Category: Healthcare Insights

Thickening Breast Milk with Gelmix: New Guides and Handouts

Published by Gelmix on May 18, 2023

This blog post is part of a corporate partnership with Gelmix.

We’re excited to announce new materials, recipes and guides for thickening breast milk with Gelmix Infant Thickener. Our goal with these materials is to improve caregiver education on thickening breast milk with Gelmix, to provide specific recipes and instructions for use, and to answer our most frequently asked questions about preparation.

First, we have a new demonstration video for thickening breast milk in the healthcare setting. Watch Lindsay M. Stevens, MA, CCC-SLP, Medical Facilities Manager for Parapharma Tech, demonstrate how to thicken breast milk. Lindsay discusses best practices for mixing breast milk in the healthcare setting and reviews recipes to achieve slightly thick, mildly thick, and moderately thick consistencies, including small volume recipes.

Additionally, download and print the new guide to Thickening Breast Milk In the Healthcare Setting which includes product information, mixing instructions and recipes for when thickening breast milk is recommended for swallowing difficulties, or for reducing spit-ups, in the healthcare setting.

Finally, we have two new printable patient handouts available. See Printable Guide to Thickening Breast Milk When Recommended for Reducing Spit-Ups and Printable Guide to Thickening Breast Milk When Recommended for Dysphagia for easy to print preparation guidelines for your patient’s specific thickening needs. These patient handouts are also available in Spanish, Guía Imprimible para Espesar Leche Materna Cuando se recomienda para Disfagia and Guía Imprimible para Espesar Leche Materna Cuando se recomienda para reducir el Reflujo.

Have questions or want to learn more? Visit our website to contact us, to request samples or to schedule a webinar in-service!

4 things every pediatric occupational therapist should know

Published by Kate Barlow, OTD, OTR/L, IMH-E on Apr 25, 2023

In honor of occupational therapy month this April, a leader in addressing pediatric feeding disorder shares what OTs can do to improve care for children

By Kate Barlow, OTD, OTR/L, IMH-E

Associate professor of OT at AIC

Early in my occupational therapy career, I worked with a girl who appeared to be in pain every time she ate. She couldn’t speak or communicate well, but it was clear to me that something was wrong.

After checking with her mom, I expressed my concerns to her pediatrician, who instructed me to continue offering milk. It was then that I encouraged the mother to find a developmental pediatrician.

Through evaluation and my conversation with the developmental pediatrician, the girl got a G-tube. She gained weight. Her whole demeanor changed once she was no longer uncomfortable. It was the first time I felt the power of advocating for one of my clients.

As occupational therapists, we always make the best estimates based on our experience and clinical observations.

This was an important lesson for me that I need to trust my gut and be there for my clients. If we as clinicians don’t push for those kids and families, they may not get the care they need.

I’ve been advocating for children with feeding issues ever since.

Feeding is among the main reasons kids are referred to an occupational therapist (OT). And yet, as an OT, I see that the work we do for kids’ feeding issues is an area that needs improvement. With more awareness, education and system-wide assessment tools, all children with feeding issues can access better care.

Universal screening for feeding issues would identify more children who need support earlier

Feeding issues in young children are so common that I believe all children should be screened for feeding concerns. Similarly to school-wide hearing and vision testing, feeding screening should occur in early childhood education centers and schools. We as OTs should advocate for universal screening for feeding issues.

Conservative evaluations estimate that PFD affects more than 1 in 37 children under the age of five in the United States each year. That rate is even higher for children with developmental delays.

A recent study indicates that feeding problems could indicate a developmental delay. Results showed that compared with children who never experienced feeding problems, children who experienced high feeding problems at one or two time points were more than twice as likely to have a delay on all Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) domains. Children who experienced high feeding problems at all three-time points were four or more times as likely to have a delay on all ASQ domains.

OTs and SLPs need a comprehensive screening tool

With the help of a Feeding Matters grant, Dr. Paula Rabaey and I completed a research study, “Investigation of Assessment Tools in the Area of Pediatric Feeding Evaluation: A Mixed Methods Study.” We surveyed 263 pediatric occupational therapists and 182 speech and language pathologists who identified as pediatric feeding therapists. Results showed that OTs and SLPs use various assessment tools. Non-standardized assessment tools were most commonly reported in assessing all four domains of pediatric feeding disorder: medical, nutrition, feeding skill, and psychosocial.

The results indicated a clear need for a standardized assessment tool covering all pediatric feeding disorder domains. The research will be published in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy this summer.

Clinicians need to continue constantly learning

Today’s occupational therapy programs include more pediatric feeding, eating, and swallowing education. In order for occupational therapists to stay up to date on pediatric feeding issues, all feeding therapists need to participate in continuing education courses.

The International PFD Conference from Feeding Matters is an excellent way to level up your pediatric feeding skills knowledge. The conference features the latest research and methods from leaders in the field and attracts clinicians of all levels of experience. The virtual conference is available live Thursday, April 13 through Friday, April 14, and then virtually until Wednesday, May 31.

