Category: Infant Growth

Building a care team for PFD

Published by Erin Ross, PhD, CCC-SLP, CLC on Feb 26, 2024

In Washington state, every child supported by early intervention (EI) for pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) is treated by a team that includes a nurse, dietitian and a speech and language pathologist (SLP) or an occupational therapist (OT). The clinicians work together to coordinate care and discuss each child’s needs. It’s a model of care that works –– but is also extremely rare.

Many states are moving in the opposite direction for EI –– providing children ages 0-3 with services from a single provider. This may be a physical therapist (PT), OT or an SLP. That clinician is expected to cover every area of the child’s developmental therapy. Even with the best intentions, clinicians will fall short of providing the comprehensive care required for PFD.

Outside of feeding clinics and children’s hospitals, many children with PFD are treated by a patchwork of clinicians who don’t easily coordinate care. Those who seek a spot in a feeding clinic face long waiting lists and typically experience severe symptoms of PFD.

Finding support for four domains of PFD

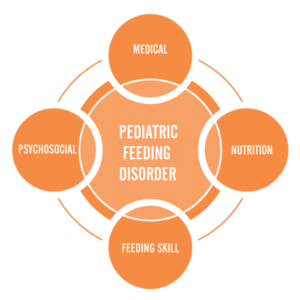

Pediatric feeding disorder affects four domains of feeding:

- Feeding skill: Actual feeding skills, such as chewing and swallowing and managing the sensory aspects of eating

- Medical: The body’s physical ability to digest food

- Psychosocial: Learned ability to eat without distress

- Nutrition: Willingness to eat a variety of foods with high nutritional value

Feeding Matters’ Coordinated Care Model examines the complexities of PFD through these four key domains that significantly impact a child’s lifelong well-being. Because PFD is so multidimensional, children need support to cover each domain. This requires a multi-disciplinary care team.

PFD can be well-regulated and treated through collaborative care and the proper support system. But for many parents, the job of cobbling together a PFD care team falls upon them.

Designing the all-star PFD care team

Symptoms of PFD vary for every child. Some common ones include a lack of interest or refusal at mealtimes, extreme picky eating and slow weight gain. If this sounds familiar, know that it’s not okay if mealtimes are a constant struggle. Unfortunately, some providers may discount these behaviors. A good rule when working with any clinician is that if you are worried, this means there’s a problem.

If you are building a care team for your child with pediatric feeding disorder, seek support from clinicians who can cover the four domains of feeding. Consider finding support from pediatric clinicians who work on telehealth if you live in an area with limited options.

Medical domain

This provider has expertise in your child’s overall medical health, such as a pediatrician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant. Their job is to identify when feeding needs additional assessment. If your child shows signs of PFD, you’ll need a provider who understands the disorder and the four domains that make up the coordinated care model.

Feeding skill domain

An OT or SLP with expertise in teaching the skill of feeding is an important member of your PFD care team. They’ll focus on the development and coordination of the sensory and movement skills that eating requires.

There’s overlap in the feeding skills and OT and an SLP can support, so be sure to describe your child’s challenges with the clinician. Ideally, you can work with both as they each bring expertise. Look for an OT and/or SLP with expertise in sensory and oral motor skills.

Psychosocial domain

Mental health providers, such as a psychologist or a licensed social worker, can help assess and treat the learned avoidance behaviors typically seen with a pediatric feeding disorder. For the child, this means managing mealtime behaviors and learned responses. This also includes modifying caregivers’ responses to the child’s behavior to promote a positive and successful feeding interaction.

Nutrition domain

It’s important to distinguish a registered dietitian (RD) from a nutritionist. In most states, individuals call themselves a nutritionist with no formal education or medical licensure association. Look for an RD with pediatric experience. Many RDs work over telehealth.

Finally and most importantly, you, as the parent, are a key member of the multidisciplinary team. You know your child best. It’s important you feel the team is listening to you and not just talking at you.

Tips for coordinating your child’s care

Ideally, your child’s care team will communicate on their own. When this doesn’t happen, serving as a middleman for provider communication is challenging. Ask your child’s clinicians to follow up with one another rather than passing messages and forms through you.

Tell the practitioner that you would really appreciate it if they would contact the other clinician. When your child is able to go to a multi-disciplinary team under one roof, that’s how they would function. Even when that’s not the case, you can still set that as the expectation for your child’s care team.

Most importantly, trust your gut. Many people are raised to think physicians are going to direct care. This is often true, but if you feel a provider is missing something or you want a second opinion, you are your child’s advocate.

If you think feeding is a problem, it’s a problem.

To find a licensed professional in your area, visit the Feeding Matters Provider Directory.

Dr. Erin Ross is a practicing SLP and the owner of Feeding Fundamentals, an organization that provides evidence-based professional training to advance the practice of infant feeding. She is a long-time member of the Feeding Matters Founding Medical Professional Council.

Getting the most out of feeding therapy for PFD: A step-by-step guide to finding the right pediatric feeding therapist

Published by Nicole Williams, OTD-OTR-L, at Desert Valley Pediatric Therapy in Arizona on Feb 15, 2024

When your child needs feeding therapy for pediatric feeding disorder (PFD), navigating the system to access treatment can be challenging. If your pediatrician recommends feeding therapy, the following are some tips for how to find the right match.

Understand the role of feeding therapistsFeeding therapy requires additional training that neither pediatric speech and language pathologists (SLP) nor occupational therapists (OT) typically learn in graduate school. Look for a clinician who has obtained this additional training and has been mentored by another experienced feeding therapist.

Both SLPs and OTs can be qualified to provide feeding therapy. There are times when one discipline is better equipped to support your child than the other.

SLPs have extensive knowledge of swallowing, chewing and the oral motor part of feeding therapy. If your main concern for your child is choking or chewing, speech therapists are best equipped to help.

An OT is an expert in sensory issues and texture aversions. If the feeling of food in your child’s mouth, combining foods or picky eating are the issues, look for support from an OT.

Even in the initial feeding therapy evaluation, you might want to request one specialty over the other. If you’re unsure, let the intake team know your feeding concerns. They should be able to match you with the right therapist.

Check your insurance benefitsIn many cases when a child needs feeding therapy, the referring physician will not indicate whether the therapist should be an SLP or an OT. In some cases, though, your insurance will specify coverage for one or the other. It’s a good idea to understand your benefits before requesting a therapy intake evaluation.

