Author: Jalenna Francois

FROM THE PFD ALLIANCE: A FOCUS ON EDUCATION

Published by Amy Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP on Mar 22, 2023

As we approach our 10th Annual International PFD Conference, I look forward to learning from expert colleagues about new ideas and strategies that we can use in the care of children with PFD. It comforts me knowing that Feeding Matters has worked diligently to offer content that has been both reviewed for bias and is rooted in evidence. This makes me reflect on the current educational landscape and how it has changed over time.

Thinking back to when I first entered the field (and yes, I’m aging myself), sources for educational content were textbooks and hard copies of journal articles, either arriving in my mailbox or checked out by me at the library. Unfortunately, these old-school sources were nearly outdated by the time they entered my hands. In-person conferences were the only method for me to learn what things were at the cutting edge from my peers and scientists in the field.

Learning today has never been easier! Today’s technology affords endless formats and venues from which we receive information. We have access to first-hand information directly from researchers, clinical experts, and parents. We see examples of different disorders and impairments and clinically validated intervention strategies while standing in line for coffee, or even while on a walk.

Unfortunately, access to everything all the time can be overwhelming, and it may be difficult for a learner to navigate material without a good understanding of its strengths and potential weaknesses. It may seem that everyone is an expert and it’s hard to discern that the information being shared may not be objective, evidence-based, and/or appropriately interpreted. It may be difficult to know which sources to prioritize for one’s learning.

What are my best options? Who am I listening to and what is the underlying evidence? For social media, if one source has more followers than another, is it more likely to be correct or validated? Who is vetting the information? Here are a few pitfalls to keep in mind:

- Saying something with confidence and fancy graphics does not make it sound evidence.

- A greater number of followers does not guarantee information is superior to that from a source with fewer followers.

- Be mindful of individuals who discount or contradict what you have learned to be reliable and clinically validated information.

- Conversely, be mindful of individuals who purport that information is accurate because it’s how it has always been done.

- Is the information based on published studies or other peer-reviewed content?

- Is the source only promoting a product?

- Is the source acting in a professional manner that is ethical and considerate of other opinions?

As we continue to navigate our educational options, consider some of the following suggestions:

- Use multiple sources for learning. Maintain a broad diet of information that includes social media, webinars, and in-person meetings. A broad educational repertoire is always best.

- Dig a little deeper into a new source of information. Learn about your favorite vloggers and what their experience may be. What is their profession and their training? What population of children do they see? Know who you are listening to and trusting to contribute to your clinical journey.

- Think critically about what you’re learning. Does it make sense? Does it continue to enhance your knowledge and practice? Does it contradict well-known evidence?

- Rely on your professional organizations to review the current state of information and evidence and provide experienced perspective on how new ideas may fit into established paradigms.

- Advocate that we need pediatric feeding and swallowing taught at the university level to give everyone a foundation.

We, as a community of PFD providers and families, must lift each other and support each other in our learning to advance the field and the lives of children and families with PFD.

Amy L. Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP

Amy L. Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP

PFD Alliance Education Chair

Why clinicians should attend the PFD conference

Published by Brianna Miluk, MS, CCC-SLP, CLC on Mar 08, 2023

The Pediatric Feeding Disorder conference emphasizes kindness, community and communication

The first time I joined the International Pediatric Feeding Disorder (PFD) Conference, I sat alone in my sunny South Carolina office, anticipating a typical academic research virtual presentation that would count for some CEUs.

Instead, what I found was relatable and practical content that I wanted to share with every clinician I knew.

I’ll never forget a particular workshop by Dr. Kay Toomey on Picky Eaters vs. PFD vs. ARFID: Differential Diagnosis Decision Tree. At one point, I got so excited about the presentation that I leaped out of my chair and clapped enthusiastically. Now, anyone who knows me sees that I have a lot of energy, so this wasn’t totally out of character. Still, I’ll admit I looked a little strange in my office, shouting with glee. When my husband came running, I couldn’t resist exclaiming, “THIS IS SO GOOD!”

It’s no exaggeration to say that the first time I attended the Feeding Matters International Pediatric Feeding Disorder virtual conference in 2018, I was hooked.

The conference isn’t just an opportunity to check off your requirements box for ASHA, AOTA or ACCME. It’s a virtual gathering of clinicians and families all motivated by a singular goal: helping more children and families access the care they need for pediatric feeding disorder.

As part of the conference planning committee for 2023, I can attest that our goal for every presentation is to deliver practical takeaways for families and clinicians. This is part of what makes the PFD conference so powerful.

It’s tricky to organize a virtual conference. Besides any potential technical glitches, creating a sense of community and conversation is challenging. But the PFD conference is unlike any other I’ve attended. There’s a sense of kindness, community, and communication that all attendees feel throughout the program.

What clinicians will benefit from the PFD conference

The PFD conference is ideal for any clinician serving children with feeding issues from birth through adulthood. This includes:

- Occupational therapists

- Speech and language pathologists

- Dieticians

- Physicians

Because the program is so family-driven, I even encourage caregivers to attend. Everyone benefits when they learn about different methods and what the research shows.

4 reasons to attend the PFD conference

There are many reasons to take time from your busy clinical schedule to attend the conference. The following are just a few.

