Author: Jalenna Francois

Accurately Diagnosing PFD and ARFID: Why Misdiagnosis Can Do More Harm Than Good

Published by Jaclyn Pederson, MHI on Apr 21, 2023

I recently heard about a distraught mother of an eight-year-old, whose daughter spent time in an eating disorder clinic. She was diagnosed with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), which is often described as extreme picky eating.

After completing the program, her child showed no improvement and even developed more anxiety around eating. Minutes into the conversation, it was clear that this child most likely had undiagnosed pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). An effective assessment and treatment plan must address more than psychiatric and behavior therapy for any child who has been identified as having concerns with feeding.

As CEO of Feeding Matters, I hear these stories regularly.

In the two years since PFD became an official ICD diagnostic code, I’ve seen hundreds of families in the U.S. and around the globe become more informed and able to access better care for their children. Naming the issue that has many symptoms and requires a multidisciplinary approach has given families tremendous relief and support.

But, our work is far from over.

What happens when PFD is mistaken for an eating disorder

Children as young as one are being diagnosed with ARFID when they actually have PFD. In plain terms, this means children with a medical and multidisciplinary feeding disorder are instead diagnosed as having a psychiatric condition.

The actual cause of children’s limited intake or picky eating is sometimes overlooked. It’s nearly impossible to resolve a mental or behavioral eating issue without first looking into the other domains that contribute to eating function, including medical and feeding skills.

I’ve seen with my infant how eating is a learned behavior. My baby has a cow’s milk protein allergy and challenges with his suck and anatomy. Once we identified his issues, we switched formulas and found a better bottle for his anatomy. Even then, it still took a month for him to develop the necessary feeding skills to consume greater than one ounce per feeding. My child only had a feeding challenge, and was not diagnosed with PFD. Still, this shows how a holistic assessment and treatment plan that considers the interplay of the four domains of PFD allows for targeted interventions that match each child’s unique needs. With early identification and treatment of medical and feeding skill dysfunction, the hope is that the long term psychosocial impact can be reduced.

The longer feeding challenges go untreated, the greater the psycho-social impact. As children get older, psychological difficulties become the primary drive for feeding dysfunction and the problem evolves from a developmental one to a mental health condition.

Why PFD is often misdiagnosed as ARFID

ARFID is a mental health diagnosis for children who have the following:

- Significant weight loss (or failure to achieve expected weight gain or faltering growth)

- Marked interference with psychosocial functioning

- Nutritional risk or deficiency

- No coincident body image problems

- Disturbance is not due to a medical condition

PFD is a multidisciplinary diagnosis that includes feeding dysfunction in any one or several of four domains:

- Medical

- Nutrition

- Feeding skill

- Psychosocial

There are many reasons PFD is mistaken for ARFID. The main reason is that PFD is a much newer and less widely-known diagnosis. We facilitated the publication of a paper that provided a consensus framework of PFD in 2019. PFD became an ICD code in the U.S. in 2021, over a decade after ARFID. PFD has an international impact because the diagnosis was centered around the international classification of functional disability and health. The PFD diagnosis and subsequent ICD code use the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework. This framework allows the international medical community to evaluate the functional impact feeding has on a child’s activities. It also promotes a multidisciplinary, holistic assessment of how the four domains, medical, nutrition, feeding skill, and psychosocial, interconnect. This ensures the root cause of a child’s feeding challenges are identified.

However, psychologists and practitioners in the eating disorder world tend to know only about ARFID.

Information available on social media is another reason PFD is misdiagnosed as ARFID. Parents concerned about a child’s picky eating can go down a rabbit hole of online information that’s more likely to point to ARFID as online it gets inaccurately labeled as “severe picky eating.” The unfortunate piece to this is that in these conversations about ARFID and severe picky eating, social media presents a misleading picture that fails to take into consideration the medical or feeding skill reasons why a child might have trouble feeding.

Understanding PFD and ARFID

PFD and ARFID in children and young adults share symptoms and behaviors. The child does not eat as much or in a manner expected for a child’s age. The cause and the treatment for this behavior is what varies. Some children with PFD go on to develop ARFID.

A classic case of ARFID is someone with no history of feeding problems before its onset. For example, a child has a choking incident and then is afraid to eat. Another example would be a child with no feeding skills issues but is described as having odd eating habits.

A child with undiagnosed PFD will have a history of feeding issues. These can include any combination of issues, including: allergies, reflux, challenges with bottle feeding, and trouble transitioning to solids.

Treatment for a feeding disorder differs from an eating disorder. For PFD, a clinician will determine if the child is safe to eat. Does he have the skills to chew and swallow? Are there allergies that may be present?

When a child is treated only for ARFID, they’re entering a mental health pathway that can often be difficult to assess and identify if there are other domains present.

Education is vital to improve diagnoses of PFD and ARFID

Education is the key to providing better treatment for children with PFD and ARFID.