Set expectations from the startTo get the most out of feeding therapy, share your goals from the start. Even during the initial evaluation, it’s important that you and your child’s therapist have aligned goals. For example, if your child responds to a specific approach or personality, be sure to share that. In many cases, therapists can adjust to match your child’s needs. Part of the therapeutic use of self is learning to gauge and meet children where they are.

Feeding therapists have to be flexible. This means goals should be fluid from the start. If your child isn’t reaching their therapy goals, it’s time to adjust them. If your child has a setback, like a hospitalization, you may need to change your goals entirely.

Find out how to be a partner at homeAs feeding therapists, we only have one hour a week to work with a child. That’s why we typically ask parents to join us during sessions so you can continue the therapy at home. As much as parents need breaks built into the schedule, therapy is not the ideal time.

Expect collaboration

Expect collaboration

From the start, feeding therapy is collaborative. During the initial evaluation, you’ll set goals and therapy expectations together with the therapist. You should also expect your therapist to work closely with any other clinicians who support your child.

Know that feeding therapy is not linearUnlike the progress you might see in speech therapy, for example, feeding therapy tends to progress at a slower pace. Overall, you’ll want to see an upward trajectory of progress in feeding therapy, but it’s normal for your child to have ups and downs. What you don’t want to see is a plateau over time.

Don’t be surprised if it takes time to see progress in feeding therapy. Some kids are slow to build rapport and feel comfortable with a therapist. If your therapist is answering your questions, being collaborative and is confident in their approach, be patient.

Don’t be afraid to pivot if it’s not working outIf you’re not seeing positive progress over time or if your child’s feeding therapist isn’t a good fit, be sure to raise these concerns. In many cases, the feeding therapist can make improvements.

If results don’t improve, your child may need support from another therapist. Try switching therapists to see how your child responds. If that doesn’t help, your child may need support from another discipline entirely –– such as a gastroenterologist or a psychologist.

Consider the following questions and answers for a potential feeding therapist:

Q: How long have you been seeing and treating children with pediatric feeding disorder? A: Look for someone with at least a few years of experience.

Q: Are you familiar with the Pediatric Feeding Disorder Consensus Definition and Conceptual Framework article published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition? A: If not, look for someone willing to read the article.

Q: Do you have specific education and training regarding pediatric feeding disorder? A: Look for someone who has additional training to understand the issues.

When therapists finish school, they usually don’t just jump into feeding therapy. Feeding is a specialty within speech therapy and occupational therapy that requires additional training and guidance under an experienced feeding therapist.

Q: Have you seen a child who’s had a similar experience?A: Finding a therapist familiar with your child’s specific feeding challenges is important. Don’t be afraid to ask this specifically to be sure you’re comfortable with the answer.

Q: Describe your overall approach to pediatric feeding disorder.A: Look for someone who understands the medical, nutrition, feeding skill and psychosocial domains and is willing to collaborate with a multidisciplinary team.

Q: How do you determine if a child is growing well? A: Look for someone who follows your child’s growth pattern, not just a standard growth chart.Q: How do you share the results of diagnostic testing, treatment goals, and other information with me and other providers treating my child? A: Look for a practitioner who partners with professionals in other disciplines and keeps open lines of communication with them as well as with you. Make sure they are willing to provide you with copies of reports and take the time to go over reports with you.

A story of triumph over pediatric feeding disorder

Published by Feeding Matters on

The way pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) manifests in each child is as varied as the children themselves. But so many stories of parenting children with PFD are the same.

An infant struggles to feed and gain weight. Parents work tirelessly to feed their children and juggle medical visits. They search in the dark for a diagnosis of a complex problem they don’t understand, all while feeling alone and at fault.

Raising a child with PFD is a journey that rarely has a final destination. With the right support and care, it does get easier. This is the story of one mom of a son with PFD and how she’s gone from seeking help to supporting others.

One family’s journey with PFD

From the start, Erin Avilez’s son, Julian, struggled to breastfeed and gain weight. Her doctors were concerned about her baby’s measurements throughout her pregnancy. When her amniotic sac fluid was low, Avilez was induced at 37 weeks.

Julian was born at 5 pounds and right away had trouble sucking and taking in enough food at each feeding. Avilez switched to bottles, but Julian continued to undereat. “Within the first few months, there were already red flags that he was underweight and not getting enough nutrition,” she says.

Avilez and her husband started by switching formulas to see if Julian had some sensitivity to some ingredients. Still, they didn’t see much weight increase. Things got worse when her pediatrician sent Julian to a pediatric gastroenterologist. “That’s kind of where the horror of the story started,” she says.

Julian’s pediatrician and the GI weren’t communicating or working together and sometimes had different goals. “The GI’s only goal was for Julian to gain weight and cared less about how it affected his feeding,” says Avilez.

Julian got a nasogastric tube (NG tube) at three months old. The increase in calories made him vomit a lot, and he regularly pulled the tube out. Any time he pulled the tube out, Avilez would have to call her husband to come home from work so the two of them could force the tube back in. Insurance only covered a few tubes, making this devastating ritual even more difficult. Julian developed an oral aversion that he never had before and wouldn’t even let his parents touch his face. By seven months, Avilez insisted the NG tube be removed.

When Julian’s GI recommended a gastrostomy feeding tube (G-tube) instead, Avilez knew they needed a second opinion. Julian took some formula and solid foods orally, and Avilez thought they could build on that. A new GI at Phoenix Children’s Hospital agreed.

With a new pediatrician and GI, Julian’s doctors started working on finding a diagnosis. He was also able to join their intensive feeding therapy program. “The new GI doctor we saw listened, and he offered empathy and support,” says Avilez.

When Julian was 3.5, his family finally got a diagnosis of what caused his pediatric feeding disorder. A liquid and a food study showed that he has gastroparesis, a condition where the stomach muscles do not work properly to empty waste.

Now that Julian has a diagnosis, he’s able to take medication to help his gastric delayed emptying, as well as an appetite stimulant. He also drinks Ensure Clear to add more calories to his diet. Julian has an aversion to any formula or dairy because of his early experience with the NG tube.

In the past six months, Julian was finally registered low on the weight chart for the first time. “This is huge for him,” says Avilez.

