Category: Nutrition

What I learned working with a pediatric dietitian

Published by Jalenna Francois on Mar 29, 2023

March is National Nutrition Month! Read along to meet Feeding Matters staff member Jalenna Francois and her experience working with a pediatric dietitian.

Hi! My name is Jalenna Francois. I am the Communications and Awareness Specialist at Feeding Matters. My daughter Sophie was born two years ago (this Friday is her birthday — happy birthday, Soph!). We struggled with feeding pretty immediately after she was born. With the help of a tongue and lip tie revision, lactation consultant, osteopathic manipulation, and the removal of milk from Sophie’s diet, we made huge improvements. I am forever grateful for the early intervention Sophie received, which occurred in part because I’ve worked for Feeding Matters for nearly ten years and know the early signs of a potential pediatric feeding disorder.

Hi! My name is Jalenna Francois. I am the Communications and Awareness Specialist at Feeding Matters. My daughter Sophie was born two years ago (this Friday is her birthday — happy birthday, Soph!). We struggled with feeding pretty immediately after she was born. With the help of a tongue and lip tie revision, lactation consultant, osteopathic manipulation, and the removal of milk from Sophie’s diet, we made huge improvements. I am forever grateful for the early intervention Sophie received, which occurred in part because I’ve worked for Feeding Matters for nearly ten years and know the early signs of a potential pediatric feeding disorder.

As she grew, we discovered she had IgE-Mediated food allergies (what you think of when you hear about food allergies, for Sophie they typically present as hives and wheezing) and FPIES (Food Protein Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome, which presents as vomiting several hours after ingestion of a trigger food). Both of these are comorbid conditions for pediatric feeding disorder.

Our family has been on a long feeding journey over the past two years, and it was changed forever because of our work with a pediatric dietitian. I have learned many lessons from these regular visits with Sophie’s dietitian:

- Nutrition is a lot more than what’s on our plates.

While I did learn about nutrients, how to pair foods, and substitutions to get Sophie what she needed from her limited diet, I also learned that there is a lot more that goes into feeding my family than how many servings of vegetables we get. I learned to acknowledge and set aside the cultural expectations, personal expectations, and the fear and anxiety which wasn’t helping us meet our needs. I learned to meet Sophie where she was with eating. - Meals carry a lot of emotion!

It is so easy to get overwhelmed, anxious, and stressed about feeding my family. Can (or will) Sophie safely eat this? Did she eat enough? Are we eating enough variety? Wow, allergic reactions are scary! As I began to recognize the power this anxiety held over me, I could see it trickling down to my kids as well. At the suggestion of our dietitian, we now check in on emotions before we sit down at the table. There are nights where we can jump right in to eating, but other nights, we need a family story time to connect, take off the pressure, and enjoy just being together before we eat. Creating this feeling of connection and safety before we get to the table has helped to reduce the immediate ‘YUCK’ my 4-year old likes to react with when she sees the foods being offered. - Lead by example.

For me, this has looked like taking intentional time to feed myself food that is nourishing and enjoyable. I don’t let my kids skip meals, and I am trying to treat myself the same way. I have learned to incorporate all foods I enjoy without guilt, in a balanced way. Caring for myself will only benefit my children as well. - Give yourself grace. Feeding is a journey, and progress is more important than perfection.

Not every meal is going to go perfectly, not every food is going to be accepted, even after 100 exposures. Having patience with myself and my children as we learn together is building the trust we all need to make progress. - The power of having someone in your corner.

Having someone to talk over meal plans and strategies for food introductions and substitutions was huge. But what I remember from the beginning of our journey with our dietitian was having someone to help me see hope when our feeding experiences felt overwhelming, never-ending, or unfair. Having someone who gets it and is able to help you see the possibilities ahead is a game changer. (Pro tip: Looking for someone to be in your corner? Check out the Feeding Matters Power of Two program.)

By now, I’m sure you can tell that my dietitian is awesome! Not only is she a great dietitian, she shares her extensive knowledge on her Instagram and blog so that everyone can learn like I have. She also recently became a Feeding Matters board member, which is just one way she is as a champion for children with PFD.

By now, I’m sure you can tell that my dietitian is awesome! Not only is she a great dietitian, she shares her extensive knowledge on her Instagram and blog so that everyone can learn like I have. She also recently became a Feeding Matters board member, which is just one way she is as a champion for children with PFD.

As we celebrate Sophie’s second birthday this week, I am so proud of the progress our family has made together. I never imagined we would make it to where we are today, and I look forward to seeing where the rest of our journey takes us, with our dietitian by our side.

Pass on the peas; pass the pizza, please

Published by By Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES on Mar 24, 2023

Is your child getting enough nutritional variety? How to know and what to do about it

By Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES

Mass General for Children Pediatric Nutrition Center of Excellence, Center for Feeding and Nutrition

Nutritional variety for children ages 0-5 is extremely important to the growth and development that happens in those early years. That said, it’s normal for young children – especially toddlers – to go through phases of picky eating as they explore their world and assert their independence. In honor of National Nutrition Month this March, read the blog below from expert pediatric dietitian Simona Lourakas of Mass General Hospital for Children to know what to expect when feeding young children and how to ensure they get the nutritional variety they need.

When your baby starts eating solid foods, it’s not uncommon to expect that transition to go well. No matter that the foods are only as exciting as room temperature, smashed peas. Other tots the same age are happily gumming blended foods.

But, as hard as you try, your child refuses to eat many of the foods you offer. Is this a sign of age-appropriate picky eating? Or is it an indicator of a more significant issue?