We at Feeding Matters are working with clinical experts in the field to help clarify how to determine the correct diagnosis and treatment plan for those who have either PFD or ARFID – or both.

Our goal is that clinicians will better understand both diagnoses so that more patients can be identified earlier and access effective treatment.

Parents need to be aware that PFD can sometimes be misdiagnosed as ARFID or that if PFD goes undiagnosed it can become a more severe ARFID. This knowledge will help more families get treatment from clinicians who understand how to treat PFD and how the two diagnoses overlap.

The earlier we help more families identify the true issue, the more likely we will ensure they get the help they need.

Are you looking for more information? Visit Feeding Matters’ resource page: PFD and ARFID.

The Power of Trauma Informed Care for Children with Pediatric Feeding Disorders

Published by Feeding Matters on Apr 05, 2023

Of all the clinical appointments for 15-year-old Maya Roberto over the years, one stands out. Instead of catatonically going through the motions of her echocardiogram, Maya interacted with her cardiologist, even asking questions. Her mother, Dr. Anka Roberto, recalls how shocked she and her doctor were as Maya actively engaged with her cardiologist for the first time.

Noting that his patient, who was five years old at the time, was much more lively, the physician asked what had changed. Roberto, DNP, MPH, APRN, PMHNP-BC told him, she was in trauma therapy and just had an Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) session to help her work through her medical trauma.

The doctor had never heard of it, and was pleasantly surprised with its efficacy.

Today, Roberto uses EMDR to help heal her pediatric patients from trauma as a private practice clinician.

Roberto’s years as a NICU nurse and mother of a child with complex congenital heart defects prepared her for a career in trauma-informed care as an advanced practice nurse. She’s seen personally and professionally how much treating a patient’s trauma as part of the continuum of care can make a difference.

Since birth, Maya’s journey has included multiple open heart surgeries, years of feeding therapy and an NG tube. Roberto knows firsthand how traumatic medical and feeding interventions can have a lasting impact. For children with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD), considering and treating medical trauma can go a long way toward healing children.

Trauma-informed care offers a comprehensive approach that considers emotional and mental well-being to help children and their families affected by PFD. Understanding the impact of trauma on the body and how to navigate it allows families to access an effective care modality.

Defining trauma

Trauma varies for everyone. One major incident or many minor insults can cause trauma. Two people experiencing the same situation can respond entirely differently. One can move forward, while the other carries a lasting physical and emotional imprint. “When I think about trauma, it’s more of an adversity,” says Roberto. “We could have a big trauma, or we can have little things that add up to carry the same weight of a big trauma.”

What matters is how trauma affects the brain and body.

The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study is one of the most comprehensive investigations into the lasting effects of childhood trauma. The longitudinal study showed that early adversity could significantly impact future physical, social and emotional health – as well as lead to early mortality rates.

The pandemic further raised awareness of how trauma can affect mental and physical health.

How the body reacts to trauma

Trauma can profoundly affect the body. Potentially traumatic experiences trigger the body’s “fight or flight” response. In this state, the heart rate increases, and respiration speeds up as the sympathetic nervous system prepares to defend against danger.

The disruption of hormones and enzymes caused by the experience can lead to difficulty regulating temperature, breathing and digestion. The gastric emptying system turns off. It causes constipation, loss of appetite, and/or motility (muscles in the wall of the gut) issues.

“It’s like the fire alarm in the house is going off,” says Roberto. When this happens, the parasympathetic system, sometimes called the “rest and digest” system, stops working.

These acute responses can make an imprint that has long-term effects. Families of children with PFD can mitigate the impact of trauma with support and care. “Trauma leaves a mark, but it’s up to us to find those who can help us get out of being stuck in the triggered cycle,” says Roberto

Understanding trauma-informed care for children with PFD

Trauma-informed care is an approach to support those who have had adverse experiences during their lifetime. Unlike traditional forms of care, which may not be sensitive to traumatic experiences, trauma-informed care recognizes the impact of trauma on an individual’s behavior, thoughts and emotions. The goal is to create a safe space for healing and recovery.Trauma-informed care involves four key components, known as the “Four R’s:

- Realizing how trauma can affect an individual

- Recognizing signs an individual has experienced trauma

- Responding effectively with appropriate interventions

- Resisting re-traumatization by promoting safety, trust, empowerment and collaboration

Understanding these components is essential to effectively support children with PFD, who may be dealing with the long-term effects of traumatic experiences.

Trauma can disrupt eating patterns by causing fear or anxiety around food, leading to refusal or avoidance behaviors. This compounds feeding issues children with PFD already experience.

For children with PFD, trauma-informed care offers a safe way to explore emotions while helping them build positive relationships around eating.

How to navigate the impact of feeding trauma

The effects of trauma on children with PFD can be challenging. What’s traumatic to one child may barely register for another. And the traumatic experience often isn’t even something the child can recall.