Feeding therapy needs to be culturally sensitive

We as clinicians do a great job of educating parents, and it is important to be culturally sensitive when working with families. I recently received the infant mental health endorsement – IMH-E – emphasizing the importance of culturally sensitive, relationship-focused practice.

It’s important to consider a family’s cultural norms, home life and income level when recommending what foods children should or shouldn’t eat and how they should approach mealtimes.

We need to ask open-ended questions to access information we might not have even considered and so that families don’t feel judged by any insinuations.

For parents, struggling to feed a child is extremely challenging. It’s our job as clinicians to do everything we can to make that a little easier.

Kate Barlow, OTD, OTR/L, IMH-E® is an associate professor at American International College. She’s also the current ambassador for the CDC’s Learn the Signs. Act Early. program for Massachusetts. She has over 20 years of clinical experience that includes public school practice, early intervention, a pediatric hospital-based outpatient clinic and management. Her areas of clinical expertise are early identification of delays and pediatric feeding.

The Power of Trauma Informed Care for Children with Pediatric Feeding Disorders

Published by Feeding Matters on Apr 05, 2023

Of all the clinical appointments for 15-year-old Maya Roberto over the years, one stands out. Instead of catatonically going through the motions of her echocardiogram, Maya interacted with her cardiologist, even asking questions. Her mother, Dr. Anka Roberto, recalls how shocked she and her doctor were as Maya actively engaged with her cardiologist for the first time.

Noting that his patient, who was five years old at the time, was much more lively, the physician asked what had changed. Roberto, DNP, MPH, APRN, PMHNP-BC told him, she was in trauma therapy and just had an Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) session to help her work through her medical trauma.

The doctor had never heard of it, and was pleasantly surprised with its efficacy.

Today, Roberto uses EMDR to help heal her pediatric patients from trauma as a private practice clinician.

Roberto’s years as a NICU nurse and mother of a child with complex congenital heart defects prepared her for a career in trauma-informed care as an advanced practice nurse. She’s seen personally and professionally how much treating a patient’s trauma as part of the continuum of care can make a difference.

Since birth, Maya’s journey has included multiple open heart surgeries, years of feeding therapy and an NG tube. Roberto knows firsthand how traumatic medical and feeding interventions can have a lasting impact. For children with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD), considering and treating medical trauma can go a long way toward healing children.

Trauma-informed care offers a comprehensive approach that considers emotional and mental well-being to help children and their families affected by PFD. Understanding the impact of trauma on the body and how to navigate it allows families to access an effective care modality.

Defining trauma

Trauma varies for everyone. One major incident or many minor insults can cause trauma. Two people experiencing the same situation can respond entirely differently. One can move forward, while the other carries a lasting physical and emotional imprint. “When I think about trauma, it’s more of an adversity,” says Roberto. “We could have a big trauma, or we can have little things that add up to carry the same weight of a big trauma.”

What matters is how trauma affects the brain and body.

The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study is one of the most comprehensive investigations into the lasting effects of childhood trauma. The longitudinal study showed that early adversity could significantly impact future physical, social and emotional health – as well as lead to early mortality rates.

The pandemic further raised awareness of how trauma can affect mental and physical health.

How the body reacts to trauma

Trauma can profoundly affect the body. Potentially traumatic experiences trigger the body’s “fight or flight” response. In this state, the heart rate increases, and respiration speeds up as the sympathetic nervous system prepares to defend against danger.

The disruption of hormones and enzymes caused by the experience can lead to difficulty regulating temperature, breathing and digestion. The gastric emptying system turns off. It causes constipation, loss of appetite, and/or motility (muscles in the wall of the gut) issues.

“It’s like the fire alarm in the house is going off,” says Roberto. When this happens, the parasympathetic system, sometimes called the “rest and digest” system, stops working.

These acute responses can make an imprint that has long-term effects. Families of children with PFD can mitigate the impact of trauma with support and care. “Trauma leaves a mark, but it’s up to us to find those who can help us get out of being stuck in the triggered cycle,” says Roberto

Understanding trauma-informed care for children with PFD

Trauma-informed care is an approach to support those who have had adverse experiences during their lifetime. Unlike traditional forms of care, which may not be sensitive to traumatic experiences, trauma-informed care recognizes the impact of trauma on an individual’s behavior, thoughts and emotions. The goal is to create a safe space for healing and recovery.Trauma-informed care involves four key components, known as the “Four R’s:

- Realizing how trauma can affect an individual

- Recognizing signs an individual has experienced trauma

- Responding effectively with appropriate interventions

- Resisting re-traumatization by promoting safety, trust, empowerment and collaboration

Understanding these components is essential to effectively support children with PFD, who may be dealing with the long-term effects of traumatic experiences.

Trauma can disrupt eating patterns by causing fear or anxiety around food, leading to refusal or avoidance behaviors. This compounds feeding issues children with PFD already experience.

For children with PFD, trauma-informed care offers a safe way to explore emotions while helping them build positive relationships around eating.

How to navigate the impact of feeding trauma

The effects of trauma on children with PFD can be challenging. What’s traumatic to one child may barely register for another. And the traumatic experience often isn’t even something the child can recall.

