in a certain way, can we think of “opportunity” where the child gets to explore the food and decide if or when ready to try it on their own.

Work with the whole family

Both parents and children bring their experiences to the table. A trusted connection with parents from infancy supports a child’s ability to self-regulate. Feeding therapists must be sure to support parents’ success. This means asking assessment questions that reflect what’s going on with a child and parent. It also means including parents in planning and solutions with questions like: Of all the things we did today or talked about today, what would you like to try this week?

Consider why a child says no

A child says no to food for a reason, such as:

- They don’t feel well

- The sensory challenge is too great

- They have a difficult motor response to that food

- They have poor regulation

- They are too worried

Consider food refusal as communication. It invites us to be curious about what’s going on and how we can make that child feel more ready and safe for this mealtime interaction.

Shift from food tolerance to enjoyment

Tolerance is the capacity to endure pain or hardship. But enjoyment means satisfaction, pleasure and gratification. Food constitutes not only the taste but also sensory aspects, socialization, experience and satiation. Many of us have used the word “tolerance” in our feeding goals. But if a child doesn’t like that food, why would we settle for “tolerance” when we could aim for “enjoyment?”

Pay attention to communication cues

Forcing a child to eat when the adult is the more powerful figure in the relationship could mean missing cues of a child’s sense of safety, worries and need to protect themselves. It’s easy to push into their stress and worry zone and then call food refusal a behavior problem. This can unintentionally teach a child to ignore their body and sensory cues.

When we allow children to tune in to the wisdom of their own bodies, we’re supporting safety. Children who experience safety with us as parents and therapists are better able to regulate themselves. Pediatric feeding with empathy means seeing them, hearing them, valuing them and understanding them, to climb into their skin and walk around in it.

Ultimately, eating is a learned behavior. How parents and children interact over mealtimes matters. This is why parents and feeding therapists must do what they can to create positive memories around eating, food and mealtimes.

View Marsha’s International Pediatric Feeding Disorder Conference Session: Shifting our Focus in Pediatric Feeding Towards a Compassionate Lens here

Marsha Dunn Klein has spent over five decades working in feeding therapy as an occupational therapist, author, inventor and co-founder of the Get Permission Institute. This article is based on a presentation from the 2023 Feeding Matters International Conference.

A mother’s journey with PFD shines a light on research

Published by By Hayley Estrem, PhD, RN, Assistant professor at UNCW on Jul 21, 2023

I clearly remember the day a doctor’s news changed my life. After months of chasing my baby around with a bottle to eat an ounce at a time, I learned Alex has a rare chromosome disorder.

The neurologist enthusiastically delivered the devastating news, charmed that he was the first to solve the puzzle of why Alex’s development was delayed. Even as a registered nurse, I found his explanation confusing. My shock meant I couldn’t have processed the information even if it had been simple.

How NOT to support families with pediatric feeding disorder

As a healthcare professional, that day was one of many where I learned how not to support a family of children with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). The news should have come from a genetic counselor, my husband should have been there, and it should have been shared with compassion.

The journey before learning about Alex’s disorder was a struggle as well. Although he was my first, I knew it wasn’t normal for a newborn to eat only an ounce at a time. What he took in, he spat up. His growth was slow, and at 9 months, he was neither sitting up nor crawling.

Our pediatrician told us to give it time, that I was a nervous new mom and that Alex was slow to grow because it was a difficult pregnancy, and he would catch-up. It wasn’t until we saw a different provider at 9 months that we were connected to a neurologist, geneticist and Early Intervention (EI) services. This too, was a lesson in how not to support families of children with PFD.

Armed with a diagnosis and therapy services, we hoped to help Alex eat more and get the calories he needed to grow and develop. Instead, we were told to try harder to feed him and to schedule weekly weigh-ins. A feeding tube was held over our heads like a threat, as if inserting one would signal our failure as parents.

By the time Alex was 18 months and weighing only 16 pounds, I nearly begged for a G-tube. When he finally got one and started gaining weight, I couldn’t help but wonder why we were encouraged to try so hard. Why didn’t he have the nutrition he needed during such a critical developmental time?

Alex’s genetic diagnosis and the PFD that came with it became a springboard for my career. I had a choice to struggle with the question, “Why me?” or do something that would make this odyssey less painful for others.

I chose the latter.

Leading research to support families of children with PFD

After completing a master’s degree in nursing education and then a doctorate in nursing, today I research PFD and how it affects the entire family unit. I’m dedicated to fixing what we went through for others.

At the beginning of Alex’s diagnosis 15 years ago, there wasn’t common terminology among physicians and clinicians. This was a focus for my dissertation because it is a big barrier to building research and supporting families of children with PFD.

It’s why I have a big affinity for Feeding Matters, who did the work to get a PFD ICD-10 diagnosis.

One of the things I’ve done with our Feeding Flock Team is to develop several parent questionnaires about feeding behavior, skill, family management of feeding, and parent and family impact of feeding. For example, on a project with researchers and clinicians at Children’s Hospital of Atlanta, we are developing an assessment of the impact of intense food allergy regiments on caregivers and households.

Our goal is to provide data to clinicians and parents to help determine whether a food allergy intervention eases the psychosocial impact that food allergy has on everyday life for parents and families. For example, new oral immunotherapy treatments for food allergies require children to take a certain amount of allergenic food and have activity restrictions every day at a specific time. Is the cost-benefit worth it? Ultimately, the child still needs to avoid the food, but should have less severe reactions if exposed to small amounts unintentionally. Are there quality of life improvements for the family? We only know if we measure this.

I’ve interviewed parents as I go through the process of developing measurement tools for PFD, and I’ve heard their stories. Witnessing what others go through and being in the position to do something about it is what gives our family’s struggle meaning.

Because of our experience with feeding therapies, I learned to ask more questions. And I learned that research for PFD must be patient-centered. Only with patients who have experienced PFD and their families at the helm can research lead to better journeys and improved outcomes for the whole family.

Thickening Breast Milk with Gelmix: New Guides and Handouts

Published by Gelmix on May 18, 2023

This blog post is part of a corporate partnership with Gelmix.

We’re excited to announce new materials, recipes and guides for thickening breast milk with Gelmix Infant Thickener. Our goal with these materials is to improve caregiver education on thickening breast milk with Gelmix, to provide specific recipes and instructions for use, and to answer our most frequently asked questions about preparation.

First, we have a new demonstration video for thickening breast milk in the healthcare setting. Watch Lindsay M. Stevens, MA, CCC-SLP, Medical Facilities Manager for Parapharma Tech, demonstrate how to thicken breast milk. Lindsay discusses best practices for mixing breast milk in the healthcare setting and reviews recipes to achieve slightly thick, mildly thick, and moderately thick consistencies, including small volume recipes.

Additionally, download and print the new guide to Thickening Breast Milk In the Healthcare Setting which includes product information, mixing instructions and recipes for when thickening breast milk is recommended for swallowing difficulties, or for reducing spit-ups, in the healthcare setting.

Finally, we have two new printable patient handouts available. See Printable Guide to Thickening Breast Milk When Recommended for Reducing Spit-Ups and Printable Guide to Thickening Breast Milk When Recommended for Dysphagia for easy to print preparation guidelines for your patient’s specific thickening needs. These patient handouts are also available in Spanish, Guía Imprimible para Espesar Leche Materna Cuando se recomienda para Disfagia and Guía Imprimible para Espesar Leche Materna Cuando se recomienda para reducir el Reflujo.

Have questions or want to learn more? Visit our website to contact us, to request samples or to schedule a webinar in-service!