This is why it’s crucial to understand each child’s experience, recognize triggers and provide emotional support. Therapeutic interventions such as EMDR can help children reprocess past traumas without needing to talk about them. In her practice, Roberto uses a sand tray and play therapy to help children process previous experiences and feelings.

“They may not have verbal recall and a story to tell, but they remember feeling a certain way,” she says.

A child’s visit to a doctor’s office, for example, can trigger a panic attack because they don’t want to lie on the table, says Roberto. “It’s really because of this unprocessed adversity, which for many people may come from a place of not having control.”

With EMDR, she helps children uncouple the emotional tenacity from that memory.

Benefits of trauma-informed care for children with PFD

Trauma-informed care provides a safe space for families to build trust and better understand how to support their children. Trauma-informed care allows children to explore the experiences that triggered their trauma and develop improved emotional regulation skills. It can also lead to an improved appetite and a willingness to try new foods.

When children get emotional support, they can better articulate their needs to their parents and healthcare team. A therapist can help a child develop practical communication skills and problem-solving techniques. With practice and guidance, these tools allow children facing medical trauma to cope more effectively in difficult situations.

3 ways to support children with feeding trauma

Finding the right resources for trauma-informed care can be challenging, but more resources are developing with a heightened awareness of trauma’s impact.

Focus on the whole family

Roberto says supporting the entire family is key to helping children heal from traumatic events. “Families are like a tree, so if one limb is struggling, the others will start to wither as well.”

Give kids time

Children with medical complications react to stress in the same instinctual way as anyone who senses physical danger. Anyone who’s had to submit their child to medical testing has likely witnessed the fight, flight or freeze response. Roberto recommends slowing down in those moments. “Listen to your kids and give them the time to get there. It’s not about our agenda, as parents or as clinicians. It needs to be about the child’s agenda and providing them with the support they need in the moment.”

Get outside support

Talk to your child’s doctor or pediatrician about what type of care is available in your area and look for mental health providers who specialize in this trauma-informed therapy.

Online resources can also be helpful when seeking out trauma-informed care. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network offers comprehensive information geared toward helping families affected by traumatic events.

Finally, it’s important to remember that although trauma can be difficult, it can be an opportunity to move forward and break the trigger cycle. Roberto says, “We all have our experiences, but we don’t have to let them define us or limit our future possibilities.”

By understanding the trauma children with PFD can experience and working through it with compassion, children can regain control over their lives and reach their full potential.

Anka Roberto, DNP, MPH, APRN, PMHNP-BC an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina Wilmington and has authored book chapters and numerous publications on trauma and resilience. In her private practice, Holistic Healing, PLLC, she provides functional psychiatry care and EMDR therapy to target and reprocess negative life experiences across the lifespan.

Roberto is the keynote speaker at the 10th Annual International PFD Conference on April 13-14. Click here to learn more and register.

What the IPFDC has to offer…

Published by Feeding Matters on Mar 30, 2023

“What I like most about the Feeding Matters conference is that it really has something for people who are at that advanced level. For entry level, intermediate level, or advanced level clinicians, the Feeding Matters conference has something for everyone. I learn something every year.

When I am in a pool of Feeding Matters occupational therapists and speech therapists, I am soaking in all the knowledge I can get. There are so many layers to pediatric feeding disorder and these conferences have something to offer for even the advanced clinician.”

-Kate Barlow, OTD, MS, OTR/L

e

What I learned working with a pediatric dietitian

Published by Jalenna Francois on Mar 29, 2023

March is National Nutrition Month! Read along to meet Feeding Matters staff member Jalenna Francois and her experience working with a pediatric dietitian.

Hi! My name is Jalenna Francois. I am the Communications and Awareness Specialist at Feeding Matters. My daughter Sophie was born two years ago (this Friday is her birthday — happy birthday, Soph!). We struggled with feeding pretty immediately after she was born. With the help of a tongue and lip tie revision, lactation consultant, osteopathic manipulation, and the removal of milk from Sophie’s diet, we made huge improvements. I am forever grateful for the early intervention Sophie received, which occurred in part because I’ve worked for Feeding Matters for nearly ten years and know the early signs of a potential pediatric feeding disorder.

Hi! My name is Jalenna Francois. I am the Communications and Awareness Specialist at Feeding Matters. My daughter Sophie was born two years ago (this Friday is her birthday — happy birthday, Soph!). We struggled with feeding pretty immediately after she was born. With the help of a tongue and lip tie revision, lactation consultant, osteopathic manipulation, and the removal of milk from Sophie’s diet, we made huge improvements. I am forever grateful for the early intervention Sophie received, which occurred in part because I’ve worked for Feeding Matters for nearly ten years and know the early signs of a potential pediatric feeding disorder.

As she grew, we discovered she had IgE-Mediated food allergies (what you think of when you hear about food allergies, for Sophie they typically present as hives and wheezing) and FPIES (Food Protein Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome, which presents as vomiting several hours after ingestion of a trigger food). Both of these are comorbid conditions for pediatric feeding disorder.