Learn practical, innovative interventions and strategies – and how to apply them with families

Like any continuing education, the pediatric feeding disorder conference highlights the latest research and interventions. This conference is different because the presenters go one step further to show how to apply that information to our day-to-day work. Every course I attended focused on how an intervention is only as good as it is for an individual family. As a speech therapist, I see how this mindset matters. I can have all the research in the world at my fingertips, but it’s not practical if none of it works for the family in front of me. That clear focus across all the workshops means that at the PFD conference, I can walk away with strategies to apply immediately.

Build connections across fields

Making friends and forging new professional relationships is not usually a goal for a virtual conference, but that’s what happened at the PFD conference. The chat is active, and the people are friendly. I’ve made real-life friendships with clinicians in my area. I would never have met them outside of that opportunity.

When providers of various backgrounds work together, patients benefit.

Become a stronger advocate for clients

The PFD conference has helped me grow both in my practice and as a patient advocate. I’ve gained knowledge and leadership skills that help me articulate what my clients need, especially when working with other clinicians who aren’t as familiar with PFD and the diagnostic code.

Each year, I leave with a strong call to action to continue advocating for children with PFD and their families. The conference empowers clinicians to hold each other accountable for higher standards of care.

Raise awareness of how trauma-informed care relates to PFD

I’m most excited about this year’s conference’s keynote address, Healing Feeding Trauma: It takes a village, from Dr. Anka Roberto DNP, MSN-MPH, APRN, PMHNP-BC. Bridging the gap in education on how trauma-informed care is essential to treatment for PFD is so important. Spotlighting this topic as the keynote underscores how important it is to heal feeding trauma for the child and the entire family unit.

Every year I’ve attended the PFD conference is better than the last. I don’t doubt that this year’s 10th annual conference will be the best one yet. See you at the conference!

The 10th annual international PFD virtual conference is April 13-15. Register, see our schedule and speaker roster and more here.

Brianna (Bri) Miluk is a speech-language pathologist and certified lactation counselor in Greenville, South Carolina. She has a clinical focus on pediatric feeding and swallowing in infant and medically complex patient populations. Bri is an advocate for information literacy, evidence-based practice, and trauma-informed care, including neurodiversity-affirming practices. She is also an Instructor for Pennsylvania Western University. She is a PhD student with a research focus on disseminating or research and misinformation in speech language pathology on social media. She hosts the podcast, The Feeding Pod, and teaches the Pediatric Feeding Mentorship Group course. Follow her on Instagram @pediatricfeedingslp.

Parents’ Guide to Helping Your Baby with Slow Growth: Expert Tips and Advice

Published by Mary Anthony, RN on Mar 03, 2023

Pediatric developmental nurse answers questions on slow growth, lack of growth, weight loss

Expectant parents have all sorts of worries leading up to birth, but feeding your baby and slow growth usually aren’t among them. You assume your newborn will suck from the breast or a bottle. When this doesn’t happen easily, bringing home your baby becomes more complicated.

Babies with slow growth, lack of growth or weight loss typically spent some time in the NICU and may even have a tube to supplement feeding.

In many cases I see, parents are sent home without a feeding plan when their babies are discharged.

What causes slow growth, lack of growth or weight loss in infants

There are many reasons infants experience slow growth, lack of growth or weight loss, which can all sometimes be called failure to thrive. Common ones include:- Premature birth

- Trouble latching

- Reflux

- Medical conditions

I’ve seen countless overwhelmed parents caring for newborns who require extra support for feeding. This is challenging in the best of circumstances when parents have a lot of help from family and friends.

It’s nearly impossible for those with fewer resources.

Families need more support

First time parents are inundated with an overwhelming amount of new information. The learning curve for managing a newborn is significantly compounded when the baby has slow growth, a lack of growth or weight loss. This is often called “failure to thrive.”

Parents of these babies often lack all the tools and information they need to help their babies grow and thrive.

It’s my job in Maricopa County, Arizona to fill that gap.

In one telehealth visit, I spoke to a mom whose baby was born at 24 weeks and had an NG-tube. Through our conversation, I learned she had a formula prescription, but she didn’t have a feeding plan.

The mom didn’t know when to increase the amount of formula, when to offer oral feedings or even when to visit a gastroenterologist (GI). I helped her develop a plan and get an appointment. Her experience wasn’t unusual.

When a baby leaves the hospital with a feeding tube or after treatment for weight loss or slow growth, hospital doctors assume that pediatricians will ensure the baby’s feeding needs are met. Pediatricians assume the GI manages the feeding plan. And the GI often doesn’t see the baby for months.

More support for these families can make the transition to home easier.

In Arizona, any baby who’s in the NICU for five days or more is eligible for support from a pediatric developmental nurse for up to three years. This includes at least four visits a year in the first year.

I’ve seen firsthand how support is crucial for overwhelmed parents, especially within 14 days of discharge.

Customized care to help babies with slow growth thrive

The causes of slow growth and weight loss are many. This makes one-on-one consultations essential to diagnosing the problem and providing customized support.

In one extreme case, a baby was admitted to the hospital for feeding issues and weight loss. After discharge, I made a home visit and asked the mom to show me how she feeds the baby. She only had one bottle and a nipple caked with dried powder. This baby was sent to the hospital for feeding issues, but nobody assessed the mom to see what she was actually doing at home to feed the baby.