This is why it’s crucial to understand each child’s experience, recognize triggers and provide emotional support. Therapeutic interventions such as EMDR can help children reprocess past traumas without needing to talk about them. In her practice, Roberto uses a sand tray and play therapy to help children process previous experiences and feelings.

“They may not have verbal recall and a story to tell, but they remember feeling a certain way,” she says.

A child’s visit to a doctor’s office, for example, can trigger a panic attack because they don’t want to lie on the table, says Roberto. “It’s really because of this unprocessed adversity, which for many people may come from a place of not having control.”

With EMDR, she helps children uncouple the emotional tenacity from that memory.

Benefits of trauma-informed care for children with PFD

Trauma-informed care provides a safe space for families to build trust and better understand how to support their children. Trauma-informed care allows children to explore the experiences that triggered their trauma and develop improved emotional regulation skills. It can also lead to an improved appetite and a willingness to try new foods.

When children get emotional support, they can better articulate their needs to their parents and healthcare team. A therapist can help a child develop practical communication skills and problem-solving techniques. With practice and guidance, these tools allow children facing medical trauma to cope more effectively in difficult situations.

3 ways to support children with feeding trauma

Finding the right resources for trauma-informed care can be challenging, but more resources are developing with a heightened awareness of trauma’s impact.

Focus on the whole family

Roberto says supporting the entire family is key to helping children heal from traumatic events. “Families are like a tree, so if one limb is struggling, the others will start to wither as well.”

Give kids time

Children with medical complications react to stress in the same instinctual way as anyone who senses physical danger. Anyone who’s had to submit their child to medical testing has likely witnessed the fight, flight or freeze response. Roberto recommends slowing down in those moments. “Listen to your kids and give them the time to get there. It’s not about our agenda, as parents or as clinicians. It needs to be about the child’s agenda and providing them with the support they need in the moment.”

Get outside support

Talk to your child’s doctor or pediatrician about what type of care is available in your area and look for mental health providers who specialize in this trauma-informed therapy.

Online resources can also be helpful when seeking out trauma-informed care. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network offers comprehensive information geared toward helping families affected by traumatic events.

Finally, it’s important to remember that although trauma can be difficult, it can be an opportunity to move forward and break the trigger cycle. Roberto says, “We all have our experiences, but we don’t have to let them define us or limit our future possibilities.”

By understanding the trauma children with PFD can experience and working through it with compassion, children can regain control over their lives and reach their full potential.

Anka Roberto, DNP, MPH, APRN, PMHNP-BC an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina Wilmington and has authored book chapters and numerous publications on trauma and resilience. In her private practice, Holistic Healing, PLLC, she provides functional psychiatry care and EMDR therapy to target and reprocess negative life experiences across the lifespan.

Roberto is the keynote speaker at the 10th Annual International PFD Conference on April 13-14. Click here to learn more and register.

Collaboration with Arizona Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program

Published by Feeding Matters on Mar 25, 2023

Recently, Feeding Matters has been working closely with the Arizona Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program. WIC is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) which provides US federal grants to states for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age 5 who are found to be at nutritional risk.

We are excited to share that as a result of our relationship with Arizona WIC, the nutrition coordinators and directors, who are the front line folks supporting families eligible for this program, have been trained on pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). Specifically, Arizona WIC coordinators and directors are trained on the PFD Co-Morbidity and WIC Risk Code spreadsheet so that any time one of them uses one of the codes associated with PFD, they will be prompted to refer the family to Feeding Matters and our Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire. For example, if a child eligible for Arizona WIC is noted as having a genetic or congenital condition, they would be referred to Feeding Matters, specifically to our questionnaire to dig in deeper on their child’s feeding and have a source of support through us.

“This collaboration between the Arizona WIC Program and Feeding Matters ensures that children who have a known condition that often co-occurs with pediatric feeding disorder are more easily identified, identified quickly, and are referred to Feeding Matters to get the support they need.”

Brittany Howard, MS, RDN, CLC (WIC Nutrition Services Administrator)

The collaboration does not end there. They have also added Feeding Matters as a resource to their online education courses that they offer to all of their staff.

We know that PFD impacts one in 37 children under the age of five in the United States and are confident that this partnership will lead to earlier identification and intervention of children with PFD.

FROM THE PFD ALLIANCE: A FOCUS ON EDUCATION

Published by Amy Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP on Mar 22, 2023

As we approach our 10th Annual International PFD Conference, I look forward to learning from expert colleagues about new ideas and strategies that we can use in the care of children with PFD. It comforts me knowing that Feeding Matters has worked diligently to offer content that has been both reviewed for bias and is rooted in evidence. This makes me reflect on the current educational landscape and how it has changed over time.

Thinking back to when I first entered the field (and yes, I’m aging myself), sources for educational content were textbooks and hard copies of journal articles, either arriving in my mailbox or checked out by me at the library. Unfortunately, these old-school sources were nearly outdated by the time they entered my hands. In-person conferences were the only method for me to learn what things were at the cutting edge from my peers and scientists in the field.