Our family has been on a long feeding journey over the past two years, and it was changed forever because of our work with a pediatric dietitian. I have learned many lessons from these regular visits with Sophie’s dietitian:

- Nutrition is a lot more than what’s on our plates.

While I did learn about nutrients, how to pair foods, and substitutions to get Sophie what she needed from her limited diet, I also learned that there is a lot more that goes into feeding my family than how many servings of vegetables we get. I learned to acknowledge and set aside the cultural expectations, personal expectations, and the fear and anxiety which wasn’t helping us meet our needs. I learned to meet Sophie where she was with eating. - Meals carry a lot of emotion!

It is so easy to get overwhelmed, anxious, and stressed about feeding my family. Can (or will) Sophie safely eat this? Did she eat enough? Are we eating enough variety? Wow, allergic reactions are scary! As I began to recognize the power this anxiety held over me, I could see it trickling down to my kids as well. At the suggestion of our dietitian, we now check in on emotions before we sit down at the table. There are nights where we can jump right in to eating, but other nights, we need a family story time to connect, take off the pressure, and enjoy just being together before we eat. Creating this feeling of connection and safety before we get to the table has helped to reduce the immediate ‘YUCK’ my 4-year old likes to react with when she sees the foods being offered. - Lead by example.

For me, this has looked like taking intentional time to feed myself food that is nourishing and enjoyable. I don’t let my kids skip meals, and I am trying to treat myself the same way. I have learned to incorporate all foods I enjoy without guilt, in a balanced way. Caring for myself will only benefit my children as well. - Give yourself grace. Feeding is a journey, and progress is more important than perfection.

Not every meal is going to go perfectly, not every food is going to be accepted, even after 100 exposures. Having patience with myself and my children as we learn together is building the trust we all need to make progress. - The power of having someone in your corner.

Having someone to talk over meal plans and strategies for food introductions and substitutions was huge. But what I remember from the beginning of our journey with our dietitian was having someone to help me see hope when our feeding experiences felt overwhelming, never-ending, or unfair. Having someone who gets it and is able to help you see the possibilities ahead is a game changer. (Pro tip: Looking for someone to be in your corner? Check out the Feeding Matters Power of Two program.)

By now, I’m sure you can tell that my dietitian is awesome! Not only is she a great dietitian, she shares her extensive knowledge on her Instagram and blog so that everyone can learn like I have. She also recently became a Feeding Matters board member, which is just one way she is as a champion for children with PFD.

By now, I’m sure you can tell that my dietitian is awesome! Not only is she a great dietitian, she shares her extensive knowledge on her Instagram and blog so that everyone can learn like I have. She also recently became a Feeding Matters board member, which is just one way she is as a champion for children with PFD.

As we celebrate Sophie’s second birthday this week, I am so proud of the progress our family has made together. I never imagined we would make it to where we are today, and I look forward to seeing where the rest of our journey takes us, with our dietitian by our side.

Collaboration with Arizona Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program

Published by Feeding Matters on Mar 25, 2023

Recently, Feeding Matters has been working closely with the Arizona Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program. WIC is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) which provides US federal grants to states for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age 5 who are found to be at nutritional risk.

We are excited to share that as a result of our relationship with Arizona WIC, the nutrition coordinators and directors, who are the front line folks supporting families eligible for this program, have been trained on pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). Specifically, Arizona WIC coordinators and directors are trained on the PFD Co-Morbidity and WIC Risk Code spreadsheet so that any time one of them uses one of the codes associated with PFD, they will be prompted to refer the family to Feeding Matters and our Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire. For example, if a child eligible for Arizona WIC is noted as having a genetic or congenital condition, they would be referred to Feeding Matters, specifically to our questionnaire to dig in deeper on their child’s feeding and have a source of support through us.

“This collaboration between the Arizona WIC Program and Feeding Matters ensures that children who have a known condition that often co-occurs with pediatric feeding disorder are more easily identified, identified quickly, and are referred to Feeding Matters to get the support they need.”

Brittany Howard, MS, RDN, CLC (WIC Nutrition Services Administrator)

The collaboration does not end there. They have also added Feeding Matters as a resource to their online education courses that they offer to all of their staff.

We know that PFD impacts one in 37 children under the age of five in the United States and are confident that this partnership will lead to earlier identification and intervention of children with PFD.

It’s ok to cry

Published by Feeding Matters on Mar 24, 2023

We recently held a contest asking for designs for our PFD Awareness Month merchandise store. We are excited to share our contest winner! This design was created by Madison O’Brien, an Oregon based Speech Pathologist who also has a sibling with a history of a pediatric feeding disorder.

Madison shared her inspiration for the design:

“Parents of children with a Pediatric Feeding Disorder experience high levels of stress and are more likely to develop anxiety and depression than parents of children without feeding difficulties (Rodriguez 2022). So many parents of kids with PFD have expressed to me that they’re barely holding on. I just want them to know they’re not alone and that it’s valid to feel that way.”