In another case, I met with a mom whose baby was discharged without adequate supplies for her baby’s feeding tube. She adjusted the baby’s formula and was adding her own mixes. She needed more adhesive to keep the NG-tube inserted, so she used adult Tegaderm. Still, the tube wasn’t staying in place. While they had already visited the pediatrician, the mom hadn’t communicated her challenges because she didn’t know any differently.

It’s these kinds of early struggles that can make developing pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) more likely, even for those children who outgrow their initial challenges. Getting these families access to early support can make all the difference.

How parents can improve feedings at home in cases of slow growth, weight loss or feeding tubes

Ask for a feeding plan

Key to helping parents deal with feeding challenges is providing better instructions when children are discharged from the hospital. NICU nurses are great about showing parents how to insert the NG tube, check placement and when to call for help.

Be sure to also ask when to increase the calories, when to visit a GI and when your child no longer needs the tube.

Get emotional support

With all the focus on feeding a baby with slow growth, lack of growth or weight loss, it’s hard to focus on self care. But it’s essential.

Moms need rest and breaks, especially those who are postpartum and are double feeding – pumping and giving bottles. Rally your support among family and friends. Don’t expect to be able to handle everything alone.

Set up a treatment space in your home

If your baby has a feeding tube, it’s important to designate a treatment space. Make sure this isn’t a crib, couch or play area. This helps your baby know what to expect, rather than fear having the tube inserted at any point in the day.

Hold your baby during feedings

Whether you’re bottle feeding or tube feeding, it’s important that you hold your baby during feedings. This helps with bonding and makes your child feel more comfortable eating.

Get in touch with Feeding Matters

If you’re struggling with feeding challenges, you don’t have to walk this road alone. At Feeding Matters, we have many resources for parents to answer questions and provide social and emotional support. One of our most helpful support programs is peer to peer mentoring, Power of Two.

Ensuring parents get support for slow growth, lack of growth and weight loss is crucial to mitigating the risks of developing pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). Not all parents will have access to a pediatric developmental nurse, home health or coordinated support between their pediatrician and a GI. It’s essential that parents get the information they need from the start, before being released from the NICU.

Babies and their parents depend on it.

Mary Anthony has been a pediatric nurse for nearly 40 years and is head of the High Risk Perinatal Program for Maricopa County in Arizona.

Power in Pause, Power in Reflection

Published by Jaclyn Pederson, MHI on Feb 22, 2023

Dear Friends of Feeding Matters,

I am so pleased to be back after a wonderful (and messy and loud!) maternity leave. I return ready to fiercely advocate for children with PFD, their families, and the professionals who treat them.

A lesson that has helped me recently in coming back after maternity leave is finding power in the pause. Much of what I do here at Feeding Matters involves thinking, setting strategy, and empowering the team. We have goals that will take 15 years to accomplish and some that will take three months. It can be easy to get pulled into one of the many areas of the PFD system of care that need attention and admittedly, it is sometimes hard not to react. But I’m learning there is power in pause and power in reflection. This space allows me and the Feeding Matters team to stay focused on strategy and the areas that will make the largest impact.

With this focus on our strategy, I have a few general aims that I hope to achieve for Feeding Matters and our internal team:

- Trauma Informed, Healing Organization: While I do believe most of our programs are trauma-informed, we are never done learning and need to be constantly evolving and growing. I want to ensure that we are trauma informed in all of our programming and continue to grow as a healing organization aware of trauma and its impact to an individual and a system.

- More Content: We are working to bring you more educational and awareness content that supports the needs of parents, professionals, and caregivers. This includes webinars, blogs, articles, and more.

- A Greater Movement for PFD: As we continue to build awareness for pediatric feeding disorder, we are creating a movement to ensure children are identified early and have access to the support and treatment that they need. This year, that movement will get even stronger. To start, we will have the biggest PFD Awareness Month (May) yet!

- A united community: Often, Feeding Matters has served as a neutral place for all perspectives to exist and ideas to be shared and discussed. We aim to continue this effort and take great pride in this responsibility. But as the world of feeding continues to get more complex, this task becomes even more difficult. That is why we remain dedicated to listening to our community, working toward consensus, advancing research, and innovation in an ever-evolving field.

For myself, and what I hope to bring to my team, is to continue working on living and breathing our values daily. Our team values are collaboration, innovation, and inclusion. We work to grow each day as leaders serving our community so that we can achieve our vision of creating a world where children with PFD will thrive. To do this, we will ensure we always make time for and find power in the pause.

Happy to be back,

Jaclyn

Jaclyn Pederson, MHI

Feeding Matters CEO

best practices within intensive care settings

Published by Erin Ross, PhD, CCC-SLP on Feb 14, 2023

Feeding begins at birth, and for many infants who are born preterm or with medical complications, feeding experiences happen within intensive care units. An international consensus committee has published standards and competencies for best practices within intensive care settings. Currently there are six general areas that are covered by these recommended practices. One is for feeding, eating and nutrition delivery. This is a great resource for people working within intensive care settings with infants – whether in neonatal or cardiac units or other specialty units. There are eleven standards within this area, with multiple competencies within each. Rationale for each standard, along with the body of evidence used to create the standard, are freely accessible. There are also checklists available to measure your current practice.

