PFD, ARFID or both?

Published by Will Sharp, PhD on Jun 12, 2023

Developing common terminology for children with PFD and ARFID is key to improving diagnosis and treatment

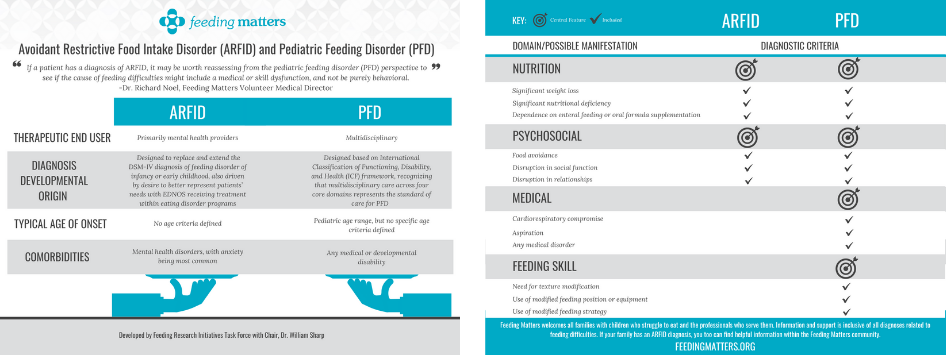

By William Sharp, PhD is a behavioral psychologist and director at theChildren’s Multidisciplinary Feeding Program at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Naming pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) as a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code in 2020 provided much-needed clarity for clinicians and parents alike. For the first time, parents whose children faced feeding problems caused by medical and/or developmental conditions, such as premature birth or autism, could identify and discuss their struggle. Primary care physicians, often called upon to identify PFD, could use the diagnosis to facilitate referrals. Clinicians had an insurance billing code to use when providing care. When everyone shares a common language, finding solutions and improving outcomes becomes easier. But confusion remains. Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is also a relatively new psychiatric diagnosis, introduced in 2013 in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5 code. ARFID describes food restriction and avoidance that may occur in infancy and early childhood. It overlaps with PFD, which is confusing for families and clinicians. The question is, when is ARFID actually PFD? And do you treat ARFID differently if a child has a history of PFD? Defining the differences and similarities between PFD and ARFID is the next step in clarifying both diagnoses and improving support for children who experience them.Defining ARFID and PFD

Let’s break down the diagnoses, their similarities and differences. ARFID is a mental health diagnosis describing children with feeding problems and related nutritional risk or deficiency without coincident body image problems, as seen in anorexia. Children with ARFID have one or more of four symptoms:- Weight loss

- Significant nutritional deficiency

- Dependence on internal feeding or nutritional supplements

- Significant interference with your day-to-day functioning

- Medical

- Nutrition

- Feeding skill

- Psychosocial

Defining the gray area between ARFID vs. PFD matters

Intensive, multidisciplinary pediatric feeding centers like at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta are rare, with only approximately 16 comprehensive clinics in the U.S. Altogether, they provide intensive intervention for about 700 kids yearly. Conservative evaluations estimate that PFD affects more than 1 in 37 children under five in the U.S. annually. Instead of accessing support at feeding centers, children with feeding issues may land on the doorsteps of eating disorder clinics. Sometimes these children have PFD that was never treated at a young age. Here’s an example of a typical child in our feeding clinic: A child was born prematurely and required intubated to aid with breathing. She also had poor motor skills and required a feeding tube to meet all her nutritional needs. She remained on the feeding tube throughout infancy due to concerns with aspiration and swallow safety. At this point, she was diagnosed with PFD. Once medically cleared for oral feeding, a speech therapist worked with the child to introduce pureed food. However, she refused many foods, limiting the volume and variety of food she would eat. These behaviors worsened overtime. After two years of weekly feeding therapy, she was referred to a multidisciplinary feeding program, where she was diagnosed by a psychologist with ARFID. Like the patient above, ARFID may begin not as psychological diagnosis. Instead, it’s a response to a medical complexity. A physical challenge became a behavioral challenge. Supporting this child and millions like her means addressing both. This also highlights the potential connection between PFD and ARFID, a connection that caregivers and clinicians may find confusing. Coming together to improve care for children with PFD and ARFID

Coming together to improve care for children with PFD and ARFID

Ensuring the needs of children with PFD and ARFID are being met requires coming together as a community of multidisciplinary clinicians treating them.

As part of the Feeding Matters research task force, we conducted a national survey of 650 providers assessing and treating PFD. It’s the largest survey of its kind, and responses are key to identifying existing support and current needs. We expect to publish survey results this summer 2023.

Armed with that information, we can start to develop common terminology for PFD and ARFID. Together with Feeding Matters, our Feeding Clinic at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and Emory University will host a summit in August to begin this conversation.

One possible clarifying solution is to have subcategories of both diagnoses. Subtypes would root each diagnosis in a patient’s history. This would mean children fall into four categories:

- PFD

- ARFID

- PFD with an ARFID subtype

- ARFID with a PFD subtype

William Sharp, PhD is a behavioral psychiatrist and director of Children’s Multidisciplinary Feeding Program at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. He’s a medical advisor to Feeding Matters and is helping shape the PFD and ARFID conversation.