Thank you for your design Madison! You can purchase this design, and others, at our merchandise store here.

Reference

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2341287922001922

Pass on the peas; pass the pizza, please

Published by By Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES on

Is your child getting enough nutritional variety? How to know and what to do about it

By Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES

Mass General for Children Pediatric Nutrition Center of Excellence, Center for Feeding and Nutrition

Nutritional variety for children ages 0-5 is extremely important to the growth and development that happens in those early years. That said, it’s normal for young children – especially toddlers – to go through phases of picky eating as they explore their world and assert their independence. In honor of National Nutrition Month this March, read the blog below from expert pediatric dietitian Simona Lourakas of Mass General Hospital for Children to know what to expect when feeding young children and how to ensure they get the nutritional variety they need.

When your baby starts eating solid foods, it’s not uncommon to expect that transition to go well. No matter that the foods are only as exciting as room temperature, smashed peas. Other tots the same age are happily gumming blended foods.

But, as hard as you try, your child refuses to eat many of the foods you offer. Is this a sign of age-appropriate picky eating? Or is it an indicator of a more significant issue?

What is nutrition variety?

Nutritional variety for adults and children means eating foods from all food groups: grains, proteins, dairy, fruit and veggies. There are other calcium fortified foods for those who can’t eat dairy. And many fruits and veggies have a lot of nutrition overlap.

Exposing kids to solids builds up their feeding and oral motor skills. It helps prevent food allergies later on and increases diversity in the gut. For breastfed infants, iron-rich proteins can be an important food group such as iron fortified cereals, beans, leafy vegetables and lean meats.

At around nine months old, a limited variety or quantity of solids will start to impact growth, nutrition and oral-motor skills.

Why nutrition is so crucial for young children ages 0-5

Nutritional variety is critical, affecting every area of children’s growth and development. A study conducted by Feeding America shows that malnourished children:

- Cannot learn as much, as fast, or as well as peers

- Have more social and behavioral problems because they feel bad and have less energy

- Require frequent doctors’ visits

- Are at risk for cognitive development during this critical period of rapid brain growth

The kinds of nutrition, care, stimulation and love children receive during these critical first years of life determine the brain’s architecture and central nervous system. Identifying and treating feeding and nutrition problems are crucial to supporting children’s cognitive, physical, emotional and social development, as well as the caregiver-child relationship.

How to know if your kid is getting enough nutritional variety

Like anything in parenting, there’s a lot of pressure to compare your child’s eating to peers, especially once children enter daycare or preschool. This only adds to the stress parents can already feel around feeding their children and ensuring they get the nutritional variety they need.

Considering the size of your hand to your child’s hand is a good reminder of how small a child’s portions need to be. A portion of protein is only about the size of the child’s palm. A grain serving is the size of a closed fist.

Most children will not eat all five food groups in a meal and maybe not even in a day. Instead, consider what your child eats over the week. They’re likely getting enough nutritional variety if they eat foods from all food groups over that period.

What to do if you’re concerned

Developing a healthy eater is challenging for many parents. Even for children without any feeding issues, this can take time, patience and persistence. Children with food allergies, autism, sensory concerns, premature birth or medical complications will need a more specialized approach to eating.

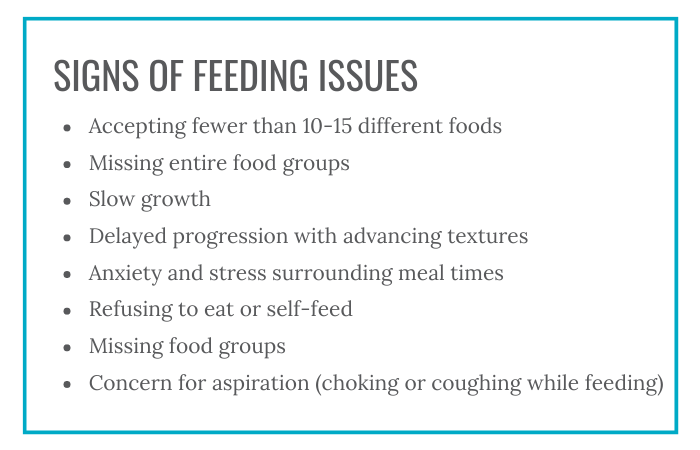

Following are some signs of feeding issues:

- Accepting fewer than 10-15 different foods

- Missing entire food groups

- Slow growth

- Delayed progression with advancing textures

- Anxiety and stress surrounding meal times

- Refusing to eat or self-feed

- Missing food groups

- Concern for aspiration (choking or coughing while feeding)

Speak to your pediatrician if you are concerned about your child’s eating or nutritional variety.

Tips for parents to add nutritional variety to kids’ diets

1. Know that picky eating is normal for toddlers.

It’s normal for toddlers to have food preferences, such as more fruits vs. vegetables, grains and dairy.