A common question is “but how do I do this?” Feeding is multi-dimensional and making any changes to current practices can be very overwhelming. Recently a “put into practice” conference produced a White Paper that is also available. I am including this resource for you here.

If you ever wanted to compare where you are (personally or within your unit) with what is possible, this is the place for you. Check it out – and keep coming back. It is currently in the process of being updated with new research and the standards are being evaluated. In fact – you have the opportunity to provide feedback for this process as well – all on the website here.

Does your child need a feeding tube? Here’s what you need to know

Published by Dana Williams, MD on Feb 09, 2023

A pediatric gastroenterologist debunks 4 myths about G-tubes and normalizes a feeding tube for those kids who need it.

Dana Williams, MD, Medical Director, Feeding Disorders Multidisciplinary program; Medical Director, Aerodigestive Digestive Program at Phoenix Children’s Hospital

Dana Williams, MD, Medical Director, Feeding Disorders Multidisciplinary program; Medical Director, Aerodigestive Digestive Program at Phoenix Children’s Hospital

When I see patients who are likely candidates for a G-tube, I can already imagine their lives at home. Days revolve around feedings. Every hour, on the hour, the parents attempt to get an ounce of formula or breastmilk into their little one’s belly. The parents are exhausted, and so are their children. Everyone feels like a failure.

In spite of the struggle, no one wants to bring up a G-tube. So, I do.

As director of a team of physicians, therapists and dietitians at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, I see hundreds of children each year with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). For many of them whose medical complexities make oral eating a struggle, a gastrostomy (G) tube is a key medical intervention. G-tubes help these children develop and thrive, while preventing malnutrition and dehydration.

A G-tube is surgically inserted through the abdominal wall and into the stomach. It’s held in place by an internal device called a balloon. The tube can be used to deliver liquids, purees and medication.

This sounds scarier than it is.

Like any surgical medical intervention, deciding to directly feed a child through a gastrointestinal tube inserted into their stomach is a big decision. For those children who are a good candidate for a G-tube, the benefits of a feeding tube and the risks of not getting one far outweigh any risks.

There are many benefits of getting a G-tube. Some of those include:

- Improved nutrition and hydration: A G-tube provides direct access to the stomach for nutrition, fluids and medication, ensuring children get the nutrition they need.

- Reduced risk of aspiration: A G-tube can reduce the risk of food and liquid entering the lungs, a common problem for children with pediatric feeding disorders.

- Increased independence: Children with G-tubes can engage in activities they enjoy without the stress of constantly worrying about eating or drinking.

- Better sleep: A G-tube can provide continuous nutrition and hydration overnight, leading to better sleep and improved overall health.

- Eased caregiver burden: Parents get relief from constantly trying to provide adequate nutrition and hydration.

- Improved weight gain and development: Children with a G-tube often see improved weight gain, leading to better overall health.

- Comfort: Removing the alternative temporary nasal tube can make it more comfortable for a child to eat. Depending on each child’s medical journey, they may be more likely to eat when they don’t have hardware in their noses.

Still, many parents who consider a G-tube for their children can feel like a failure. The truth is the opposite. Feeding isn’t something parents or doctors or anybody can control. If a child doesn’t want to eat, or they can’t eat, then there is nothing anyone can do to make them. Of course, this can change over time with multiple levels of support. But the parents of these children haven’t failed.

Debunking 4 major myths about G-tubes

Most of the time that parents express hesitation about the G-tube, it’s because of a fear of one or more of four common myths. Talking about the reality of what a G-tube will mean for a child and the family helps parents make an informed decision.

Myth #1: A G-tube is permanent

A G-tube is a temporary solution to supplement or replace oral eating and drinking. I have countless patients living healthy lives after the removal of their G-tubes who will attest to that fact.

How long each patient needs a G-tube and whether they’re receiving all or some nutrition through the tube depends on each child’s needs. When a family is deciding about G-tube surgery, we discuss the anticipated use. In many cases, a G-tube can supplement – rather than replace – oral eating.

We also discuss the process for removing a G-tube for those kids who can eat fully orally one day.

Myth #2: Infection is common with a G-tube

Infections do occur for some people with a G-tube, but they’re not common. Some children are more sensitive, and there is no way to predict that. For most people, the channel for the G-tube heals nicely. Similarly to an ear piercing, it becomes epithelialized so that the tube can comfortably pass through the area. We monitor the insertion hole and mitigate the risk of infection by teaching parents and older children how to clean the area.

Myth #3: Kids can’t eat regular food with a G-tube

The majority of kids with G-tubes in our practice also eat orally. This varies for each child, depending on their medical issues. Most children I see even take pleasure in oral food. The G-tube is an important tool that gives children time to develop the ability to eat on their own terms.

Myth #4: A G-tube means kids won’t be motivated to eat orally

While there is some truth to this myth, it’s not entirely accurate. For many kids with PFD, it doesn’t take much for them to feel full. This is why we individualize treatment so that each child receives the amount they need. Children can still learn hunger cues and get exposed to meal time routines.

What is a sign of success for a child with a feeding tube?

Just as the treatment plan for every child with a feeding tube is different, success also varies. To me, the main signifier of success is when the patient and family are in close conversation with their doctor. Every journey is different, but having a team of the right medical provider matters. It’s not up to parents to walk this journey alone.