Learning today has never been easier! Today’s technology affords endless formats and venues from which we receive information. We have access to first-hand information directly from researchers, clinical experts, and parents. We see examples of different disorders and impairments and clinically validated intervention strategies while standing in line for coffee, or even while on a walk.

Unfortunately, access to everything all the time can be overwhelming, and it may be difficult for a learner to navigate material without a good understanding of its strengths and potential weaknesses. It may seem that everyone is an expert and it’s hard to discern that the information being shared may not be objective, evidence-based, and/or appropriately interpreted. It may be difficult to know which sources to prioritize for one’s learning.

What are my best options? Who am I listening to and what is the underlying evidence? For social media, if one source has more followers than another, is it more likely to be correct or validated? Who is vetting the information? Here are a few pitfalls to keep in mind:

- Saying something with confidence and fancy graphics does not make it sound evidence.

- A greater number of followers does not guarantee information is superior to that from a source with fewer followers.

- Be mindful of individuals who discount or contradict what you have learned to be reliable and clinically validated information.

- Conversely, be mindful of individuals who purport that information is accurate because it’s how it has always been done.

- Is the information based on published studies or other peer-reviewed content?

- Is the source only promoting a product?

- Is the source acting in a professional manner that is ethical and considerate of other opinions?

As we continue to navigate our educational options, consider some of the following suggestions:

- Use multiple sources for learning. Maintain a broad diet of information that includes social media, webinars, and in-person meetings. A broad educational repertoire is always best.

- Dig a little deeper into a new source of information. Learn about your favorite vloggers and what their experience may be. What is their profession and their training? What population of children do they see? Know who you are listening to and trusting to contribute to your clinical journey.

- Think critically about what you’re learning. Does it make sense? Does it continue to enhance your knowledge and practice? Does it contradict well-known evidence?

- Rely on your professional organizations to review the current state of information and evidence and provide experienced perspective on how new ideas may fit into established paradigms.

- Advocate that we need pediatric feeding and swallowing taught at the university level to give everyone a foundation.

We, as a community of PFD providers and families, must lift each other and support each other in our learning to advance the field and the lives of children and families with PFD.

Amy L. Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP

Amy L. Delaney, PhD, CCC-SLP

PFD Alliance Education Chair

best practices within intensive care settings

Published by Erin Ross, PhD, CCC-SLP on Feb 14, 2023

Feeding begins at birth, and for many infants who are born preterm or with medical complications, feeding experiences happen within intensive care units. An international consensus committee has published standards and competencies for best practices within intensive care settings. Currently there are six general areas that are covered by these recommended practices. One is for feeding, eating and nutrition delivery. This is a great resource for people working within intensive care settings with infants – whether in neonatal or cardiac units or other specialty units. There are eleven standards within this area, with multiple competencies within each. Rationale for each standard, along with the body of evidence used to create the standard, are freely accessible. There are also checklists available to measure your current practice.

A common question is “but how do I do this?” Feeding is multi-dimensional and making any changes to current practices can be very overwhelming. Recently a “put into practice” conference produced a White Paper that is also available. I am including this resource for you here.

If you ever wanted to compare where you are (personally or within your unit) with what is possible, this is the place for you. Check it out – and keep coming back. It is currently in the process of being updated with new research and the standards are being evaluated. In fact – you have the opportunity to provide feedback for this process as well – all on the website here.

Does your child need a feeding tube? Here’s what you need to know

Published by Dana Williams, MD on Feb 09, 2023

A pediatric gastroenterologist debunks 4 myths about G-tubes and normalizes a feeding tube for those kids who need it.

Dana Williams, MD, Medical Director, Feeding Disorders Multidisciplinary program; Medical Director, Aerodigestive Digestive Program at Phoenix Children’s Hospital

Dana Williams, MD, Medical Director, Feeding Disorders Multidisciplinary program; Medical Director, Aerodigestive Digestive Program at Phoenix Children’s Hospital

When I see patients who are likely candidates for a G-tube, I can already imagine their lives at home. Days revolve around feedings. Every hour, on the hour, the parents attempt to get an ounce of formula or breastmilk into their little one’s belly. The parents are exhausted, and so are their children. Everyone feels like a failure.

In spite of the struggle, no one wants to bring up a G-tube. So, I do.

As director of a team of physicians, therapists and dietitians at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, I see hundreds of children each year with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). For many of them whose medical complexities make oral eating a struggle, a gastrostomy (G) tube is a key medical intervention. G-tubes help these children develop and thrive, while preventing malnutrition and dehydration.

A G-tube is surgically inserted through the abdominal wall and into the stomach. It’s held in place by an internal device called a balloon. The tube can be used to deliver liquids, purees and medication.

This sounds scarier than it is.

Like any surgical medical intervention, deciding to directly feed a child through a gastrointestinal tube inserted into their stomach is a big decision. For those children who are a good candidate for a G-tube, the benefits of a feeding tube and the risks of not getting one far outweigh any risks.