2. Consider adding fortified foods or nutritional supplements.

For children who can’t have dairy, some fortified pea or soy milks are a suitable replacement. For children who are missing other food groups, fortified foods like cereals or supplements, like an age-appropriate multivitamin or formula, can make up for some of that missing nutritional variety.

3. Introducing new foods takes time.

It can take offering a food 10 or more times before a child will accept it. Add new foods with nutritional variety together with familiar foods. This will reduce the pressure or forcing your child might feel.

3. Involve your child. Children of all ages can help prepare and choose foods in safe, age-appropriate ways.

4. Allow children to play with new foods.

Food play is a great way to introduce new tastes and textures without making children feel pressured to try it. Some of the new food will often end up in young children’s mouths this way.

5. Avoiding grazing.

After one year, aim for three meals a day, with 1-2 snacks. Offer appropriate amounts of milk. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests 16-24 ounces per day of whole cow’s milk for 1-2 years and 16 ounces per day of low fat milk children 2+ years. Avoid juice. Grazing all day affects appetite at meal times.

Parents are doing their best

When it comes to feeding your child, know that how much your child eats doesn’t define how well you’re parenting. A parent’s job is to provide food and age-appropriate nutritional variety. It’s the child’s job to eat it.

Parents who offer food in the same way to siblings may find that one has feeding difficulties while the others don’t. As hard as it is to keep from comparing children to peers, including siblings, know that feeding issues are complex.

If you’re concerned about your child’s feeding, know you are not alone. Early detection and treatment of pediatric feeding disorder is critical to affected children’s long-term health and well-being. Check out our six-question screening tool on our website and reach out if you need more support.

Simona Lourekas, MS, RD, LDN, CHES is a registered dietitian in Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition at Mass General for Children, a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. She also works with post-acute care rehab Franciscan Children’s.

FROM THE PFD ALLIANCE: A FOCUS ON EDUCATION

Published by Amy Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP on Mar 22, 2023

As we approach our 10th Annual International PFD Conference, I look forward to learning from expert colleagues about new ideas and strategies that we can use in the care of children with PFD. It comforts me knowing that Feeding Matters has worked diligently to offer content that has been both reviewed for bias and is rooted in evidence. This makes me reflect on the current educational landscape and how it has changed over time.

Thinking back to when I first entered the field (and yes, I’m aging myself), sources for educational content were textbooks and hard copies of journal articles, either arriving in my mailbox or checked out by me at the library. Unfortunately, these old-school sources were nearly outdated by the time they entered my hands. In-person conferences were the only method for me to learn what things were at the cutting edge from my peers and scientists in the field.

Learning today has never been easier! Today’s technology affords endless formats and venues from which we receive information. We have access to first-hand information directly from researchers, clinical experts, and parents. We see examples of different disorders and impairments and clinically validated intervention strategies while standing in line for coffee, or even while on a walk.

Unfortunately, access to everything all the time can be overwhelming, and it may be difficult for a learner to navigate material without a good understanding of its strengths and potential weaknesses. It may seem that everyone is an expert and it’s hard to discern that the information being shared may not be objective, evidence-based, and/or appropriately interpreted. It may be difficult to know which sources to prioritize for one’s learning.

What are my best options? Who am I listening to and what is the underlying evidence? For social media, if one source has more followers than another, is it more likely to be correct or validated? Who is vetting the information? Here are a few pitfalls to keep in mind:

- Saying something with confidence and fancy graphics does not make it sound evidence.

- A greater number of followers does not guarantee information is superior to that from a source with fewer followers.

- Be mindful of individuals who discount or contradict what you have learned to be reliable and clinically validated information.

- Conversely, be mindful of individuals who purport that information is accurate because it’s how it has always been done.

- Is the information based on published studies or other peer-reviewed content?

- Is the source only promoting a product?

- Is the source acting in a professional manner that is ethical and considerate of other opinions?

As we continue to navigate our educational options, consider some of the following suggestions:

- Use multiple sources for learning. Maintain a broad diet of information that includes social media, webinars, and in-person meetings. A broad educational repertoire is always best.

- Dig a little deeper into a new source of information. Learn about your favorite vloggers and what their experience may be. What is their profession and their training? What population of children do they see? Know who you are listening to and trusting to contribute to your clinical journey.

- Think critically about what you’re learning. Does it make sense? Does it continue to enhance your knowledge and practice? Does it contradict well-known evidence?

- Rely on your professional organizations to review the current state of information and evidence and provide experienced perspective on how new ideas may fit into established paradigms.

- Advocate that we need pediatric feeding and swallowing taught at the university level to give everyone a foundation.

We, as a community of PFD providers and families, must lift each other and support each other in our learning to advance the field and the lives of children and families with PFD.