What is nutrition variety?

Nutritional variety for adults and children means eating foods from all food groups: grains, proteins, dairy, fruit and veggies. There are other calcium fortified foods for those who can’t eat dairy. And many fruits and veggies have a lot of nutrition overlap.

Exposing kids to solids builds up their feeding and oral motor skills. It helps prevent food allergies later on and increases diversity in the gut. For breastfed infants, iron-rich proteins can be an important food group such as iron fortified cereals, beans, leafy vegetables and lean meats.

At around nine months old, a limited variety or quantity of solids will start to impact growth, nutrition and oral-motor skills.

Why nutrition is so crucial for young children ages 0-5

Nutritional variety is critical, affecting every area of children’s growth and development. A study conducted by Feeding America shows that malnourished children:

- Cannot learn as much, as fast, or as well as peers

- Have more social and behavioral problems because they feel bad and have less energy

- Require frequent doctors’ visits

- Are at risk for cognitive development during this critical period of rapid brain growth

The kinds of nutrition, care, stimulation and love children receive during these critical first years of life determine the brain’s architecture and central nervous system. Identifying and treating feeding and nutrition problems are crucial to supporting children’s cognitive, physical, emotional and social development, as well as the caregiver-child relationship.

How to know if your kid is getting enough nutritional variety

Like anything in parenting, there’s a lot of pressure to compare your child’s eating to peers, especially once children enter daycare or preschool. This only adds to the stress parents can already feel around feeding their children and ensuring they get the nutritional variety they need.

Considering the size of your hand to your child’s hand is a good reminder of how small a child’s portions need to be. A portion of protein is only about the size of the child’s palm. A grain serving is the size of a closed fist.

Most children will not eat all five food groups in a meal and maybe not even in a day. Instead, consider what your child eats over the week. They’re likely getting enough nutritional variety if they eat foods from all food groups over that period.

What to do if you’re concerned

Developing a healthy eater is challenging for many parents. Even for children without any feeding issues, this can take time, patience and persistence. Children with food allergies, autism, sensory concerns, premature birth or medical complications will need a more specialized approach to eating.

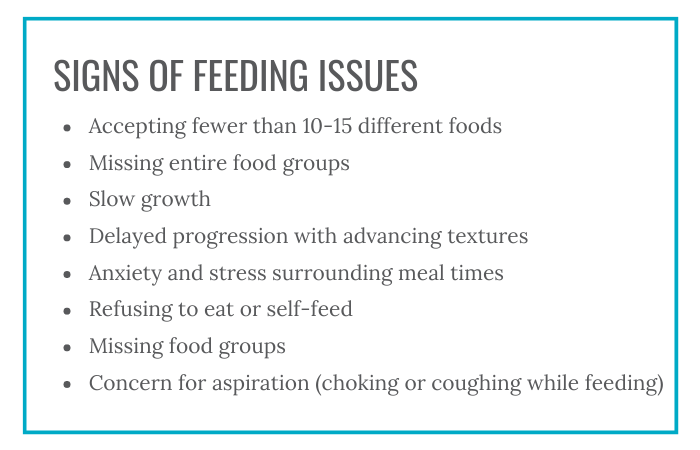

Following are some signs of feeding issues:

- Accepting fewer than 10-15 different foods

- Missing entire food groups

- Slow growth

- Delayed progression with advancing textures

- Anxiety and stress surrounding meal times

- Refusing to eat or self-feed

- Missing food groups

- Concern for aspiration (choking or coughing while feeding)

Speak to your pediatrician if you are concerned about your child’s eating or nutritional variety.

Tips for parents to add nutritional variety to kids’ diets

1. Know that picky eating is normal for toddlers.

It’s normal for toddlers to have food preferences, such as more fruits vs. vegetables, grains and dairy.

2. Consider adding fortified foods or nutritional supplements.

For children who can’t have dairy, some fortified pea or soy milks are a suitable replacement. For children who are missing other food groups, fortified foods like cereals or supplements, like an age-appropriate multivitamin or formula, can make up for some of that missing nutritional variety.

3. Introducing new foods takes time.

It can take offering a food 10 or more times before a child will accept it. Add new foods with nutritional variety together with familiar foods. This will reduce the pressure or forcing your child might feel.

3. Involve your child. Children of all ages can help prepare and choose foods in safe, age-appropriate ways.

4. Allow children to play with new foods.

Food play is a great way to introduce new tastes and textures without making children feel pressured to try it. Some of the new food will often end up in young children’s mouths this way.

5. Avoiding grazing.

After one year, aim for three meals a day, with 1-2 snacks. Offer appropriate amounts of milk. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests 16-24 ounces per day of whole cow’s milk for 1-2 years and 16 ounces per day of low fat milk children 2+ years. Avoid juice. Grazing all day affects appetite at meal times.

Parents are doing their best

When it comes to feeding your child, know that how much your child eats doesn’t define how well you’re parenting. A parent’s job is to provide food and age-appropriate nutritional variety. It’s the child’s job to eat it.

Parents who offer food in the same way to siblings may find that one has feeding difficulties while the others don’t. As hard as it is to keep from comparing children to peers, including siblings, know that feeding issues are complex.

If you’re concerned about your child’s feeding, know you are not alone. Early detection and treatment of pediatric feeding disorder is critical to affected children’s long-term health and well-being. Check out our six-question screening tool on our website and reach out if you need more support.

Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES is a registered dietitian in Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition at Mass General for Children, a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. She also works with post-acute care rehab Franciscan Children’s.