Beyond that, any step forward for a child is success. Some examples are as follows:

- A child who aspirates due to a medical condition safely learns to taste some food and enjoy family meals.

- A child slowly learns to eat orally through feeding therapy post heart surgery.

- A child who outgrows some allergies and tries more foods.

- A young adult who goes off to college even though he still only eats seven foods.

Parents of children with pediatric feeding disorder no doubt feel responsible for ensuring their children get the nutrition they need to grow and develop. For those children who are good candidates for a feeding tube, a G-tube is an important tool to help them along their feeding journey.

Hadyn Van der Molen has had a G-tube since he was nine months old. His mom, Heidi, program manager for Feeding Matters, recalls feeding Hadyn around the clock with a 2-oz. bottle. The only time he’d ingest it was when he was sleeping.

Mighty Milk or Diet Diversity?

Published by Raquel Durban, MS, RD, LDN on Feb 01, 2023

This blog post is published as part of a paid partnership between Feeding Matters and Reckitt Mead Johnson. Learn more about our corporate partnership program and ethical standards for collaboration.

Food shopping has evolved over the years. Long gone are the days of only cow’s milk or soy milk. Now it seems there is milk made from every type of plant! You will likely find yourself questioning, “which is best for me?” or “is there a better option to use as a replacement in cooking or baking?”.

The range of alternative milk beverages includes almond, cashew, soy, coconut, pea, oat, walnut, flax, hemp, macadamia, and rice – as well as what seems like a new option each week!

The nutrients are just as varied as the plants from which they are derived. The question is, “Which milk is best for ME?” because your nutrition needs, and taste preferences will differ from another person’s.

The nutrients in cow’s milk are protein, calcium, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin B12, riboflavin, niacin, phosphorous, pantothenic acid, zinc, selenium, iodine, and potassium.

Avoiding cow’s milk does not mean you have to miss out on its great nutrition! Other sources of these nutrients include:

- Protein: meats, beans, some plant-based milk.

- Vitamin A: beef liver, sweet potato, carrots, cantaloupe, red bell peppers, fortified cereals, mango, spinach.

- Vitamin b12: beef liver, clams, tuna, fortified nutritional yeast, salmon, beef.

- Riboflavin: beef liver, fortified breakfast cereals, beef, clams, almonds.

- Niacin: beef liver, chicken or turkey breast, prepared marinara sauce, salmon, tuna, pork, beef, rice, fortified breakfast cereals, russet potato.

- Phosphorus: salmon, scallops, chicken breast, lentils, beef, cashews, russet potato, kidney beans, brown rice, peas, oats, egg.

- Pantothenic acid: beef liver, fortified breakfast cereal, shitake mushrooms, sunflower seeds, chicken breast, tuna, avocado.

- Zinc: oysters, beef, crab, lobster, pork, baked beans, fortified breakfast cereals, dark meat chicken, pumpkin seeds, cashews, chickpeas.

- Selenium: Brazil nuts, tuna, halibut, sardine, pork, shrimp, enriched pasta, beef, turkey, chicken, egg, and brown rice.

- Iodine: most enriched grains and iodized salt.

- Potassium: apricot, lentils, squash, prunes, raisins, potato, kidney beans, orange juice, soy, banana, chicken breast, salmon.

Here are some tips when shopping for your new favorite:

- Choose unsweetened varieties with little to no added sugar. Those labeled “original” often contain large amounts of added sugar that add up quickly.

- If using plant-based milk to replace cow’s milk, choose one fortified with calcium and vitamin D.

- Children ages 1-2 should receive full-fat versions with a nutrient content similar to whole cow’s milk. Adults, however, can consider low-fat and fat-free versions.

Reference: https://ods.od.nih.gov/

Raquel Durban, MS, RD, LDN is a registered dietitian specializing in the dietary management of families with food allergies. She received her master of science degree in nutrition from the University of Maryland and completed a nutrition internship at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. As a recognized authority on the dietary and nutritional management of food allergies, she is a frequently invited speaker at allergy and immunology conferences and has the pleasurer of precepting dietetic interns. Ms. Durban has contributed her expertise to peer-reviewed publications and continuing education programs.

Ms. Durban is a steering committee member and cochairs the internship program of the International Network of Dietitians and Nutritionists in Allergy and serves on the Medical Advisory Board of the International Association or Food Protein Enterocolitis. She plays and active role in the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI). She serves on the organizations’ numerous committees, collaborating with other health care professionals and patient advocacy groups to improve quality of life and advance understanding of families living with the challenges of food allergies.

From pediatric weight gains and losses to restricted diets for food allergy and disease management, she does not believe there is a one-size-fits-all answer for success. She will work to find the best balance of meeting nutritional needs with lifestyle demands and ensure collaboration with other members of the care team.

Stressful Mealtimes and Misbehavior

Published by Cuyler Romeo, MOT, OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC on Jan 31, 2023

Imagine sitting your infant down in the highchair for the first time to try solids. As you film the moment, your baby puckers his lips, spits out the puree and turns his head. Mealtime doesn’t improve with time. Instead, food refusal becomes more intense with every meal.

While your friends’ children are happily gumming puffed kale at the park, you can’t imagine offering food in public. You feel exhausted and isolated.