Still, says Avilez, their struggle is never far from her mind. She dreads visits to the pediatrician when she knows Julian will be weighed. “Even today, a week before his appointments, I start getting stressed out because I know we have to get on the scale,” she says.

Finding support from other families with PFD

Julian was born during the pandemic, and Avilez left her job as a social worker to take care of him and to get to all his appointments. She suffered from postpartum depression and felt overwhelmed, alone and isolated.

“I knew there has to be some type of service out there to help moms like me,” she says.

Avilez searched online and found Feeding Matters. She requested a peer-to-peer mentor and was matched with another mom who shared her experience. That empathy was powerful. “She listened to me. The first time I got off the phone with her, I started crying that somebody understood what I was going through,” says Avilez.

Avilez’s mentor also told her she was doing a great job. “Throughout this process, nobody told me I was doing a good job, not the doctors or anyone on his care team,” she says.

Avilez’s introduction to Feeding Matters was the first time she learned about PFD. “I felt so validated that we weren’t the only ones concerned about not knowing what was going on with our son and not hearing about it from our doctor,” she says.

Today, Avilez is a peer mentor to other parents raising a child with PFD. She’s grateful to have support and to be able to pay it forward. Her hope is that more clinicians and hospitals will inform parents about PFD from the start. “I wish that when you have a child with feeding difficulties, someone from the start would offer resources,” she says.

Key takeaways for supporting your child with PFD

Avilez offers the following advice to parents raising a child with PFD.

- Find a supportive care team: If the doctor’s not listening, find a more supportive provider. Having a good team in place makes all the difference.

- Trust your instincts: It’s okay to get a second opinion and ask questions. Keep advocating for your child because you know your child best.

- Find friends, family or a peer mentor: Find someone who will listen and understand so that you feel less alone.

Behind the headlines: Exploring the complex world of tongue tie releases and pediatric feeding disorder

Published by Feeding Matters on Jan 29, 2024

A tongue tie release procedure (frenectomy or frenotomy) is increasingly prevalent among children with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) that the majority of them have had it, or their parents at least considered it.

That’s because difficulty breastfeeding is common among children with PFD. A frenectomy is often considered an early treatment to improve latching while breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding is a complicated process that doesn’t come naturally to all mothers and babies. It takes multiple muscles, the ability to coordinate sucking and breathing and the strength to stay awake through strenuous exercise. Releasing a tongue tie can seem like an easy fix.

But for kids with PFD, a frenectomy doesn’t necessarily fix feeding problems and is instead one step along a journey of treatment when the frenulum is not the sole cause for feeding dysfunction. For some babies, a frenectomy can be helpful. For others, it’s not necessary. And in some rare cases, the elective procedure causes harm. While generally safe and often performed by dentists, the procedure maintains the potential to do harm, without a significant assurance of benefit. The procedure is sometimes not covered by insurance and can cost hundreds of dollars.

The debate about releasing tongue ties recently was brought to the forefront in The New York Times article, Inside the Booming Business of Cutting Babies’ Tongues. Showcasing many cases where the procedure was unnecessary or went wrong, the article paints a picture of a procedure as controversial as it is common.

Tongue tie releases for children with pediatric feeding disorder

What’s clear from working with countless families of children with PFD is the benefits of a frenectomy vary on a case-by-case basis. Most importantly, it should never be a result of a self-referral to a clinician who advertises the procedure as the obvious answer for breastfeeding difficulties. Instead, the decision should be shared by the family and a qualified clinician.

Nikhila Raol, MD, MPH, pediatric ENT and an associate professor at Emory University School of Medicine who researches ankyloglossia, or tongue ties, says getting the procedure is a multifactorial decision, meaning it

takes careful consideration with advice from multiple clinicians working together. “Even when the tongue tie is physically obvious, I’m still a proponent of having a functional evaluation with a feeding therapist or lactation consultant with real expertise in evaluating feeding and latch before a procedure. What I’m finding in my ongoing research is that even if a baby has a tongue tie, if the mother’s breast shape is favorable, it may not cause as much issue as we think,” she says.

Breastfeeding often takes some time for babies and moms to adjust. Dr. Raol recommends most parents wait at least two weeks to a month of trying ways to adjust to breastfeeding before getting a frenectomy on a newborn, assuming that the weight gain is acceptable. “Sometimes, you just have to give the baby time to figure it out and the mom’s body to adjust to breastfeeding. Figuring out how to latch and how to get a strong suck sometimes just get better with time,” she says.

Jaclyn Pederson, CEO of Feeding Matters, sees many parents consider the benefits of a frenectomy when breastfeeding or picky eating is challenging. As a parent, she did the same and released the tongue tie on one of her sons. She says that while a tethered tongue is a concern, what can get lost is the nuance that it’s one concern of many –– especially when a child is diagnosed with PFD. “What we know about PFD is that it’s incredibly complex. One of the first things that we share with families is helping them understand that there’s not just going to be a switch that’s flipped to make their feeding journey easier. It’s a series of small milestones that build over time,” she says.

The challenge of considering a frenectomy as a quick fix to difficulty breastfeeding is not just disappointment when it doesn’t work. It can mean overlooking the actual root of the problem, such as some other problem with feeding or swallowing. “Assuming that the surgery is the solution, even as minimal of a procedure as it is, still leaves out a lot of other feeding components,” says Pederson.

One family’s tongue tie release story

When Emily Garlinsky’s son, Landon, had trouble breastfeeding, she was at first confident a tongue tie wasn’t the issue. Clinicians in the hospital when he was born, as well as her pediatrician, assured her his tongue looked normal.

But as Landon continued to struggle and Emily shared her feeding frustration in Facebook groups, she kept hearing people recommend a tongue tie evaluation. By the time Landon was four months old and still struggling to feed, Emily thought it was time to revisit the issue. Landon was already in feeding therapy at that point, and his therapist agreed the procedure might help.

Emily went to a pediatric dentist who told her Landon had a lip tie and a tongue tie. Landon underwent the procedure, but his feeding didn’t improve. He did well with the surgery, though, and Emily is glad they did the release. “There’s a lot of back and forth on Facebook groups from people who regret it. It didn’t help with feeding for us, but other aspects of the release are helpful for speech,” says Emily.

True or false? Tongue tie myths

Dr. Raol warns against peddling fear to encourage parents to act for their babies or overpromising treatment results. “You must be careful because breastfeeding mothers are a vulnerable population. A new mother just wants to do her best,” she says.