There are many benefits of getting a G-tube. Some of those include:

- Improved nutrition and hydration: A G-tube provides direct access to the stomach for nutrition, fluids and medication, ensuring children get the nutrition they need.

- Reduced risk of aspiration: A G-tube can reduce the risk of food and liquid entering the lungs, a common problem for children with pediatric feeding disorders.

- Increased independence: Children with G-tubes can engage in activities they enjoy without the stress of constantly worrying about eating or drinking.

- Better sleep: A G-tube can provide continuous nutrition and hydration overnight, leading to better sleep and improved overall health.

- Eased caregiver burden: Parents get relief from constantly trying to provide adequate nutrition and hydration.

- Improved weight gain and development: Children with a G-tube often see improved weight gain, leading to better overall health.

- Comfort: Removing the alternative temporary nasal tube can make it more comfortable for a child to eat. Depending on each child’s medical journey, they may be more likely to eat when they don’t have hardware in their noses.

Still, many parents who consider a G-tube for their children can feel like a failure. The truth is the opposite. Feeding isn’t something parents or doctors or anybody can control. If a child doesn’t want to eat, or they can’t eat, then there is nothing anyone can do to make them. Of course, this can change over time with multiple levels of support. But the parents of these children haven’t failed.

Debunking 4 major myths about G-tubes

Most of the time that parents express hesitation about the G-tube, it’s because of a fear of one or more of four common myths. Talking about the reality of what a G-tube will mean for a child and the family helps parents make an informed decision.

Myth #1: A G-tube is permanent

A G-tube is a temporary solution to supplement or replace oral eating and drinking. I have countless patients living healthy lives after the removal of their G-tubes who will attest to that fact.

How long each patient needs a G-tube and whether they’re receiving all or some nutrition through the tube depends on each child’s needs. When a family is deciding about G-tube surgery, we discuss the anticipated use. In many cases, a G-tube can supplement – rather than replace – oral eating.

We also discuss the process for removing a G-tube for those kids who can eat fully orally one day.

Myth #2: Infection is common with a G-tube

Infections do occur for some people with a G-tube, but they’re not common. Some children are more sensitive, and there is no way to predict that. For most people, the channel for the G-tube heals nicely. Similarly to an ear piercing, it becomes epithelialized so that the tube can comfortably pass through the area. We monitor the insertion hole and mitigate the risk of infection by teaching parents and older children how to clean the area.

Myth #3: Kids can’t eat regular food with a G-tube

The majority of kids with G-tubes in our practice also eat orally. This varies for each child, depending on their medical issues. Most children I see even take pleasure in oral food. The G-tube is an important tool that gives children time to develop the ability to eat on their own terms.

Myth #4: A G-tube means kids won’t be motivated to eat orally

While there is some truth to this myth, it’s not entirely accurate. For many kids with PFD, it doesn’t take much for them to feel full. This is why we individualize treatment so that each child receives the amount they need. Children can still learn hunger cues and get exposed to meal time routines.

What is a sign of success for a child with a feeding tube?

Just as the treatment plan for every child with a feeding tube is different, success also varies. To me, the main signifier of success is when the patient and family are in close conversation with their doctor. Every journey is different, but having a team of the right medical provider matters. It’s not up to parents to walk this journey alone.

Beyond that, any step forward for a child is success. Some examples are as follows:

- A child who aspirates due to a medical condition safely learns to taste some food and enjoy family meals.

- A child slowly learns to eat orally through feeding therapy post heart surgery.

- A child who outgrows some allergies and tries more foods.

- A young adult who goes off to college even though he still only eats seven foods.

Parents of children with pediatric feeding disorder no doubt feel responsible for ensuring their children get the nutrition they need to grow and develop. For those children who are good candidates for a feeding tube, a G-tube is an important tool to help them along their feeding journey.

Hadyn Van der Molen has had a G-tube since he was nine months old. His mom, Heidi, program manager for Feeding Matters, recalls feeding Hadyn around the clock with a 2-oz. bottle. The only time he’d ingest it was when he was sleeping.

Mighty Milk or Diet Diversity?

Published by Raquel Durban, MS, RD, LDN on Feb 01, 2023

This blog post is published as part of a paid partnership between Feeding Matters and Reckitt Mead Johnson. Learn more about our corporate partnership program and ethical standards for collaboration.

Food shopping has evolved over the years. Long gone are the days of only cow’s milk or soy milk. Now it seems there is milk made from every type of plant! You will likely find yourself questioning, “which is best for me?” or “is there a better option to use as a replacement in cooking or baking?”.

The range of alternative milk beverages includes almond, cashew, soy, coconut, pea, oat, walnut, flax, hemp, macadamia, and rice – as well as what seems like a new option each week!

The nutrients are just as varied as the plants from which they are derived. The question is, “Which milk is best for ME?” because your nutrition needs, and taste preferences will differ from another person’s.

The nutrients in cow’s milk are protein, calcium, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin B12, riboflavin, niacin, phosphorous, pantothenic acid, zinc, selenium, iodine, and potassium.

