Category: ARFID

PFD Story- Baking with the Besties

Published by Christina Van Ditto on Mar 28, 2024

As parents of children with medical complexities and special needs, we parent as clinicians. We are responsible for care and carryover that often resembles a therapeutic and medical model.

When Gia was a toddler, I ran our home like one big therapy session. About six months into it, she was miserable and so was I. This approach wasn’t working for either of us. So, I ditched it and committed to simply being Gia’s mom. I leaned into what feels natural to me, a method I refer to as, “instinctual parenting”.

When it came to language and regulation, as a former dancer, I used movement and dance to encourage verbalization, soothe, and bond with my daughter.

And when Gia didn’t respond to intensive therapies for ARFID and she began her journey of being tube fed, I leaned into what felt natural to me once more.

I put on a show. Literally.

A supportive baking show

Welcome to Baking with the Besties, where fashion meets inclusive baking. A baking show that I have been putting on for my daughter for several years now.

The planning process is nothing short of involved.

Each month’s theme is carefully considered. In addition, there’s the recipe which needs to be gluten and dairy free and relevant to the theme. I consider the sensory profile of each ingredient that we’re using and handling. Sensory supports that are always accessible to Gia are a bowl of warm water and dry towel when she needs relief from a tactile sensation and headphones for the times we use the mixer.

And there’s the fashion, which is not superficial.

Again, this approach is instinctual to me. To me, fashion is a form of self-expression and I am incredibly passionate about accessible and adaptive fashion, subsequently. Imagine my surprise when Gia, 4 years old at the time, refused to change out of a Frozen t-shirt for three months. I even had to bathe her in it. Through this experience, I learned that Gia’s insistence on sameness was her go-to, functional way to manage her anxiety.

Therefore, I use fashion as a tool to encourage cognitive flexibility in Gia, I call this “Flexibility through fashion”. She is able to transition in and out of outfits and costumes that we wear with joy, excitement, and interest. In addition, I design and create custom chef hats. Nowadays, we have more of these glamorous and over the top chef hats than I can count. I’m always surprised as to how beautiful they come out and just cannot wait to show Gia the finished product that I make specifically for her. It doesn’t end there. Sometimes the monthly theme calls for us to wear wigs. Which challenges her sensory assimilation in a super fun, non-threatening way.

Bringing awareness and acceptance

When it comes to exploring the food that we’re handling, Gia is never expected or pressured to eat what we make. Nearly two years in, during our first few episodes Gia was repulsed by the smell of flour. Her olfactory is super sensitive and at that time, was working overtime as her body was healing from nutritional deficiencies.

When disinterest sets in, it isn’t uncommon for me to use Gia’s special interests to encourage her to interact and engage. Small figurines, lined up in batter, make regular appearances in our episodes.

We research and learn the person or the topic that we’re celebrating with food that month. Most importantly, we celebrate one another. And enjoy the messes we make along the way. There’s laughing, crying, and stimming. We bring awareness to feeding differences and acceptance to neurological differences.

Our therapy room is our kitchen and the work is done at our baking benches. Gia has her own drawers filled with her own cook books, measuring cups and plastic safe cutlery. Another strategy and invitation for a person that has never used cutlery to eat … she’s 8 years old. We have cake stands that spin, she’s a big fan of that. As a visual learner and hyperlexic, Gia loves and thrives with visuals, so we love a good recipe in print. And the cook book stand often doubles as a holder for her transitional book.

Supporting Gia

Gia has one safe food. And one safe beverage. Brand specific and presented in only a few variations, with a ritual. Gia moved from an NG to a more long term solution to meet her nutritional needs of a Mic-key button.

There’s no shame in our game. I’m just a mom baking with her daughter. Who happens to be neurodivergent and tube fed.

Gia is learning that food is more than what we put in our mouths. It brings people together, oftentimes the people we love most. We are building happy memories and learning food is a gift to give. Food represents mealtimes where everyone has a place at the table, regardless of what’s on or not on our plates. Essentially, she is building positive neuro associations with food and eating.

BWTB’s truly is more than a baking show we record from the comfort of our ASD friendly kitchen. Oftentimes laughing before we even hit the record button, It has helped to reduce the stress and pressure around eating and mealtime for us both. A natural modality, I have used my creativity to support Gia in her recovery and help to alleviate caregiver stress, simultaneously.