Following are some common assumptions around tongue tie release procedures. Some have no research evidence to support them, and others have emerging research.

Tongue ties cause swallowing difficulties: Maybe

Dr. Raol is rigorously studying this in her research. She says, “When you swallow, your tongue starts the pharyngeal squeezing process. When a child can’t squeeze hard, we think this could cause food or liquid to spill into the airway as it is trying to enter the esophagus.”

Tongue ties cause reflux: Unknown

Reflux is normal in babies due to low tone of the sphincter muscle that separates the stomach from the esophagus. Dr. Raol explains that it has never been objectively demonstrated that a tongue tie is responsible for this through aerophagia, or swallowing air, which is the proposed mechanism. However, some studies have shown that reflux symptoms improve after frenectomy. What we do not know is if the symptoms would have just gotten better with time.

Tongue ties cause problems with craniofacial development: Maybe

There’s not a lot of existing research evidence to support this. More research is needed.

A laser is better than clipping for a tongue tie release: Maybe

Many parents hear on social media advice to go to a pediatric dentist instead of an ENT for a tongue tie release because dentists use a laser.

More research is needed, but a review of the existing research found the laser procedure resulted in a shorter surgery, without suturing, and less postoperative pain.

Tongue ties cause speech issues: Maybe for some

The jury is still out on this because Dr. Raol explains there is a deficiency in the literature. Most of the research comes from English-speaking countries, but there’s a difference in how the tongue works in other languages. “In Indian languages, we use the tongue a lot more with certain sounds where you put your tongue far back on the palate. In India, the primary reason kids get a frenectomy is for speech.”

For serious speech issues, though, says Dr. Raol, a tongue tie release is not a quick fix. “In the case of expressive aphasia or something like that, we should not be telling families that clipping a tongue tie will solve that problem,” she says.

You should go to a pediatric dentist for a frenectomy: Only with a diagnosis or consultation from an ENT, lactation consultant, feeding skill specialist, or pediatrician first –– and in that case, the ENT or a pediatric dentist could do the procedure

Breastfeeding is complicated, and any issues should be evaluated by an expert who considers both the baby’s and the mother’s anatomy. Misdiagnosing a tongue tie as the issue can mask other underlying problems, such as PFD.

While it’s true that a frenectomy is a minor surgery and a trained clinician can safely manage the procedure, it still requires careful consideration.

Be wary of a clinician who promises the procedure as a quick fix in exchange for out-of-pocket payment.

Signs your child might need an evaluation from a feeding therapist or lactation consultant

While some children’s tongue ties are apparent even to the untrained eye, it’s still important to get a thorough evaluation before scheduling a frenectomy. Under no scenario should you self-refer or decide based on advice from a friend or a clinician on social media. While this may seem obvious, many people are doing just that and then paying cash for the elective procedure. “We’ve seen this become the number one thing families are thinking about when they have trouble breastfeeding because they hear their friends talk about it and see it online,” says Pederson.

Following are some signs your child might be a good candidate for a frenectomy:

- Your child is not steadily gaining weight from breastfeeding.

- There is some tongue tethering.

- Pain while breastfeeding goes beyond the initial adjustment period.

- You’ve tried various positions and breastfeeding techniques.

- The number of times your child feeds per day remains the same over time. Your baby should become more efficient at feeding as she grows.

When seeking the right clinician, Pederson recommends starting with your pediatrician and an ENT, who will conduct a thorough evaluation. “Look for a professional who shares the pros and cons of a scenario versus one who pushes a treatment as the answer to everything. Explaining the nuance is how you know that a professional really understands how complicated tongue ties are and the issue of feeding is in general,” she says.

Like any treatment or therapy for children with PFD, managing feeding requires a degree of personalized medicine. “Some kids really do need a frenectomy. But if all I have is a hammer, everything is a nail. The tongue is just one piece of the puzzle,” says Dr. Raol.

In the end, getting even a minor tongue tie release surgery is a decision parents should make based on clinical advice, says Dr. Raol. “If you’ve tried everything, and there does seem to be some tethering, and you’re fully aware that this may or may not help, then I don’t think the procedure is unreasonable.”

Feeding Matters blog posts are written by the communications team at Feeding Matters and designed to continue the conversation and awareness around pediatric feeding disorder based on expert opinion interviews.

Feeding questionnaire a springboard for physical therapy needs

Published by Karen Crilly, PT DPT, Advanced clinical specialist at Texas Children’s Hospital on Oct 20, 2023

How one physical therapist uses the Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire to identify a child’s areas of need and how she can help

Feeding challenges never occur in a vacuum. While I’m neither a speech therapist or a feeding therapist, the Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire® (ICFQ©) from Feeding Matters remains one of my most important assessment tools in my initial encounters with new patients.

The ICFQ was authored in partnership with internationally renowned thought leaders representing multiple disciplines related to feeding. It’s an age-specific tool designed to identify potential feeding concerns and facilitate discussion with all members of the child’s healthcare team – including physical therapists (PT).

Based on the caregivers’ responses to six questions, the ICFQ has been shown to accurately identify and differentiate pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) from picky eating in children 0-4.

Using the feeding questionnaire as a physical therapist

Whenever I meet with a new PT pediatric patient at Texas Children’s Hospital, I spend the first session speaking to the family to determine how we can help the whole child.

For example, I recently was working with a family in the plagiocephaly – head-shaping – clinic at Texas Children’s. When I asked the parent about feeding, she responded that the baby just won’t stay still to eat. That response led me to ask more questions about feeding. I learned the baby has torticollis – tightness of neck muscle that causes the baby to turn to one side. Plus, the baby was dysregulated, which could mean a neurological issue. I asked about reflux, which could be a gastrointestinal issue. I knew how to help in some areas as a PT, and I knew to refer the family to an occupational therapist and a speech pathologist.

I can’t even describe how relieved this parent was. When it came to feeding, everyone else had simply told her to “keep trying.”

While physical therapy focuses on a child’s functional mobility, no movement’s isolated from the rest of a child’s health. Movement takes mental and physical regulation. An infant requires proper nutrition to perform at their highest level. A child without enough calories doesn’t have the necessary energy to make the most progress in physical therapy – or any other therapy, for that matter.