Amy L. Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP

Amy L. Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP

PFD Alliance Education Chair

Why clinicians should attend the PFD conference

Published by Brianna Miluk, MS, CCC-SLP, CLC on Mar 08, 2023

The Pediatric Feeding Disorder conference emphasizes kindness, community and communication

The first time I joined the International Pediatric Feeding Disorder (PFD) Conference, I sat alone in my sunny South Carolina office, anticipating a typical academic research virtual presentation that would count for some CEUs.

Instead, what I found was relatable and practical content that I wanted to share with every clinician I knew.

I’ll never forget a particular workshop by Dr. Kay Toomey on Picky Eaters vs. PFD vs. ARFID: Differential Diagnosis Decision Tree. At one point, I got so excited about the presentation that I leaped out of my chair and clapped enthusiastically. Now, anyone who knows me sees that I have a lot of energy, so this wasn’t totally out of character. Still, I’ll admit I looked a little strange in my office, shouting with glee. When my husband came running, I couldn’t resist exclaiming, “THIS IS SO GOOD!”

It’s no exaggeration to say that the first time I attended the Feeding Matters International Pediatric Feeding Disorder virtual conference in 2018, I was hooked.

The conference isn’t just an opportunity to check off your requirements box for ASHA, AOTA or ACCME. It’s a virtual gathering of clinicians and families all motivated by a singular goal: helping more children and families access the care they need for pediatric feeding disorder.

As part of the conference planning committee for 2023, I can attest that our goal for every presentation is to deliver practical takeaways for families and clinicians. This is part of what makes the PFD conference so powerful.

It’s tricky to organize a virtual conference. Besides any potential technical glitches, creating a sense of community and conversation is challenging. But the PFD conference is unlike any other I’ve attended. There’s a sense of kindness, community, and communication that all attendees feel throughout the program.

What clinicians will benefit from the PFD conference

The PFD conference is ideal for any clinician serving children with feeding issues from birth through adulthood. This includes:

- Occupational therapists

- Speech and language pathologists

- Dieticians

- Physicians

Because the program is so family-driven, I even encourage caregivers to attend. Everyone benefits when they learn about different methods and what the research shows.

4 reasons to attend the PFD conference

There are many reasons to take time from your busy clinical schedule to attend the conference. The following are just a few.

Learn practical, innovative interventions and strategies – and how to apply them with families

Like any continuing education, the pediatric feeding disorder conference highlights the latest research and interventions. This conference is different because the presenters go one step further to show how to apply that information to our day-to-day work. Every course I attended focused on how an intervention is only as good as it is for an individual family. As a speech therapist, I see how this mindset matters. I can have all the research in the world at my fingertips, but it’s not practical if none of it works for the family in front of me. That clear focus across all the workshops means that at the PFD conference, I can walk away with strategies to apply immediately.

Build connections across fields

Making friends and forging new professional relationships is not usually a goal for a virtual conference, but that’s what happened at the PFD conference. The chat is active, and the people are friendly. I’ve made real-life friendships with clinicians in my area. I would never have met them outside of that opportunity.

When providers of various backgrounds work together, patients benefit.

Become a stronger advocate for clients

The PFD conference has helped me grow both in my practice and as a patient advocate. I’ve gained knowledge and leadership skills that help me articulate what my clients need, especially when working with other clinicians who aren’t as familiar with PFD and the diagnostic code.

Each year, I leave with a strong call to action to continue advocating for children with PFD and their families. The conference empowers clinicians to hold each other accountable for higher standards of care.

Raise awareness of how trauma-informed care relates to PFD

I’m most excited about this year’s conference’s keynote address, Healing Feeding Trauma: It takes a village, from Dr. Anka Roberto DNP, MSN-MPH, APRN, PMHNP-BC. Bridging the gap in education on how trauma-informed care is essential to treatment for PFD is so important. Spotlighting this topic as the keynote underscores how important it is to heal feeding trauma for the child and the entire family unit.

Every year I’ve attended the PFD conference is better than the last. I don’t doubt that this year’s 10th annual conference will be the best one yet. See you at the conference!

The 10th annual international PFD virtual conference is April 13-15. Register, see our schedule and speaker roster and more here.

Brianna (Bri) Miluk is a speech-language pathologist and certified lactation counselor in Greenville, South Carolina. She has a clinical focus on pediatric feeding and swallowing in infant and medically complex patient populations. Bri is an advocate for information literacy, evidence-based practice, and trauma-informed care, including neurodiversity-affirming practices. She is also an Instructor for Pennsylvania Western University. She is a PhD student with a research focus on disseminating or research and misinformation in speech language pathology on social media. She hosts the podcast, The Feeding Pod, and teaches the Pediatric Feeding Mentorship Group course. Follow her on Instagram @pediatricfeedingslp.

Parents’ Guide to Helping Your Baby with Slow Growth: Expert Tips and Advice

Published by Mary Anthony, RN on Mar 03, 2023

Pediatric developmental nurse answers questions on slow growth, lack of growth, weight loss

Expectant parents have all sorts of worries leading up to birth, but feeding your baby and slow growth usually aren’t among them. You assume your newborn will suck from the breast or a bottle. When this doesn’t happen easily, bringing home your baby becomes more complicated.