If your family has experienced difficult mealtimes, you’re not alone. I have been honored to support hundreds of families on their PFD journey as an occupational therapist and feeding specialist. Yes, for some children food refusal is a naturally occurring developmental stage, but for others it’s a sign of pediatric feeding disorder (PFD).

Mealtime Behavior Is Communication

All behavior is communication. Children’s communication skills develop over time, and many children are not fully equipped to manage intense emotions mealtimes can evoke. A child may use actions such as leaving the table or display strong emotions such as crying and screaming when their first attempts at communication aren’t heard.

Miscommunication and misinterpretation of communication behaviors can be exhausting for both the parent and the child. Mealtime stress signs may look like:

- Pursed lips

- Head turning

- Throwing food

- Leaving the table

- Gagging

- Retching

- Vomiting

- Screaming

- Tantruming

- Hitting

Causes of stressful behaviors at mealtime

While mealtime behaviors may look similar to families who are struggling to nourish their child, the reasoning behind the communication can vary. Children don’t want to eat and are afraid to eat for many reasons. Some conditions that can cause mealtime stress include the following:

- Food allergies

- Constipation

- Sensory sensitivities

- A structural or anatomical issue in the gastrointestinal tract or esophagus

- Alternate interpretations of food and food properties

- Medical complications in the lungs, heart or brain

- Pediatric feeding disorder (PFD)

Siblings of children with mealtime stress also may be impacted. Research shows that families with one child who struggles during meals are more likely to have multiple children who do.

How to improve your child’s behavior during meals

The underlying reason for your child’s stress behaviors during meals will help you determine your next steps. For example, if your child has a developmental delay or is neurodivergent, they may have more difficulty communicating their needs. They may need support to communicate without extreme stress.

Children who have a physical condition impeding their ability to eat may need support addressing the physical issue before they feel confident eating new or more complex foods.

Whatever the etiology (cause), it’s important to first ask, “What is my child communicating?” Acknowledge their feelings. Never force your child to eat. Seek support. Speak with your child’s pediatrician and share your concerns. Children who are struggling to eat can and do make progress with proper support.

Get help for stressful mealtimes and behavior concerns

Children learn to eat over time. As they grow and develop, their bodies support new feeding and eating skills. By the time a child is five, they will have mastered most oral-motor skills needed to eat a varied and textured diet. But the adventure of learning to eat new foods never ends.

Negative mealtime behaviors during these developmental years can be devastating to any family. Mealtimes should be positive, safe and enjoyable. If you dread mealtimes, this compounding stress can impact other areas of your parent-child relationship. In extreme cases, it can impact every interaction.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Talk to your doctor if you’re feeling stressed about feeding or are concerned your child is not getting good nutrition.

Prepare for this conversation by taking Feeding Matter’s Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire© (ICFQ) and print out or email the results to your pediatrician. This educational tool highlights red flags and builds a more concrete picture of your child’s feeding behaviors.

You may also find it helpful to bring a mealtime record of what, when and how your child eats. A short mealtime video also can be useful to share with your pediatrician.

Your doctor can help rule out medical complications and connect you with other professionals, such as occupational therapists and speech language pathologists with specialized training in feeding. These professionals will help you develop and embed new strategies and behaviors into your family’s daily routines.

The skills needed for safe and pleasurable mealtimes take time to develop. Your therapist should partner with you to identify strategies that will be safe and successful for your child.

Click here to take Feeding Matter’s ICFQ. Find a feeding specialist in your area by visiting Feeding Matters’ Provider Directory. Cuyler Romeo is Director of Strategic Initiatives at Feeding Matters and a clinician at Banner-University Medical Center’s NICU.

Picky Eating: Just a phase or cause for greater concern?

Published by Cuyler Romeo, M.O.T., OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC on Jan 30, 2023

How to know if your child will outgrow picky eating. Plus, how to survive mealtimes with the pickiest palates.

From birth, the majority of time you spend with your infants and young children revolves around food. Children eat a minimum of six times a day. It takes hours to prepare food, feed kids and clean up.

This means that when feeding becomes a challenge, parents can feel like a failure. That was the case for Natalie Peterson, mom of Easton.

When Natalie introduced Easton to solid foods at 4.5 months, she immediately knew something was off. “How he reacted felt different. I brushed it off initially but I think deep down in my gut, that mom instinct knew something was different.”

They tried again and ran into that same reaction. Easton pushed the food away, refused it and even became angry. “It was incredibly isolating. It felt like we had failed him.”

Easton was the first child in the U.S. to be diagnosed with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD).

And Natalie certainly wasn’t the only parent to feel anxiety, frustration and shame over picky eating.

How common is picky eating?

Picky eating is a common disorder during childhood. According to Dr. Kay Toomey, pediatric psychologist and member of Feeding Matters, a variety of studies across the world suggest that approximately one-fourth to one-third of children on average will struggle with some type of feeding and/or growth issue in their first decade.

Picky eating can look similar, but the causes vary. Many toddlers experience a phase of picky eating when they need fewer calories than during months when they were growing faster. That decrease in appetite coupled with their curiosity about boundaries can lead to fussy eating.

It’s when this persists or becomes more extreme that picky eating could be a sign of another underlying condition, such as pediatric feeding disorder (PFD).

What is considered picky eating?

