Author: Jalenna Francois

Lessons from a career in occupational therapy feeding education and research

Published by Paula Rabaey, PhD, MPH, OTR/L on Apr 22, 2024

Paula Rabaey, PhD, MPH, OTR/L, has seen firsthand how research can improve patients’ lives worldwide over her 30 years in occupational therapy (OT). Dr. Rabaey, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota, has continued working with children throughout her academic career to maintain a direct connection to those who may benefit from her research.

Since her first occupational therapy position, when she was introduced to the role of OT in feeding children with cerebral palsy and other neurological developmental delays, mealtime participation as a major childhood occupation has been Dr. Rabaey’s passion. Working with families in her area and on her volunteer trips abroad has given Dr. Rabaey a direct connection to families’ feeding therapy needs. She also can see how educational experiences and academic research can profoundly impact service delivery.

How education and research in occupational therapy improves feeding therapy methods

An early example of how education informed her practice was evident after attending a multi-day continuing education course focused on strategies to foster feeding skill development. “The course was life-changing because it made me think about the multiple steps to eating, from getting the food on your plate to getting it to your mouth,” says Dr. Rabaey.One child born with a cleft palate and later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder stands out in particular. At age two, the girl’s feeding difficulties were so profound that she would scream at the sight of her high chair. All of her medical feeding needs had been addressed, but she still refused to eat.

By the time I met with her, numerous therapies had failed to help, and the little girl was getting all of her nutrition from a gastrostomy-tube. Her family was wary of therapy but desperate for a solution that could offer a more typical eating experience.

Dr. Rabaey worked with the entire family using the skills she learned from her feeding coursework. For nearly a year, they worked through the toddler’s tactile aversions and slowly introduced food and witnessed remarkable progress. “By the time I discharged her, she was eating pretty much everything by mouth. She started attending school and was thriving,” Dr. Rabaey said.

It was an important early lesson on the power of working with the whole family while advocating for the child’s unique needs.

Researching abroad to benefit children with pediatric feeding disorder worldwide

Much of Dr. Rabaey’s research comes from her OT work abroad with SPOON. She’s dedicated to using a mixed methods approach of qualitative and quantitative research methodologies to understand the complexity of pediatric feeding disorder and its impact on children and families.With SPOON, she volunteers as a feeding technical expert and helped develop an assessment tool for caregiver feeding practices in orphanages. The tool offers solutions for positioning, cup and spoon use, modification of food textures and responsive feeding practices for caregivers who feed children with disabilities. She continues researching the tool’s efficacy and usability and has presented the work in Mongolia, Kazakhstan, China and Russia.

Dr. Rabaey also has helped develop a training of trainers (TOT) curriculum for community health workers working with families with a child with a disability in Zambia and is assisting SPOON with piloting a unique and low-cost feeding chair for use in low and middle-income countries. This work has informed how she teaches her students to practice with multicultural families in the U.S. today. There are so many cultural elements to eating; “You have to be empathetic to consider every family’s way of doing things,” she says.

How research informs our work at Feeding Matters

As the research pillar at Feeding Matters, Dr. Rabaey leads our research initiatives as well as how research informs our evidence-based practice recommendations. Research was key to establishing an International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code for PFD. The code was made official in October 2021 after the council published a consensus paper, advocated for a diagnostic code within the ICD and disseminated the information to the healthcare community.

Since then, Dr. Rabaey collaborated with Kate Barlow, OTD, OTR/L, IMH-E on a mixed-method study through a Feeding Matters grant to identify what assessment tools therapists are using to diagnose PFD. “You don’t pull out a standardized kit from the shelf to evaluate feeding,” she says.

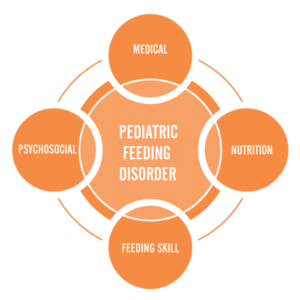

That research was published in 2023, showing that OTs and speech pathologists use a mix of ways to evaluate PFD, and not many of the assessments are standardized. The tools don’t necessarily fit the four domains of pediatric feeding disorder: medical, nutrition, feeding skill and psychosocial. “What’s clear is we need to have a broader, more formalized way to assess the complexity of PFD,” says Dr. Rabaey.

While there’s more work to be done to improve feeding therapy practices through research, Dr. Rabaey is proud to see how far feeding therapy has come since she began as an OT.

“There is a great need for evidence and evidence-based practice. While it’s slow going, I think we’re making important strides.”

Paula Rabaey is the research pillar at Feeding Matters and a new fellow for AOTA. She’s on the Medical Advisory Board and a feeding technical expert for Spoon Foundation. Many of her numerous academic publications focus on her international research.