6 feeding questions that help me identify physical therapy patients’ needs

There are six basic questions on the ICFQ that clinicians identify when a child has a feeding issue. As a physical therapist, responses to the questions highlight issues around endurance, function level and the parent’s understanding of the child’s needs.

Following are the six questions and how the responses help me as a physical therapist.

- Does your child let you know when he/she is hungry?

This question gives me insight into how well parents understand their child’s communication cues. Recognizing an infant’s or nonverbal child’s cues allows parents to know when a child is hungry, uncomfortable or tired. This communication is essential to the parent’s ability to do PT exercises at home.

- Do you think your baby/child eats enough?

Often, the responses to this question are cultural. Among the patients I see at Texas Children’s, I find some cultures expect babies and children to eat more than others. This is an opportunity to educate parents about what is typical. For those babies and children not getting enough nutrition, it’s a chance to refer them to specialists who can help.

- Do you have to do anything special to help your baby/child eat?

This question helps me gauge a baby’s stamina level. The baby may be having trouble coordinating breathing with swallowing. This tells me that in physical therapy, I need to work on the baby’s ability to open her chest out wide and back in. The goal is to increase the baby’s endurance to work for 30 minutes of exercise. That causes fatigue at the time, but it actually builds stamina for later.

A baby who doesn’t have the endurance to finish feeding isn’t likely to have the energy to make as much progress in physical therapy. This makes getting more calories into the baby especially relevant for PT.

- Do you have to do anything special to help your baby/child eat?

This question helps me determine when a baby is dysregulated. It means I need to refer to a specialist who can help the family uncover why feeding isn’t typical.

In physical therapy, I’ll determine whether the child needs to work on muscle retraction. This is one of the issues I see often in infants, especially, and sometimes even older children who are having trouble feeding. Retraction takes them away from their midline without being able to find their center again easily. This makes it difficult to eat.

As a physical therapist, I’ll work with the baby on midline rotation. We work on coordinating the movement of opening and closing the arms and chest. The baby’s shoulders should expand back and then be able to come back to center. The baby should be able to find his flexion and make symmetrical motions in the upper and lower body.

Working on the body in this way can improve feeding, supporting the therapy that speech pathologists and occupational therapists are doing as well.

- Does your baby/child let you know when he is full?

When a baby is not recognizing fullness, this indicates there might be a chronic condition. Once full, a baby should cry, turn the head, push away the breast or bottle or spit out milk. But if a baby just keeps eating, this is a cue that the family needs a referral to a specialist.

As a physical therapist, it helps me identify a baby’s level of function.

- Based on the questions above, do you have concerns about your baby/child’s feeding?

Responses to this final question provide an opportunity for education. I’ll know how much information I should give parents on typical development for their child’s age and stage.

It’s also an opportunity to encourage parents who need a referral to go ahead and make that appointment.

As physical therapists, we’re not just looking at the legs and the feet. Treating our patients means treating the whole patient.

Knowing how a child is feeding doesn’t only alert me to a patient’s nutrition needs. It helps me identify other issues a child might be experiencing. Each question in the ICFQ paints a picture of the whole child’s needs.

Karen Crilly, PT, DPT, MAPT, CBIS, is an advanced clinical specialist at Texas Children’s Hospital who has dedicated her professional life to forming a strong background and expertise in the assessment and treatment of infants and children with chronic and complex developmental and/or neuro-motor impairment.

Supporting a smoother transition to home for NICU babies

Published by Feeding Matters on Oct 02, 2023

In his years as a neonatologist, Vincent C. Smith, MD, MPH, has found anecdotally and in his research that the clinician managing a family’s discharge from neonatal intensive care units (NICU) disproportionately impacts patient outcomes.

Smith, the division chief of newborn medicine at Boston Medical Center, led a study examining how families are prepared for discharge and found significant variability in outcomes. Families with a primary nurse invested in their transition home after NICU discharge fared better. “It wasn’t about gestational age, length of stay or medical complexity. That discharge clinician sets the course,” he says.

Smith wasn’t alone in his findings.

Clinicians across disciplines working with NICU families, as well as parents, find that whether families are ready for the dramatic adjustment of going from a team of clinical support to being on their own is usually left to chance.

Erika Goyer, parent liaison and communications director of National Perinatal Association (NPA), says, “Medical care is siloed. You have a high-risk pregnancy with one team. Once your baby is born and needs intensive care, they’re transferred to the NICU, and you move on to another team. As your baby progresses, you’re supposed to move on to a team at home. What that team comes down to at home is usually just you.”

An estimated 9-13% of newborns in the U.S. require neonatal intensive care for complex medical needs, a number that’s increasing.

To support these families, a cohort of multidisciplinary clinical leaders – including Feeding Matters – and parents came together to standardize NICU discharge. Their hope with the NICU guidelines is to improve families’ experience, reduce stress and help NICU babies access the follow-up care they need to thrive.

Why NICU families need more support

If you speak to NICU families after their first night home, says Smith, what’s true for all of them is that none slept comfortably. Even in the best circumstances, there tends to be a lack of continuity for families. “A lot of families feel abandoned by the NICU. They get their papers and their baby, and they’re joyous. Then they go from bells, whistles and lights, with 50 people around to just them and a baby. And they just had to make do.”

Kristy Love, executive director of NPA and NICU patient advocate, knows firsthand what it’s like to have a child in the NICU. Both of her children were NICU babies. She spent as long as three months in the hospital with one of her kids. What she’s found in her years supporting other parents is that not much has changed since she struggled to transition home with her preemie over 20 years ago. Parents still contact her as much as a year after leaving the NICU to share their struggles. “We have all this support in the NICU during our journey, and then once we go home we’re flying solo,” she says.

She shared her concerns with Smith at a board meeting for the National Perinatal Association, and from there, the NICU discharge guidelines were born.

NICU discharge guidelines explained

The National Perinatal Association spent a year looking at NICU discharge factors like research, protocols, insurance benefits and parents’ experience. The National Perinatal Association looked at NICU discharge factors like research, protocols, insurance benefits and parents’ experience. They worked together with a group of multidisciplinary experts, including Cuyler Romeo MOT, OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC, director of strategic initiatives at Feeding Matters. Together the content experts finalized the NICU guidelines and submitted them to the Journal of Parentology for peer review.