A journey beyond the kitchen

A part of my journey as a caregiver and food partner to my daughter has been letting go of expectations and standards. Eating and pediatric feeding disorders, different abilities, and medical complexities can be disempowering. I am not minimizing the worry or overwhelm that we justifiably experience as parents and caregivers. Gia has never put a morsel of meat in her mouth. She would be unable to safely masticate a chip or fibrous, non-pureed fruit or vegetable, at this time. But Gia is on her own time-line. And I am finally at peace with that. I felt so much urgency at the start of our journey. A familiar pang I felt in regard to her developing language and learning to toilet. Now, I understand and have embraced that we are not in race. My child is building new pathways, developing and strengthening her sensory muscles, working through debilitating anxiety and cognitive flexibility. And the whole while, I never take off my mom hat. Or my mom chef hat, that is.

Recovery is a journey. And I’m here for it. I am more than my daughter’s food partner, I am her partner in life.

This is Gia’s journey with food, only it’s more of a screenplay than a story and the last Act has yet to be written.

Stay tuned.

Christina Van Ditto is a PFD and ARFID caregiver, advocate, writer and public speaker.

Pediatric Feeding Disorder to ARFID: A Young Child’s Journey

Published by Feeding Matters on Jun 26, 2023

Not long after Alexandra Marcy’s third child was born, she knew something was wrong with her eating. From the start, her daughter, Emerson, wasn’t latching properly. “I was told at the hospital that her latching would come naturally. We tried for a few days, and I knew it wasn’t normal,” she says.

It wasn’t long before Emerson’s diapers were dry.

A doula friend suggested Emerson might have a tongue tie, making it hard for her to latch. Not only did she indeed have a tongue tie, but she also had a lip tie and a buccal tie – a cheek tie that results from an abnormally tight frenum. Emerson underwent a laser procedure on all three, and Alexandra started using a nipple shield while breastfeeding.

Even then, says Alexandra, “She’d get a little bit of milk but never enough. Any time I tried to nurse her, she’d scream.”

Those early feedings began a four-year feeding journey that’s still developing today. What began as a medical feeding issue then is today a psychological issue. The Marcy family continues to navigate the uncertain path between pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) and Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID).

Click here to read about PFD and ARFID and how the two diagnoses can overlap.

See here why misdiagnosing PFD and ARFID can do more harm than good.

Following is their story.

One young child’s journey from PFD to ARFID

Alexandra gave up on breastfeeding early and instead pumped milk for Emerson. The baby never took more than an ounce at a time. Even then, Emerson would spill milk out of her mouth and gag. Like many parents of children with PFD, Alexandra spent most of her time around the clock pumping and feeding her daughter.

Emerson also sounded congested all the time. Her pediatrician assured Alexandra this was normal.

Alexandra wasn’t convinced, and at three months, baby Emerson was breathing strangely and seemed limp. It was RSV season, but a swab and an X-ray seemed fine. But Emerson hadn’t gained weight since her previous pediatric appointment. When Alexandra returned a week later for a weigh-in, the baby lost a few ounces. The pediatrician recommended Alexandra supplement with formula. He suggested her breast milk wasn’t fatty enough. Emerson lost more weight even with formula.

They ended up at Phoenix Children’s Hospital (PCH) when Emerson was four months old. “I saw so many doctors, who all thought her breathing and eating will be fine. We were there for over a week without any answers,” says Alexandra.

It wasn’t until Alexandra, who worked in a therapy clinic, managed to connect with a feeding therapist from her team that she got some answers. She looked over Emerson’s original X-ray of her lungs from when Alexandra suspected she had RSV and saw shadows in the image. A second X-ray showed the shadowing had gotten worse since then. This was a sign the baby was aspirating.

The family turned to a gastrointestinal doctor for answers. Emerson was diagnosed with allergies and started an animos-based formula, which helped. “Still, though, she was a terrible eater. It was hard to get 4-oz. into her,” says Alexandra.

It seemed like any time Emerson would make some feeding progress with her feeding therapist, she would get an upper respiratory infection or rotavirus that would set her back.

Emerson got an NG tube to build up her strength. The NG tube helped the baby gain weight, but Alexandra still remembers it as traumatic. “Any time it came out, I’d have to have my eight-year-old hold her down while I put it back in her. It felt crazy and sad.”