Learning to Breathe

Published by Athena Flicek on Apr 10, 2024

I could feel my blood pressure rising. You might wonder if I was about to run a race or perform a medical miracle. All I was doing was sitting at the dining table for lunch with my 4-year-old son. Looking at his sweet face. My eyes staring back at me. All of a sudden, I couldn’t breathe. He had bitten off a large piece of chicken. I was waiting for him to struggle to manage it. It sent me into a familiar spiral, presenting me an image I had been confronted with since he was an infant. Him struggling in front of my very eyes. He did amazing, as usual. And in that moment I realized that I needed help.

No one had told me I needed help up to this point. They could see it but they remained silent. They saw me struggle to leave my bedroom or to wash my hair. I would tell them I hadn’t brushed my teeth in over a week, and honestly, if you know me (a child who had braces, an expander, a retainer, and lover of floss and white strips) this would be the most obvious scream for help. Yet nothing. Nobody knew what to say or what to do.

But today was different. Today I could feel my anxiety clawing to get ahold of my child. And I knew I had to get help. I was 39 when I searched for support. It took me a year to build up the courage to schedule an appointment. It was my 40th birthday present to myself. Speaking of birthday’s, let’s get back to a very important one: my son Ari’s.

I had a beautiful pregnancy. Then came the struggle. Over the first 48 hours I heard him constantly struggle to clear his amniotic fluid. I would freeze up. His dad would grab the suction and get it out. When they told us we could go home I had a gut feeling that something wasn’t right. I felt like my son needed more testing or help.. I didn’t know what, but something felt off.

Over the next 18 months Ari would projective vomit across the room after every meal. He couldn’t sleep laying down. Every visit to his pediatrician’s office ended in tears. “It’s just spit up,” they said. Well, I knew that wasn’t true. My child’s body was violently refusing milk and certain foods. But here I was, trying to airplane an unwanted food into his mouth. At the end of one visit my son’s doctor casually said “You might want to try this local nonprofit, they might have some resources to help.”

I hurried home, went to their website, and all I could see was their beautiful orange “Get Help” button. I clicked on it seemingly 300 times. They had a simple 6 item feeding questionnaire to complete and be able to tell if your child might need help. If you answered affirmatively to 2 of the 6 it directs you to help. I answered affirmatively to all 6 and immediately started crying. My son Ari has pediatric feeding disorder. You might wonder what that is. It’s a child who isn’t eating in an age-appropriate manner. Ari also has EoE (eosinophilic esophagitis) and sensory processing disorder (PFD). He is curious, fast, a born performer, comically inclined and wants to build robots that he can accompany to space one day. I quit my job as an elementary school teacher to take him to therapy and help him find joy in food instead of fear.

It was the beginning of the end for many things for me: my marriage, my first career. But it was also the beginning of a new and amazing experiences.

Ironically, right before I started therapy, I saw a job posting from the same non-profit that I felt had saved me and my son. It was for someone to plan their annual pediatric feeding disorder educational conference. I didn’t tell anyone about it. And then I made it to the third round. I will never forget that phone call and subsequent job offer. They gave me a gift. A gift I will never be able to repay. Planning a pediatric feeding disorder conference for families and professionals is part of my therapy.

I feel like we are all given gifts. Ari was another one. He has taught me that his journey is not mine. I’m just a guide. My anxieties, should not be his. And my therapist likes to remind me I’m not a doctor, a mind reader or a fortune teller. I need those daily reminders. Therapy has taught me to avoid negative thoughts, be independent instead of co-dependent (and yes, this includes how we interact with our children), and to live in my calm, peaceful place.

I finally took my first deep breath two months ago. I could tell it was different. I am not a failure because I couldn’t feed my child. I am a success because of it.

Living our Values: Collaborative, Innovative, Inclusive

Published by Jaclyn Pederson, MHI on Feb 29, 2024

As I sit down to pen my thoughts to share with you this month, the importance of trust within our community is top of mind. Your trust in us is the anchor of our organization, and it’s a responsibility we take seriously.

In recent weeks, we’ve actively sought your feedback on various aspects of our work – from refining our storytelling and awareness initiatives to enhancing support structures for families and advancing educational initiatives. Your responses, deep in insight and wisdom, are shaping the trajectory of Feeding Matters. It is your trust and openness that empower us to make the necessary adjustments, both big and small, ensuring that we remain, a community-driven organization.

Our commitment to continuous improvement goes hand in hand with nurturing the trust you place in us. We recognize that trust is earned through transparency, active listening, and responsive action. As we navigate the complexities of pediatric feeding disorder (PFD), our goal remains resolute: to transform the field through education, advocacy, research, and support.

As we bid farewell to this month, I believe it also important to acknowledge and celebrate the significance of Black History Month in the United States. While we celebrate the achievements and contributions of Black individuals and leaders who have shaped our world and inspired positive change, we must also acknowledge the systemic barriers and disparities that impact marginalized communities, including Black children and families.