The guidelines address topics like:

- Basic information

- Anticipatory guidance

- Family and home needs assessment

- Transfer and coordination of care

- Other important considerations

Smith says there are around 300 guidelines, and no one expects NICUs to adopt all of them at the same time. The hope is that hospital neonatal teams will identify a few of the guidelines particular to their organization and population and then build from there. Over time, they can gradually implement all of the guidelines.

“Many people get overwhelmed when they see the challenges before them because they don’t necessarily have the team, resources or funding. I find everybody can make small changes leading to bigger changes,” says Smith.

Having peer-reviewed guidelines is an important step to improve all families’ experiences. Organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics and others recommend that hospitals have a transition plan, but it was never formalized until now. “Everybody said you needed to have a plan in place to execute, but they weren’t given any guidance on it,” says Goyer.

Pilot program to put NICU guidelines into practice

Having NICU discharge guidelines is an important first step. Putting it into practice in the field is essential. When the team who wrote the guidelines looked for a NICU as a pilot program for implementing them, they chose Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Romeo, who served on the guidelines committee, is a clinician there. Plus, a local community partner, Smooth Way Home, helps families transition home from the NICU.

In January 2022, Romeo says they launched the pilot program by identifying barriers to a smooth transition home. Through crowdsourcing in the unit and close collaboration with the developmental RNs, Nancy Gates and Ashley Lee, they chose three areas of focus:

- Processes: Discharge processes and coordination

- Providers: Community provider readiness to accept infants into community-based care

- Parents: Parent and caregiver education and advocacy to support optimal care and development at home

The team found that families may not receive developmental care support once they were discharged home. It was unclear if families referred to the Arizona Early Intervention Program (AzIEP) were receiving care. Not all children discharged from the NICU qualify for early intervention services despite their difficult beginnings. If they did qualify, getting that first appointment proved challenging. “Before piloting the guidelines, our NICU team would refer families to AzIEP and then have no way to know if they received care,” says Romeo.

A long standing barrier to accessing services after discharge was knowledge sharing. Nancy and Ashley reported that early intervention agencies often were unable to access the infants’ medical records. Without this information it was difficult for families to qualify for service.

To address these issues, says Romeo, the developmental RNs are leading the way in investigating process improvements for information transition while working closely with Smooth Way Home as a liaison for a warm handoff into the EI system.

It’s a multi-year pilot program that we hope will grow into a larger program if we are able to secure funding. Our families deserve to be well prepared so they can finally enjoy their baby at home.

Romeo says the guidelines lead to better outcomes, but funding remains the most significant barrier. “This work is done while the clinicians continue to fulfill their typical job demands. Nancy and Ashley do not have time allocated for this project, but they feel it is vital to the infant’s health and development so the work continues.”

Everyone involved says improving the continuum of care for NICU babies and their families requires tremendous work. But every level of improvement matters to the families who benefit from it. As Goyer says, “This is all about making sure families aren’t alone and have the support and skills they need from the clinicians and community around them.”

Everyone involved says improving the continuum of care for NICU babies and their families requires tremendous work. But every level of improvement matters to the families who benefit from it. As Goyer says, “This is all about making sure families aren’t alone and have the support and skills they need from the clinicians and community around them.”

Visit NICU to Home for more information about the NICU guidelines. Feeding Matters has been a strategic partner in creating and implementing the guidelines, together with NPA. For more information about how we help families of children with pediatric feeding disorder, click here.

Overturning insurance denials for PFD

Published by Feeding Matters on Sep 20, 2023

Navigating insurance coverage for pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) exacerbates the challenges of dealing with a complex medical diagnosis. The ICD-10 code that made PFD an official diagnosis meant getting the green light from insurance is significantly more straightforward today. But many families still face insurance denials.

Anyone who’s ever spent time on hold with an insurance call center or repeated a medical story multiple times to different agents knows how frustrating these calls are. Managing insurance bureaucracy while parenting a child with PFD is exhausting.

Stages of overwhelm are typical for families of children with PFD. Parents of young children in general are often sleep-deprived and stretched thin while balancing parenthood, work and life. Add multiple clinical appointments and round-the-clock feeding sessions to the mix, and it’s no wonder PFD parents are stressed.

How one mom overturned an insurance appeal to for an important treatment

Emily Adams, mother of 6-year-old Morgan and a long-time insurance insider with USI, shares how she battled insurance denials and offers tips for other families.

Morgan had severe reflux as a baby and only ate from a bottle in her sleep. Despite “dream-feeding” all night, she continued to lose weight. At 1.5 she got an NG tube to get the nutrition she needed.

Eventually, Morgan’s reflux improved with the proper medication. Emily then searched for a feeding program that would repair her toddler’s relationship with food. Finding the perfect program at Nationwide Children’s in Columbus, Ohio and securing a spot there was a feat of its own. Getting insurance to pay for it proved just as challenging.

Morgan at that point didn’t have an official diagnosis because the ICD 10 code was not yet established. Clinicians had to get creative with billing codes for Morgan’s therapy sessions. It wasn’t unusual for United Healthcare to deny them. That meant Emily was used to appealing denials by figuring out what code to use and then having Morgan’s clinicians resubmit them.

This came to a head one Monday morning when Emily and Morgan prepared to temporarily move to Columbus to enroll in Nationwide Children’s outpatient feeding program. There was a two-year waitlist for the spot. It was then that the family learned their insurance wouldn’t preauthorize coverage.

Emily, who works in the insurance industry, managed to identify the insurance broker for her husband’s employer. Emily knew she recommended that the insurance agency deny their claim. She reached out and realized the broker assumed the cost would be exorbitant and the need wasn’t great. “Nobody has any idea what the expense is for each of these children because they all need different types of care at different stages,” she says.

Emily explained that the cost of not covering the program would be much higher if Morgan continued to need an NG tube and years of therapy. She convinced the broker to recommend the approval. “It was very last minute and very stressful. I’m in the industry and know how the game is played, so it was extra frustrating to see this happening to my kid,” she says.

6 tips for insurance appeals

Emily recommends the following tips for navigating insurance denials.

1. Be a fierce advocate for your family and child. When the insurance company denies coverage, insist that you’re not accepting no as an answer.

2. Speak to different people. Talk to your employer’s human resources department to find out how to reach the company broker. Explain to them about the treatment and the cost exposure. They may assume that the costs to treat your child are much more than they are. Present a budget of what your kid needs and what the expenses are.