Eventually, Emerson was diagnosed with:

Type 2 laryngeal cleft: An abnormal opening between her larynx and the esophagus that allowed food to enter her lungs

Tracheobronchomalacia: Her weak tracheal or bronchial tubes would collapse any time she ate or cried.

Dysphagia

“Finally, we had answers, but no way to fix it,” says Alexandra.

At eight months, Emerson transitioned to a G-tube as a long-term feeding solution. “This was so much better because I could see her beautiful face. She wasn’t gagging and throwing up,” says Alexandra.

The G-tube even helped Emerson overcome some food aversions to try solids. Alexandra added her to the months-long waiting list to get into the feeding program at PCH.

Thanks to the family’s hard work, Emerson progressed and eventually got into the feeding program. But at age three, she started to regress again. She stopped eating most of what her parents offered, accepting only four foods.

Even after three weeks in an intensive feeding therapy program at PCH, Emerson wasn’t progressing. At that point, all her medical issues had been addressed and resolved.

The hospital team suggested Emerson see a psychologist, who thought the three-year-old could have ARFID. Eventually, Emerson was diagnosed with ARFID and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). She was young for both psychological diagnoses, but a child psychologist and a child psychiatrist agreed.

Emerson was treated with EMDR therapy to help her reprocess the medical trauma she experienced as a baby and toddler. “Any time she eats, she doesn’t want to feel pain, so this makes her restrictive and gives her intrusive OCD thoughts,” says Alexandra.

A psychiatrist who has worked with many children with PFD and ARFID prescribed medication, helping Emerson be more open to new foods and eat more. Things have gotten easier, but still, says Alexandra, their journey isn’t over. “She just doesn’t care about food. She doesn’t act hungry, and I have to remind her to eat.”

Alexandra hopes sharing her family’s story will help others navigate a similar path.

For more information, visit Feeding Matters’ resource page: PFD and ARFID. If you are a parent needing support, check out our family support resources .

PFD, ARFID or both?

Published by Will Sharp, PhD on Jun 12, 2023

Developing common terminology for children with PFD and ARFID is key to improving diagnosis and treatment

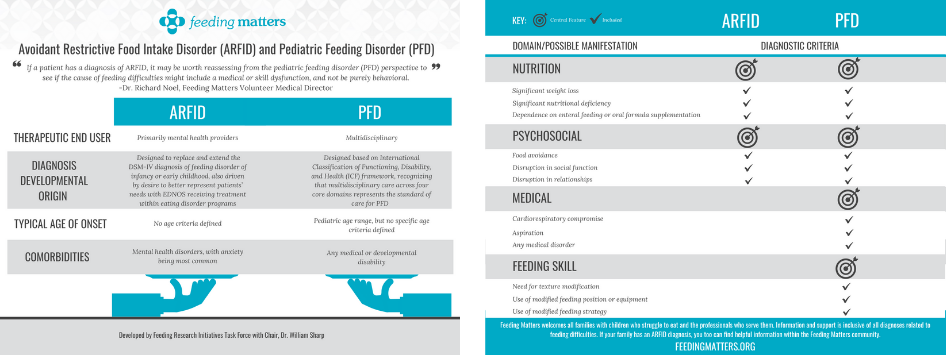

By William Sharp, PhD is a behavioral psychologist and director at theChildren’s Multidisciplinary Feeding Program at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Naming pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) as a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code in 2020 provided much-needed clarity for clinicians and parents alike. For the first time, parents whose children faced feeding problems caused by medical and/or developmental conditions, such as premature birth or autism, could identify and discuss their struggle. Primary care physicians, often called upon to identify PFD, could use the diagnosis to facilitate referrals. Clinicians had an insurance billing code to use when providing care. When everyone shares a common language, finding solutions and improving outcomes becomes easier. But confusion remains. Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is also a relatively new psychiatric diagnosis, introduced in 2013 in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5 code. ARFID describes food restriction and avoidance that may occur in infancy and early childhood. It overlaps with PFD, which is confusing for families and clinicians. The question is, when is ARFID actually PFD? And do you treat ARFID differently if a child has a history of PFD? Defining the differences and similarities between PFD and ARFID is the next step in clarifying both diagnoses and improving support for children who experience them.Defining ARFID and PFD