Babies with slow growth, lack of growth or weight loss typically spent some time in the NICU and may even have a tube to supplement feeding.

In many cases I see, parents are sent home without a feeding plan when their babies are discharged.

What causes slow growth, lack of growth or weight loss in infants

There are many reasons infants experience slow growth, lack of growth or weight loss, which can all sometimes be called failure to thrive. Common ones include:- Premature birth

- Trouble latching

- Reflux

- Medical conditions

I’ve seen countless overwhelmed parents caring for newborns who require extra support for feeding. This is challenging in the best of circumstances when parents have a lot of help from family and friends.

It’s nearly impossible for those with fewer resources.

Families need more support

First time parents are inundated with an overwhelming amount of new information. The learning curve for managing a newborn is significantly compounded when the baby has slow growth, a lack of growth or weight loss. This is often called “failure to thrive.”

Parents of these babies often lack all the tools and information they need to help their babies grow and thrive.

It’s my job in Maricopa County, Arizona to fill that gap.

In one telehealth visit, I spoke to a mom whose baby was born at 24 weeks and had an NG-tube. Through our conversation, I learned she had a formula prescription, but she didn’t have a feeding plan.

The mom didn’t know when to increase the amount of formula, when to offer oral feedings or even when to visit a gastroenterologist (GI). I helped her develop a plan and get an appointment. Her experience wasn’t unusual.

When a baby leaves the hospital with a feeding tube or after treatment for weight loss or slow growth, hospital doctors assume that pediatricians will ensure the baby’s feeding needs are met. Pediatricians assume the GI manages the feeding plan. And the GI often doesn’t see the baby for months.

More support for these families can make the transition to home easier.

In Arizona, any baby who’s in the NICU for five days or more is eligible for support from a pediatric developmental nurse for up to three years. This includes at least four visits a year in the first year.

I’ve seen firsthand how support is crucial for overwhelmed parents, especially within 14 days of discharge.

Customized care to help babies with slow growth thrive

The causes of slow growth and weight loss are many. This makes one-on-one consultations essential to diagnosing the problem and providing customized support.

In one extreme case, a baby was admitted to the hospital for feeding issues and weight loss. After discharge, I made a home visit and asked the mom to show me how she feeds the baby. She only had one bottle and a nipple caked with dried powder. This baby was sent to the hospital for feeding issues, but nobody assessed the mom to see what she was actually doing at home to feed the baby.

In another case, I met with a mom whose baby was discharged without adequate supplies for her baby’s feeding tube. She adjusted the baby’s formula and was adding her own mixes. She needed more adhesive to keep the NG-tube inserted, so she used adult Tegaderm. Still, the tube wasn’t staying in place. While they had already visited the pediatrician, the mom hadn’t communicated her challenges because she didn’t know any differently.

It’s these kinds of early struggles that can make developing pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) more likely, even for those children who outgrow their initial challenges. Getting these families access to early support can make all the difference.

How parents can improve feedings at home in cases of slow growth, weight loss or feeding tubes

Ask for a feeding plan

Key to helping parents deal with feeding challenges is providing better instructions when children are discharged from the hospital. NICU nurses are great about showing parents how to insert the NG tube, check placement and when to call for help.

Be sure to also ask when to increase the calories, when to visit a GI and when your child no longer needs the tube.

Get emotional support

With all the focus on feeding a baby with slow growth, lack of growth or weight loss, it’s hard to focus on self care. But it’s essential.

Moms need rest and breaks, especially those who are postpartum and are double feeding – pumping and giving bottles. Rally your support among family and friends. Don’t expect to be able to handle everything alone.

Set up a treatment space in your home

If your baby has a feeding tube, it’s important to designate a treatment space. Make sure this isn’t a crib, couch or play area. This helps your baby know what to expect, rather than fear having the tube inserted at any point in the day.

Hold your baby during feedings

Whether you’re bottle feeding or tube feeding, it’s important that you hold your baby during feedings. This helps with bonding and makes your child feel more comfortable eating.

Get in touch with Feeding Matters

If you’re struggling with feeding challenges, you don’t have to walk this road alone. At Feeding Matters, we have many resources for parents to answer questions and provide social and emotional support. One of our most helpful support programs is peer to peer mentoring, Power of Two.

Ensuring parents get support for slow growth, lack of growth and weight loss is crucial to mitigating the risks of developing pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). Not all parents will have access to a pediatric developmental nurse, home health or coordinated support between their pediatrician and a GI. It’s essential that parents get the information they need from the start, before being released from the NICU.

Babies and their parents depend on it.

Mary Anthony has been a pediatric nurse for nearly 40 years and is head of the High Risk Perinatal Program for Maricopa County in Arizona.