Avoiding cow’s milk does not mean you have to miss out on its great nutrition! Other sources of these nutrients include:

- Protein: meats, beans, some plant-based milk.

- Vitamin A: beef liver, sweet potato, carrots, cantaloupe, red bell peppers, fortified cereals, mango, spinach.

- Vitamin b12: beef liver, clams, tuna, fortified nutritional yeast, salmon, beef.

- Riboflavin: beef liver, fortified breakfast cereals, beef, clams, almonds.

- Niacin: beef liver, chicken or turkey breast, prepared marinara sauce, salmon, tuna, pork, beef, rice, fortified breakfast cereals, russet potato.

- Phosphorus: salmon, scallops, chicken breast, lentils, beef, cashews, russet potato, kidney beans, brown rice, peas, oats, egg.

- Pantothenic acid: beef liver, fortified breakfast cereal, shitake mushrooms, sunflower seeds, chicken breast, tuna, avocado.

- Zinc: oysters, beef, crab, lobster, pork, baked beans, fortified breakfast cereals, dark meat chicken, pumpkin seeds, cashews, chickpeas.

- Selenium: Brazil nuts, tuna, halibut, sardine, pork, shrimp, enriched pasta, beef, turkey, chicken, egg, and brown rice.

- Iodine: most enriched grains and iodized salt.

- Potassium: apricot, lentils, squash, prunes, raisins, potato, kidney beans, orange juice, soy, banana, chicken breast, salmon.

Here are some tips when shopping for your new favorite:

- Choose unsweetened varieties with little to no added sugar. Those labeled “original” often contain large amounts of added sugar that add up quickly.

- If using plant-based milk to replace cow’s milk, choose one fortified with calcium and vitamin D.

- Children ages 1-2 should receive full-fat versions with a nutrient content similar to whole cow’s milk. Adults, however, can consider low-fat and fat-free versions.

Reference: https://ods.od.nih.gov/

Raquel Durban, MS, RD, LDN is a registered dietitian specializing in the dietary management of families with food allergies. She received her master of science degree in nutrition from the University of Maryland and completed a nutrition internship at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. As a recognized authority on the dietary and nutritional management of food allergies, she is a frequently invited speaker at allergy and immunology conferences and has the pleasurer of precepting dietetic interns. Ms. Durban has contributed her expertise to peer-reviewed publications and continuing education programs.

Ms. Durban is a steering committee member and cochairs the internship program of the International Network of Dietitians and Nutritionists in Allergy and serves on the Medical Advisory Board of the International Association or Food Protein Enterocolitis. She plays and active role in the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI). She serves on the organizations’ numerous committees, collaborating with other health care professionals and patient advocacy groups to improve quality of life and advance understanding of families living with the challenges of food allergies.

From pediatric weight gains and losses to restricted diets for food allergy and disease management, she does not believe there is a one-size-fits-all answer for success. She will work to find the best balance of meeting nutritional needs with lifestyle demands and ensure collaboration with other members of the care team.

Picky Eating: Just a phase or cause for greater concern?

Published by Cuyler Romeo, M.O.T., OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC on Jan 30, 2023

How to know if your child will outgrow picky eating. Plus, how to survive mealtimes with the pickiest palates.

From birth, the majority of time you spend with your infants and young children revolves around food. Children eat a minimum of six times a day. It takes hours to prepare food, feed kids and clean up.

This means that when feeding becomes a challenge, parents can feel like a failure. That was the case for Natalie Peterson, mom of Easton.

When Natalie introduced Easton to solid foods at 4.5 months, she immediately knew something was off. “How he reacted felt different. I brushed it off initially but I think deep down in my gut, that mom instinct knew something was different.”

They tried again and ran into that same reaction. Easton pushed the food away, refused it and even became angry. “It was incredibly isolating. It felt like we had failed him.”

Easton was the first child in the U.S. to be diagnosed with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD).

And Natalie certainly wasn’t the only parent to feel anxiety, frustration and shame over picky eating.

How common is picky eating?

Picky eating is a common disorder during childhood. According to Dr. Kay Toomey, pediatric psychologist and member of Feeding Matters, a variety of studies across the world suggest that approximately one-fourth to one-third of children on average will struggle with some type of feeding and/or growth issue in their first decade.

Picky eating can look similar, but the causes vary. Many toddlers experience a phase of picky eating when they need fewer calories than during months when they were growing faster. That decrease in appetite coupled with their curiosity about boundaries can lead to fussy eating.

It’s when this persists or becomes more extreme that picky eating could be a sign of another underlying condition, such as pediatric feeding disorder (PFD).

What is considered picky eating?

According to Dr. Toomey, the operational definition of picky eating is children who demonstrate either transient or more extended challenges (up to 2 years duration). She outlined the following feeding and eating patterns in a presentation for Feeding Matters:

- Strong preferences

- Limited variety

- A restricted number of foods they will eat.

- Avoiding new foods

- Refusing the “right” foods or the “right” amounts

- Getting more upset than peers

- Requiring a special meal by their parents

- May eat differently in different contexts

How can I help my child with picky eating?