3. Have a peer buddy who’s navigated this before.

4. Let a family member or friend go to important appointments with you. “In fight or flight mode, you’re not thinking clearly. You may not recognize the whole picture and miss a big piece of information,” says Emily.

5. Take detailed notes. “We hear things differently when we’re in stressful situations,” says Emily. A notebook to refer back to meant she could better advocate for her daughter.

6. Lean on your provider to help you advocate for coverage. Many hospitals have a patient advocate or liaison to help families navigate benefits and the appeal process.

When calling your insurance company, here’s a sample conversation Emily recommends using:

I know you don’t understand the complexities of my child’s condition. She needs speech and language pathology, occupational therapy, feeding therapy with a dietitian, pediatric psychologists and nurse practitioners to deal with this illness. Delaying care can delay my child’s progress and make it more expensive.

I need your help getting me to someone who can help all those codes appropriately process. Can you connect me to someone who has a better understanding of billing for complex conditions?

I’ll stay on the phone until you figure this out.

Navigating insurance for a child with PFD is frustrating, but it’s not impossible. Like so much of parenting, says Emily, “You have to be a fierce mama bear, talk to different people and make someone listen to you.”

Click here to download more information about your right to appeal an insurance denial and access a sample appeal letter template for PFD.

Breastfeeding for babies in the NICU and beyond

Published by Joy Browne, PhD, PCNS, IMH-E on Sep 13, 2023

Can I breastfeed if my baby is in the NICU?

The journey of nurturing your newborn is more complex when your baby requires specialized care. One common concern is whether you can breastfeed a baby in the NICU. The answer is a resounding yes. Breastfeeding has many benefits, especially for premature or medically fragile infants. NICUs will often actively encourage and support breastfeeding, recognizing its vital role in promoting bonding, immune system development and overall growth. While it might require extra patience and support from both you and the NICU staff, remember that you are an essential part of your baby’s care team. Your commitment to breastfeeding can provide comfort, nourishment and a sense of familiarity to your baby during this critical time.Benefits of breastfeeding in the NICU

A mother’s breastmilk is specially designed to meet their baby’s unique nutritional needs, whether they begin their lives in the NICU or typically develop and are born at term. Babies in the NICU, especially, benefit from breastmilk for their health and development. A study in Nature.com shows, “…early human milk feeding is associated with a decrease in mortality and morbidity in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), decreased rates of illness and rehospitalization in the first year of life and improved neurodevelopmental outcomes.” We also know that a mother’s colostrum is a powerful protector. Many nurseries will ask mothers to express colostrum to be used for oral care and first tastes while in the NICU. Besides breastmilk’s nutritional benefits, breastfeeding also may facilitate bonding between mother and baby, reduce a mother’s stress levels, and decrease the risk of postpartum depression.Is bottle feeding easier than breastfeeding?

It’s commonly misunderstood that breastfeeding is harder for babies than bottle feeding. Instead, studies show in many instances that breastfeeding is easier than bottles.- With bottle feeding, babies may work hard to extract milk from the nipple, expending extra effort to consume their required nourishment.

- With breastfeeding, babies can grasp, latch and regulate milk flow according to their comfort and pace. They control how much they consume and how to coordinate their sucking with breathing.

Why skin-to-skin contact matters for babies and new moms

One of the most important benefits of early breastfeeding is skin-to-skin contact. It’s an intimate and powerful connection a mother will have with a baby. Skin-to-skin contact creates physiologic organization of both the baby’s and the mother’s bodies. Following are some ways new babies and mothers benefit from skin-to-skin contact:- The mother’s body supports the baby’s temperature regulation. Once the fetus leaves its temperature-controlled environment of the uterus, the mother’s physiology heats up to ensure the baby is warm enough.

- The mother’s breathing helps to regulate the baby’s breathing.

- The mother secretes oxytocin, also called “the love hormone,” when the baby is nearby, supporting attachment as well as social and emotional development.

Continuing your breastfeeding journey beyond the NICU

Just because you know the benefits of breastfeeding doesn’t mean it’s easy. Having a baby in intensive care is extremely stressful – often coming after a stressful pregnancy, labor or delivery. The stress of these circumstances could interfere with successful breastfeeding, so mothers who can’t breastfeed should never feel guilty. Even with the best intentions, there are variables new mothers have to manage to be successful at breastfeeding. All mothers – especially those with babies in the NICU – need more support for breastfeeding from policies, NICU resources and community support. Following are some breastfeeding resources available:- Hospitals usually have lactation consultants on staff for in-patient support and outpatient appointments

- LaLeche League operates in most communities.

- The Affordable Care Act in 2011 made coverage of lactation consulting a federal requirement for mothers from the prenatal period through weaning. This includes the cost of breast pumps. If your health plan fails to provide coverage, the National Women’s Law Center has a script to use when calling a health plan.

- SimpliFed provides a virtual baby feeding and breastfeeding support service, fully covered by health plans in all 50 states.

Continuing breastfeeding at home after discharge from the NICU

Babies in the NICU typically eat well at discharge but may have eating difficulties around two to four months. This is a period where babies’ brains are reorganizing, which leads to a change in the way they eat. It’s essential that babies get the most positive feeding experiences at this stage. Researchers have found that by three months, babies’ brains are about 65 percent the size they’ll be in adulthood, making the period around and right after a time of huge brain growth and organization of neurons. Any unused neurons are shed. This is why early experiences impact brain organization, and lay the foundation for all behavior – including eating. Professionals who support families after NICU discharge need more information about attending to the eating needs of these babies and their development. Educational programs about the science behind supporting babies’ transitions into their homes are essential for early intervention providers. By understanding the benefits of breastfeeding in the NICU and beyond, parents can make informed choices that support their baby’s health journey. It’s up to everyone who supports families with new babies to make caring for them easier.Joy Browne, PhD teaches multi-disciplines in areas of development from newborn to very young infancy, especially for babies who start their lives in intensive care. Her research has helped to develop standards of evidence-based care for infant and family centered developmental care.

Focus on Food Safety

Published by Anna Busenburg, RD, CSP, LD, CLC on Sep 05, 2023

This blog post is published as part of a paid partnership between Feeding Matters and Reckitt Mead Johnson Nutrition. Learn more about our corporate partnership program and ethical standards for collaboration.