According to Dr. Toomey, the operational definition of picky eating is children who demonstrate either transient or more extended challenges (up to 2 years duration). She outlined the following feeding and eating patterns in a presentation for Feeding Matters:

- Strong preferences

- Limited variety

- A restricted number of foods they will eat.

- Avoiding new foods

- Refusing the “right” foods or the “right” amounts

- Getting more upset than peers

- Requiring a special meal by their parents

- May eat differently in different contexts

How can I help my child with picky eating?

While many children will be picky eaters in spite of parents’ best efforts, there are a few ways to encourage children to eat better.

Following are a few ideas you can try if you’re experiencing stressful mealtimes:

Establish a mealtime routine. Children find comfort and confidence in a predictable routine. This will depend on the needs of your family. There’s no right answer.

Set up loving, appropriate boundaries. I don’t expect a toddler to stay seated at the table for 30 minutes, but I would expect a two year old to eat at the table for 10 minutes instead of taking a bite from the table and running around. If your child is on the autism spectrum, this may not be an appropriate expectation.

Harness the power of hunger. You’re more likely to have successful mealtimes if your kids come to the table hungry. Having a predictable schedule will help.

Make meal time social. Eating with your child, enjoying foods together and modeling appropriate mealtime behavior can help.

Limit the introduction to new foods. New foods are an important way to teach your child about healthy eating. Introduce something new together with something familiar to help your child acclimate.

How long does picky eating last?

Among children who are picky eaters, only about one-third to one-half will outgrow their picky eating within two to three years. Three to 10 percent of infants and children have significant, persistent feeding and/or growth problems over time. These are the children who have pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) and need feeding treatment.

When should I be worried about picky eating?

While picky eating is a common behavior among children, extreme picky eating can lead to nutrient deficiencies or poor growth.

Extreme picky eating is a sign of PFD if a child displays some of the following characteristics:

- Extreme food selectivity: based on texture, color and taste

- Food refusal: gagging, vomiting, hitting, crying

- Limited appetite

- Poor weight or failure to gain weight

- Delayed or dysfunctional eating skills

- Disruptive mealtime behavior

- Eats differently in different environments

- Negatively impacts family functioning

Children with PFD need medical intervention to manage the diagnosis. When a child isn’t eating or drinking the quantity or the variety they need to grow and be healthy, it’s not just because they are being “fussy.” There is usually an underlying reason. Talk to your pediatrician about PFD and check out our family roadmap for support.

Cuyler Romeo is director of strategic initiatives at Feeding Matters and a clinician at Banner-University Medical Center’s NICU.

Premature births on the rise, leading to more pediatric feeding disorders

Published by Feeding Matters on Jan 24, 2023

Here’s what you need to know about the stats on premature births in the U.S., its causes and what we can do about it.

For most families of babies in the NICU, a premature birth comes as a total surprise. That’s because nearly 90 percent of babies in the U.S. are born at gestation, after 37 weeks. But an increasing number of newborns are born prematurely, according to the March of Dimes 2022 Report Card, released in November.

A rising rate of premature births results in an increasing number of babies with feeding issues. Those children who develop long-term feeding issues are at risk of having a pediatric feeding disorder, or PFD.

With a rate of 10.4-10.7 percent of babies born prior to 37 weeks in the U.S. in 2021, the March of Dimes gave an abysmal preterm birth grade of D+. It’s a rate that’s .4 percent higher than the previous year and the highest recorded rate since 2007.

Globally, the rate of preterm birth ranges from 5 to 18 percent of babies born, according to the W.H.O.

The number of weeks babies are born prior to full term and the newborn’s health will determine how long families spend waiting for their babies’ release from the NICU. In an average week in the U.S., nearly 70,000 babies are born. Over 7,000 of them are premature.

Depending on how premature a baby is and problems that may have occurred during their stay in the NICU, most of those babies eventually go on to reach all the milestones of their full-term peers. But this unexpected start is distressing for parents. The biggest challenge for most of the babies is feeding.

NICU staff spend most of their time supporting preterm babies’ nutrition needs, says Dr. Matt Abrams, a neonatologist with Arizona Neonatology at HonorHealth Scottsdale Shea Medical Center. “Feeding difficulty is one of the most common and challenging things we deal with in the NICU. Although people think of preterm babies as having breathing issues, most of the time in the NICU, we spend on nutrition and transitioning to oral feedings.”

The duration of a preemie’s feeding challenges is inversely related to their gestational age. The more pre-term the baby, the more likely they are to take longer to mature. Upon release from the NICU, Dr. Abrams says most of these babies will start to eat normally after a few weeks at home. But some of them will continue to struggle with feeding challenges.

The annual prevalence of PFD in the United States is between 1:23 and 1:37 children under the age of 5. This is higher than other more well-known childhood conditions such as autism (1:54) and cerebral palsy (1:323). Not all children diagnosed with PFD were once preemies, but many of them were.

Causes of preterm births in the U.S.

There are several variables that determine whether or not a baby is born prematurely. These include the following:

- The age and health of the mother

- Contraction of COVID-19 while pregnant

- Obesity and hypertension

- Multiple gestation

- Proximity to a hospital

- Race

- Poverty

- Access to prenatal care

- Smoking/drinking/drug use

Among other contributing factors such as access to prenatal care, Dr. Abrams sees fertility treatment as a key reason for more premature births. “Some places are not being judicious about how many embryos they’re implanting, which leads to higher rates of multiple gestations and therefore increases risk of premature birth,” says Dr. Abrams.