While many children will be picky eaters in spite of parents’ best efforts, there are a few ways to encourage children to eat better.

Following are a few ideas you can try if you’re experiencing stressful mealtimes:

Establish a mealtime routine. Children find comfort and confidence in a predictable routine. This will depend on the needs of your family. There’s no right answer.

Set up loving, appropriate boundaries. I don’t expect a toddler to stay seated at the table for 30 minutes, but I would expect a two year old to eat at the table for 10 minutes instead of taking a bite from the table and running around. If your child is on the autism spectrum, this may not be an appropriate expectation.

Harness the power of hunger. You’re more likely to have successful mealtimes if your kids come to the table hungry. Having a predictable schedule will help.

Make meal time social. Eating with your child, enjoying foods together and modeling appropriate mealtime behavior can help.

Limit the introduction to new foods. New foods are an important way to teach your child about healthy eating. Introduce something new together with something familiar to help your child acclimate.

How long does picky eating last?

Among children who are picky eaters, only about one-third to one-half will outgrow their picky eating within two to three years. Three to 10 percent of infants and children have significant, persistent feeding and/or growth problems over time. These are the children who have pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) and need feeding treatment.

When should I be worried about picky eating?

While picky eating is a common behavior among children, extreme picky eating can lead to nutrient deficiencies or poor growth.

Extreme picky eating is a sign of PFD if a child displays some of the following characteristics:

- Extreme food selectivity: based on texture, color and taste

- Food refusal: gagging, vomiting, hitting, crying

- Limited appetite

- Poor weight or failure to gain weight

- Delayed or dysfunctional eating skills

- Disruptive mealtime behavior

- Eats differently in different environments

- Negatively impacts family functioning

Children with PFD need medical intervention to manage the diagnosis. When a child isn’t eating or drinking the quantity or the variety they need to grow and be healthy, it’s not just because they are being “fussy.” There is usually an underlying reason. Talk to your pediatrician about PFD and check out our family roadmap for support.

Cuyler Romeo is director of strategic initiatives at Feeding Matters and a clinician at Banner-University Medical Center’s NICU.

Premature births on the rise, leading to more pediatric feeding disorders

Published by Feeding Matters on Jan 24, 2023

Here’s what you need to know about the stats on premature births in the U.S., its causes and what we can do about it.

For most families of babies in the NICU, a premature birth comes as a total surprise. That’s because nearly 90 percent of babies in the U.S. are born at gestation, after 37 weeks. But an increasing number of newborns are born prematurely, according to the March of Dimes 2022 Report Card, released in November.

A rising rate of premature births results in an increasing number of babies with feeding issues. Those children who develop long-term feeding issues are at risk of having a pediatric feeding disorder, or PFD.

With a rate of 10.4-10.7 percent of babies born prior to 37 weeks in the U.S. in 2021, the March of Dimes gave an abysmal preterm birth grade of D+. It’s a rate that’s .4 percent higher than the previous year and the highest recorded rate since 2007.

Globally, the rate of preterm birth ranges from 5 to 18 percent of babies born, according to the W.H.O.

The number of weeks babies are born prior to full term and the newborn’s health will determine how long families spend waiting for their babies’ release from the NICU. In an average week in the U.S., nearly 70,000 babies are born. Over 7,000 of them are premature.

Depending on how premature a baby is and problems that may have occurred during their stay in the NICU, most of those babies eventually go on to reach all the milestones of their full-term peers. But this unexpected start is distressing for parents. The biggest challenge for most of the babies is feeding.

NICU staff spend most of their time supporting preterm babies’ nutrition needs, says Dr. Matt Abrams, a neonatologist with Arizona Neonatology at HonorHealth Scottsdale Shea Medical Center. “Feeding difficulty is one of the most common and challenging things we deal with in the NICU. Although people think of preterm babies as having breathing issues, most of the time in the NICU, we spend on nutrition and transitioning to oral feedings.”

The duration of a preemie’s feeding challenges is inversely related to their gestational age. The more pre-term the baby, the more likely they are to take longer to mature. Upon release from the NICU, Dr. Abrams says most of these babies will start to eat normally after a few weeks at home. But some of them will continue to struggle with feeding challenges.

The annual prevalence of PFD in the United States is between 1:23 and 1:37 children under the age of 5. This is higher than other more well-known childhood conditions such as autism (1:54) and cerebral palsy (1:323). Not all children diagnosed with PFD were once preemies, but many of them were.

Causes of preterm births in the U.S.

There are several variables that determine whether or not a baby is born prematurely. These include the following:

- The age and health of the mother

- Contraction of COVID-19 while pregnant

- Obesity and hypertension

- Multiple gestation

- Proximity to a hospital

- Race

- Poverty

- Access to prenatal care

- Smoking/drinking/drug use

Among other contributing factors such as access to prenatal care, Dr. Abrams sees fertility treatment as a key reason for more premature births. “Some places are not being judicious about how many embryos they’re implanting, which leads to higher rates of multiple gestations and therefore increases risk of premature birth,” says Dr. Abrams.