Let’s break down the diagnoses, their similarities and differences. ARFID is a mental health diagnosis describing children with feeding problems and related nutritional risk or deficiency without coincident body image problems, as seen in anorexia. Children with ARFID have one or more of four symptoms:- Weight loss

- Significant nutritional deficiency

- Dependence on internal feeding or nutritional supplements

- Significant interference with your day-to-day functioning

- Medical

- Nutrition

- Feeding skill

- Psychosocial

Defining the gray area between ARFID vs. PFD matters

Intensive, multidisciplinary pediatric feeding centers like at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta are rare, with only approximately 16 comprehensive clinics in the U.S. Altogether, they provide intensive intervention for about 700 kids yearly. Conservative evaluations estimate that PFD affects more than 1 in 37 children under five in the U.S. annually. Instead of accessing support at feeding centers, children with feeding issues may land on the doorsteps of eating disorder clinics. Sometimes these children have PFD that was never treated at a young age. Here’s an example of a typical child in our feeding clinic: A child was born prematurely and required intubated to aid with breathing. She also had poor motor skills and required a feeding tube to meet all her nutritional needs. She remained on the feeding tube throughout infancy due to concerns with aspiration and swallow safety. At this point, she was diagnosed with PFD. Once medically cleared for oral feeding, a speech therapist worked with the child to introduce pureed food. However, she refused many foods, limiting the volume and variety of food she would eat. These behaviors worsened overtime. After two years of weekly feeding therapy, she was referred to a multidisciplinary feeding program, where she was diagnosed by a psychologist with ARFID. Like the patient above, ARFID may begin not as psychological diagnosis. Instead, it’s a response to a medical complexity. A physical challenge became a behavioral challenge. Supporting this child and millions like her means addressing both. This also highlights the potential connection between PFD and ARFID, a connection that caregivers and clinicians may find confusing. Coming together to improve care for children with PFD and ARFID

Coming together to improve care for children with PFD and ARFID

Ensuring the needs of children with PFD and ARFID are being met requires coming together as a community of multidisciplinary clinicians treating them.

As part of the Feeding Matters research task force, we conducted a national survey of 650 providers assessing and treating PFD. It’s the largest survey of its kind, and responses are key to identifying existing support and current needs. We expect to publish survey results this summer 2023.

Armed with that information, we can start to develop common terminology for PFD and ARFID. Together with Feeding Matters, our Feeding Clinic at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and Emory University will host a summit in August to begin this conversation.

One possible clarifying solution is to have subcategories of both diagnoses. Subtypes would root each diagnosis in a patient’s history. This would mean children fall into four categories:

- PFD

- ARFID

- PFD with an ARFID subtype

- ARFID with a PFD subtype

William Sharp, PhD is a behavioral psychiatrist and director of Children’s Multidisciplinary Feeding Program at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. He’s a medical advisor to Feeding Matters and is helping shape the PFD and ARFID conversation.

Accurately Diagnosing PFD and ARFID: Why Misdiagnosis Can Do More Harm Than Good

Published by Jaclyn Pederson, MHI on Apr 21, 2023

I recently heard about a distraught mother of an eight-year-old, whose daughter spent time in an eating disorder clinic. She was diagnosed with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), which is often described as extreme picky eating.

After completing the program, her child showed no improvement and even developed more anxiety around eating. Minutes into the conversation, it was clear that this child most likely had undiagnosed pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). An effective assessment and treatment plan must address more than psychiatric and behavior therapy for any child who has been identified as having concerns with feeding.

As CEO of Feeding Matters, I hear these stories regularly.

In the two years since PFD became an official ICD diagnostic code, I’ve seen hundreds of families in the U.S. and around the globe become more informed and able to access better care for their children. Naming the issue that has many symptoms and requires a multidisciplinary approach has given families tremendous relief and support.

But, our work is far from over.

What happens when PFD is mistaken for an eating disorder

Children as young as one are being diagnosed with ARFID when they actually have PFD. In plain terms, this means children with a medical and multidisciplinary feeding disorder are instead diagnosed as having a psychiatric condition.