Whatever the cause, an early delivery is a challenge and a shock for parents. This was the case for Paula Benzing, a mom of three in Mesa, Arizona.

Paula visited her doctor for stomach pain, indigestion and heartburn. These symptoms are common in pregnancy, but Paula’s case was severe. Her doctor ordered blood work, and she was diagnosed with HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count.

Paula had a cesarean section right away, at 28 weeks. Her son, Isaac, who’s now 13, was in the NICU for 3.5 months. Much of that time, and for months afterward, was spent on feeding therapy and bottle therapy.

Paula’s second child was born at term. With her third, 6-year-old Penny, Paula once again had to deliver at 28 weeks. Penny needed even more feeding support than Isaac. She came home from the NICU with a feeding tube, which was replaced by a g-tube at six months.

Paula’s day revolved around feeding Penny, all while chasing a two-year-old toddler. Every three hours she’d thicken formula to attempt to feed Penny orally – knowing she wasn’t likely to take it. She’d toss out that formula and instead mix a thinner version for the g-tube instead. “No matter how slow we did it, most of the time she’d throw up. I was a big ball of stress,” says Paula.

Dr. Abrams sees countless anxious parents in the NICU who stress over their babies’ feeding progress. “Eating is social, so it’s very distressing to families when kids can’t do that. At the same time, it’s not very tangible. When babies are on a ventilator or they have something more concrete, families cope much better than when their baby is totally healthy but having feeding issues. They must be patient to see how things evolve over time.”

The increase in preterm births in the U.S. means more and more families are having to be patient. But, not all families are affected equally.

Race and geography matter for maternal health

In the March of Dimes report card, some states scored worse than others. Nine states and one territory, including seven states in the Southeastern United States, received a grade of F. Only one state, Vermont, received a A- state-level preterm birth rate, with the lowest preterm birth rate at 8 percent.

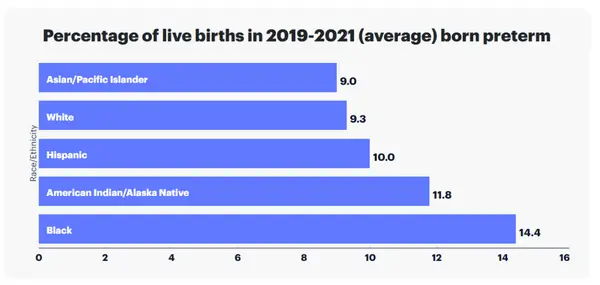

Preterm birth rate also varied by race and ethnicity in the United States. Preterm birth rate among Black women is 52 percent higher than the rate among all other women, according to the report.

Within states, the likelihood of preterm birth varies as well, depending on location, economics and ethnicity.

Impact preterm birth has on children and families

A preterm birth is often stressful for parents during their baby’s stay in the NICU. Juggling work and home responsibilities compounds that anxiety. Preemies are typically sent home with overwhelming and time consuming care instructions that can include multiple care appointments.

Parents of children who require longer support or have additional diagnosis, like pediatric feeding disorder, carry an even heavier burden.

According to a nationwide survey of insured families conducted by Feeding Matters:

- 76% of respondents reported that PFD results in at least a moderate financial burden for their family

- 33% of respondents had to leave full-time employment

- 23% turned down a job offer/raise in pay/more hours per week

- 47% reported depression

Overall, the lifetime average income loss to a family is $125,645.

The stress for a family can be tremendous for the duration of a child’s feeding challenges. Denise Hoffman is a pediatric occupational therapist and clinical assistant professor at Indiana University South Bend. While she was uniquely positioned to support her child who was born prematurely and had feeding issues, she still faced massive challenges. She had the luxury of quitting her job and made breastfeeding her son, Trey, a full time job. She describes feeding him and practicing feeding therapy a 24/7 job. Still, she recalls that he’d only manage to eat an ounce in a feeding.

Besides the time commitment this requires, the stress takes its toll. “As a mother your instinct is to feed your kid, and when you can’t, you feel like a failure,” she says.

Denise was grateful that she could stay home with her son and his older brother. She also had help from family. Many Americans facing similar struggles aren’t as fortunate.

How the U.S. can decrease the rate of preterm births

Prenatal care helps prevent preterm births. But Dr. Matt Abrams argues intervention needs to take place even before pregnancy.

“I think the work must be done before pregnancy by reducing complications related to obesity, diabetes and hypertension and by having fertility treatment that is judicious about who is a good candidate and how many embryos are implanted. Once you’re pregnant, there are few ways to reduce preterm birth other than good prenatal care. In rural areas of the country, it means increasing access to telemedicine.”

The March of Dimes advocates for much-needed legislation and funding that can improve maternal and infant health outcomes. Click here to read about their campaign #BlanketforChange to advocate for health equity for moms and babies.

They say it takes a village to raise a child. Turns out, it takes the will of a whole country to support newborns and their families.

Feeding Matters is the first organization in the world uniting families, healthcare professionals, and the broader community to improve the system of care for children with pediatric feeding disorder through advocacy, education, support, and research.