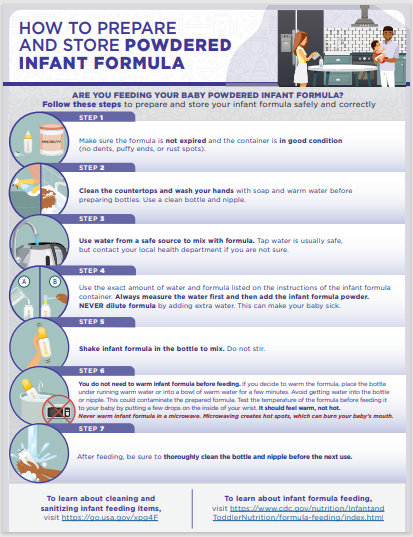

There are many opinions on using human milk or infant formula when it comes to feeding your baby. Most of the focus goes into what is being fed to your child, but less emphasis is placed on the safety of how feedings are prepared. Unless you are directly breastfeeding your child, you need to consider food safety when preparing infant bottles or tube feedings.

This focus on food safety has been front and center over the last couple of years since infant formula recalls have been in the news. These recalls occurred due to microorganism contamination concerns in a manufacturing facility. Food safety matters and is why liquid ready-to-feed or concentrated formulas undergo a heat treatment that sterilizes the product. Powder formulas are not sterilized, which poses an additional risk for contamination when incorrectly handled and prepared. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the regulatory and enforcement authority over the manufacturing and distributing of infant and pediatric formulas. It is important to consider food safety when preparing both infant formula (< 12 months old) and pediatric formulas (> 12 months old) being fed via a bottle or a feeding tube.

For families preparing pediatric feedings at home, it is important to remember these safety tips:

- properly wash your hands

- clean/sanitize feeding equipment and preparation space

- store prepared feedings appropriately

- follow the recipe from your provider

Practicing good hand washing techniques helps to diminish the risk of transmitting germs. Make sure that hands are washed for a full 20 seconds with soap and water. Proper handwashing is the #1 method of preventing the spread of germs for your child.

When bottles or pump parts are being used, cleaning them regularly is essential. It is also recommended to sterilize these components in the microwave or dishwasher. Any child that has complex medical conditions has increased susceptibility to infection. Steps to clean and sterilize equipment are crucial for these children’s overall health.

Any time you mix up formula – those feedings are good to use for 24 hours. Make sure that you label and note of when feedings are mixed and store in the refrigerator until it is time for the feeding. This includes recipes of human milk fortified with formula or formula only recipes. When warming infant feedings, never microwave. Options for warming include a bottle warmer or placing bottle in a warm water bath. When leaving the house with infant feedings, transport in a cooler with ice pack to help ensure the milk/water is kept cold to decrease risk of microbial growth.

When preparing your child’s feedings, follow the recipe on the can or given by your health care provider and check the expiration data prior to preparing. Some children need special feeding recipes to meet their growth goals. Use the scoop in the formula container or measuring utensil provided by your health care provider. Use a safe water source for mixing feedings, this can be tap water or nursery water.

Feeding your child seems like the most basic parenting task, but it can be challenging and complicated for many families. Remembering some of these guidelines of food safety can help ensure that you are doing the best for your child and keeping them safe. Click here to download and print handout from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) our HOW TO PREPARE (cdc.gov)

References:

1. Green Corkins, K., & Shurley, T. (2016). What’s in the Bottle? A Review of Infant Formulas. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 31(6), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533616669362

2. Turck, D. (2012). Safety Aspects in Preparation and Handling of Infant Food. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 60(3), 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338215

3. Green Corkins, K., & Shurley, T. (2016). What’s in the Bottle? A Review of Infant Formulas. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 31(6), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533616669362

4. CDC. (2018, May 7). Infant Formula Preparation and Storage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/infantandtoddlernutrition/formula-feeding/infant-formula-preparation-and-storage.html Accessed August 8th, 2023.

Anna Busenburg, RD, CSP, LD, CLC has been a registered dietitian for the past 11 years and specializes in pediatric nutrition and specifically neonatal nutrition, working in a level IV NICU at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. She has covered inpatient NICU and outpatient NICU follow-up clinic patients.

She has undertaken many projects over the years to help improve patient care and cultivate a culture to support nutrition education. She has been involved in developing a process for utilizing donor breast milk in a 25-bed NICU and she was involved with leading the launch of a breast milk/formula scanning system in a 100-bed NICU. Anna is a certified specialist in pediatrics and has completed the pediatric weight management course. She obtained her Certified Lactation Counselor credential in 2019.

She authored a chapter of the book The Nutrition Communications Guide from AND published in 2020 and published an article in the Pediatric Nutrition Practice Group on RDs Involvement in Infant Feeding Preparation Rooms published in 2019. She currently serves on multiple committees for the Pediatric Nutrition Practice Group and has held various positions within AND on the state and local level. She is also a member of the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. When not busy with work, Anna spends her extra time and energy with her family, which includes her husband, 3 boys, and a Chihuahua.

Hoping for Magic

Published by Anna Taylor on Aug 07, 2023

I didn’t fly to Orange County for the magic of Disney. I flew there in hopes of a magic feeding therapy wand. The truth is, when your child has pediatric feeding disorder (PFD), there’s no such thing as a magic wand. Since 10 months old, we’ve tried various feeding therapists, different approaches, different foods, what feels like everything to get Levi to eat. I’m thankful that he doesn’t have a tube and he takes his calories orally, but I still wish for magic. He will drink only vanilla flavored formula, from a specific cup. He will lick a lollipop, play with food, and take some sips of danimals yogurt smoothies. All of that took over 3 years of slow progress in feeding therapy.

They don’t tell moms about this. There is no instruction manual given out when you have a baby that says, “Hey, your kid might not eat food.” And yes, I am lucky, I know I am lucky. I could be visiting children’s hospitals for much darker challenges; for that I’m immensely grateful. Yet still, I wish for magic. We are coming up on his 4th birthday and I’ve never seen my son eat a birthday cake. I would give him ice cream and cake for every meal, if only he would just eat something… anything.

The trip to Orange County didn’t result in a magic wand. He’s not yet ready for a more intensive therapy program and so we will wait and we will move forward and we will hope. Wait to see if he’s ready in the future, move forward with the current therapists and efforts that have gotten us to the point we are today, hope that one day he will lick the frosting off his birthday cake and maybe even take a bite.