The actual cause of children’s limited intake or picky eating is sometimes overlooked. It’s nearly impossible to resolve a mental or behavioral eating issue without first looking into the other domains that contribute to eating function, including medical and feeding skills.

I’ve seen with my infant how eating is a learned behavior. My baby has a cow’s milk protein allergy and challenges with his suck and anatomy. Once we identified his issues, we switched formulas and found a better bottle for his anatomy. Even then, it still took a month for him to develop the necessary feeding skills to consume greater than one ounce per feeding. My child only had a feeding challenge, and was not diagnosed with PFD. Still, this shows how a holistic assessment and treatment plan that considers the interplay of the four domains of PFD allows for targeted interventions that match each child’s unique needs. With early identification and treatment of medical and feeding skill dysfunction, the hope is that the long term psychosocial impact can be reduced.

The longer feeding challenges go untreated, the greater the psycho-social impact. As children get older, psychological difficulties become the primary drive for feeding dysfunction and the problem evolves from a developmental one to a mental health condition.

Why PFD is often misdiagnosed as ARFID

ARFID is a mental health diagnosis for children who have the following:

- Significant weight loss (or failure to achieve expected weight gain or faltering growth)

- Marked interference with psychosocial functioning

- Nutritional risk or deficiency

- No coincident body image problems

- Disturbance is not due to a medical condition

PFD is a multidisciplinary diagnosis that includes feeding dysfunction in any one or several of four domains:

- Medical

- Nutrition

- Feeding skill

- Psychosocial

There are many reasons PFD is mistaken for ARFID. The main reason is that PFD is a much newer and less widely-known diagnosis. We facilitated the publication of a paper that provided a consensus framework of PFD in 2019. PFD became an ICD code in the U.S. in 2021, over a decade after ARFID. PFD has an international impact because the diagnosis was centered around the international classification of functional disability and health. The PFD diagnosis and subsequent ICD code use the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework. This framework allows the international medical community to evaluate the functional impact feeding has on a child’s activities. It also promotes a multidisciplinary, holistic assessment of how the four domains, medical, nutrition, feeding skill, and psychosocial, interconnect. This ensures the root cause of a child’s feeding challenges are identified.

However, psychologists and practitioners in the eating disorder world tend to know only about ARFID.

Information available on social media is another reason PFD is misdiagnosed as ARFID. Parents concerned about a child’s picky eating can go down a rabbit hole of online information that’s more likely to point to ARFID as online it gets inaccurately labeled as “severe picky eating.” The unfortunate piece to this is that in these conversations about ARFID and severe picky eating, social media presents a misleading picture that fails to take into consideration the medical or feeding skill reasons why a child might have trouble feeding.

Understanding PFD and ARFID

PFD and ARFID in children and young adults share symptoms and behaviors. The child does not eat as much or in a manner expected for a child’s age. The cause and the treatment for this behavior is what varies. Some children with PFD go on to develop ARFID.

A classic case of ARFID is someone with no history of feeding problems before its onset. For example, a child has a choking incident and then is afraid to eat. Another example would be a child with no feeding skills issues but is described as having odd eating habits.

A child with undiagnosed PFD will have a history of feeding issues. These can include any combination of issues, including: allergies, reflux, challenges with bottle feeding, and trouble transitioning to solids.

Treatment for a feeding disorder differs from an eating disorder. For PFD, a clinician will determine if the child is safe to eat. Does he have the skills to chew and swallow? Are there allergies that may be present?

When a child is treated only for ARFID, they’re entering a mental health pathway that can often be difficult to assess and identify if there are other domains present.

Education is vital to improve diagnoses of PFD and ARFID

Education is the key to providing better treatment for children with PFD and ARFID.

We at Feeding Matters are working with clinical experts in the field to help clarify how to determine the correct diagnosis and treatment plan for those who have either PFD or ARFID – or both.

Our goal is that clinicians will better understand both diagnoses so that more patients can be identified earlier and access effective treatment.

Parents need to be aware that PFD can sometimes be misdiagnosed as ARFID or that if PFD goes undiagnosed it can become a more severe ARFID. This knowledge will help more families get treatment from clinicians who understand how to treat PFD and how the two diagnoses overlap.

The earlier we help more families identify the true issue, the more likely we will ensure they get the help they need.

Are you looking for more information? Visit Feeding Matters’ resource page: PFD and ARFID.