Whatever the cause, an early delivery is a challenge and a shock for parents. This was the case for Paula Benzing, a mom of three in Mesa, Arizona.

Paula visited her doctor for stomach pain, indigestion and heartburn. These symptoms are common in pregnancy, but Paula’s case was severe. Her doctor ordered blood work, and she was diagnosed with HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count.

Paula had a cesarean section right away, at 28 weeks. Her son, Isaac, who’s now 13, was in the NICU for 3.5 months. Much of that time, and for months afterward, was spent on feeding therapy and bottle therapy.

Paula’s second child was born at term. With her third, 6-year-old Penny, Paula once again had to deliver at 28 weeks. Penny needed even more feeding support than Isaac. She came home from the NICU with a feeding tube, which was replaced by a g-tube at six months.

Paula’s day revolved around feeding Penny, all while chasing a two-year-old toddler. Every three hours she’d thicken formula to attempt to feed Penny orally – knowing she wasn’t likely to take it. She’d toss out that formula and instead mix a thinner version for the g-tube instead. “No matter how slow we did it, most of the time she’d throw up. I was a big ball of stress,” says Paula.

Dr. Abrams sees countless anxious parents in the NICU who stress over their babies’ feeding progress. “Eating is social, so it’s very distressing to families when kids can’t do that. At the same time, it’s not very tangible. When babies are on a ventilator or they have something more concrete, families cope much better than when their baby is totally healthy but having feeding issues. They must be patient to see how things evolve over time.”

The increase in preterm births in the U.S. means more and more families are having to be patient. But, not all families are affected equally.

Race and geography matter for maternal health

In the March of Dimes report card, some states scored worse than others. Nine states and one territory, including seven states in the Southeastern United States, received a grade of F. Only one state, Vermont, received a A- state-level preterm birth rate, with the lowest preterm birth rate at 8 percent.

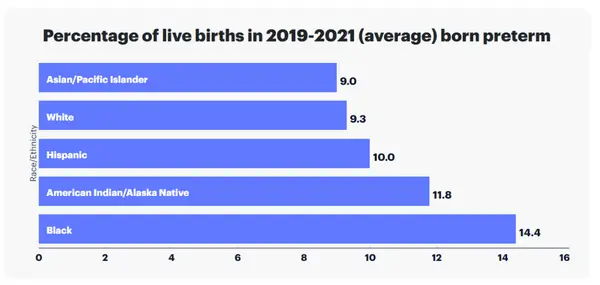

Preterm birth rate also varied by race and ethnicity in the United States. Preterm birth rate among Black women is 52 percent higher than the rate among all other women, according to the report.

Within states, the likelihood of preterm birth varies as well, depending on location, economics and ethnicity.

Impact preterm birth has on children and families

A preterm birth is often stressful for parents during their baby’s stay in the NICU. Juggling work and home responsibilities compounds that anxiety. Preemies are typically sent home with overwhelming and time consuming care instructions that can include multiple care appointments.

Parents of children who require longer support or have additional diagnosis, like pediatric feeding disorder, carry an even heavier burden.

According to a nationwide survey of insured families conducted by Feeding Matters:

- 76% of respondents reported that PFD results in at least a moderate financial burden for their family

- 33% of respondents had to leave full-time employment

- 23% turned down a job offer/raise in pay/more hours per week

- 47% reported depression

Overall, the lifetime average income loss to a family is $125,645.

The stress for a family can be tremendous for the duration of a child’s feeding challenges. Denise Hoffman is a pediatric occupational therapist and clinical assistant professor at Indiana University South Bend. While she was uniquely positioned to support her child who was born prematurely and had feeding issues, she still faced massive challenges. She had the luxury of quitting her job and made breastfeeding her son, Trey, a full time job. She describes feeding him and practicing feeding therapy a 24/7 job. Still, she recalls that he’d only manage to eat an ounce in a feeding.

Besides the time commitment this requires, the stress takes its toll. “As a mother your instinct is to feed your kid, and when you can’t, you feel like a failure,” she says.

Denise was grateful that she could stay home with her son and his older brother. She also had help from family. Many Americans facing similar struggles aren’t as fortunate.

How the U.S. can decrease the rate of preterm births

Prenatal care helps prevent preterm births. But Dr. Matt Abrams argues intervention needs to take place even before pregnancy.

“I think the work must be done before pregnancy by reducing complications related to obesity, diabetes and hypertension and by having fertility treatment that is judicious about who is a good candidate and how many embryos are implanted. Once you’re pregnant, there are few ways to reduce preterm birth other than good prenatal care. In rural areas of the country, it means increasing access to telemedicine.”

The March of Dimes advocates for much-needed legislation and funding that can improve maternal and infant health outcomes. Click here to read about their campaign #BlanketforChange to advocate for health equity for moms and babies.

They say it takes a village to raise a child. Turns out, it takes the will of a whole country to support newborns and their families.

Feeding Matters is the first organization in the world uniting families, healthcare professionals, and the broader community to improve the system of care for children with pediatric feeding disorder through advocacy, education, support, and research.