This is especially true within the PFD system of care. In our mission to empower families and transform the PFD system, we understand that this requires a collective effort grounded in compassion and understanding. This Black History Month, Feeding Matters recommits itself to amplifying the voices of marginalized communities. Your feedback allows us to do this and your trust in us to learn and make continuous changes is vital. Together, we can work for equitable access to resources, education, and support for every child affected by PFD, both within the United States and globally, all while respecting and honoring the trust you’ve placed in us.

We have the power to shape a more just, compassionate, and equitable future for children, inclusive of all races, ethnicities, and backgrounds. Thank you for entrusting us with this vital mission and for being an integral part of our community.

Best,

Jaclyn Pederson, MHI

CEO

Do you have feedback to share with us? Email us at info@feedingmatters.org, we want to hear from you!

Feeding Matters Values

Collaborative

We partner to ensure every voice is heard, ideas are openly shared, and we work towards a common goal.

Innovative

We take the initiative to leave comfort zones, embrace new ideas, and generate change.

Inclusive

We lead with trust and empathy to invite and value all perspectives.

Building a care team for PFD

Published by Erin Ross, PhD, CCC-SLP, CLC on Feb 26, 2024

In Washington state, every child supported by early intervention (EI) for pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) is treated by a team that includes a nurse, dietitian and a speech and language pathologist (SLP) or an occupational therapist (OT). The clinicians work together to coordinate care and discuss each child’s needs. It’s a model of care that works –– but is also extremely rare.

Many states are moving in the opposite direction for EI –– providing children ages 0-3 with services from a single provider. This may be a physical therapist (PT), OT or an SLP. That clinician is expected to cover every area of the child’s developmental therapy. Even with the best intentions, clinicians will fall short of providing the comprehensive care required for PFD.

Outside of feeding clinics and children’s hospitals, many children with PFD are treated by a patchwork of clinicians who don’t easily coordinate care. Those who seek a spot in a feeding clinic face long waiting lists and typically experience severe symptoms of PFD.

Finding support for four domains of PFD

Pediatric feeding disorder affects four domains of feeding:

- Feeding skill: Actual feeding skills, such as chewing and swallowing and managing the sensory aspects of eating

- Medical: The body’s physical ability to digest food

- Psychosocial: Learned ability to eat without distress

- Nutrition: Willingness to eat a variety of foods with high nutritional value

Feeding Matters’ Coordinated Care Model examines the complexities of PFD through these four key domains that significantly impact a child’s lifelong well-being. Because PFD is so multidimensional, children need support to cover each domain. This requires a multi-disciplinary care team.

PFD can be well-regulated and treated through collaborative care and the proper support system. But for many parents, the job of cobbling together a PFD care team falls upon them.

Designing the all-star PFD care team

Symptoms of PFD vary for every child. Some common ones include a lack of interest or refusal at mealtimes, extreme picky eating and slow weight gain. If this sounds familiar, know that it’s not okay if mealtimes are a constant struggle. Unfortunately, some providers may discount these behaviors. A good rule when working with any clinician is that if you are worried, this means there’s a problem.

If you are building a care team for your child with pediatric feeding disorder, seek support from clinicians who can cover the four domains of feeding. Consider finding support from pediatric clinicians who work on telehealth if you live in an area with limited options.

Medical domain

This provider has expertise in your child’s overall medical health, such as a pediatrician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant. Their job is to identify when feeding needs additional assessment. If your child shows signs of PFD, you’ll need a provider who understands the disorder and the four domains that make up the coordinated care model.

Feeding skill domain

An OT or SLP with expertise in teaching the skill of feeding is an important member of your PFD care team. They’ll focus on the development and coordination of the sensory and movement skills that eating requires.

There’s overlap in the feeding skills and OT and an SLP can support, so be sure to describe your child’s challenges with the clinician. Ideally, you can work with both as they each bring expertise. Look for an OT and/or SLP with expertise in sensory and oral motor skills.

Psychosocial domain

Mental health providers, such as a psychologist or a licensed social worker, can help assess and treat the learned avoidance behaviors typically seen with a pediatric feeding disorder. For the child, this means managing mealtime behaviors and learned responses. This also includes modifying caregivers’ responses to the child’s behavior to promote a positive and successful feeding interaction.

Nutrition domain

It’s important to distinguish a registered dietitian (RD) from a nutritionist. In most states, individuals call themselves a nutritionist with no formal education or medical licensure association. Look for an RD with pediatric experience. Many RDs work over telehealth.

Finally and most importantly, you, as the parent, are a key member of the multidisciplinary team. You know your child best. It’s important you feel the team is listening to you and not just talking at you.

Tips for coordinating your child’s care

Ideally, your child’s care team will communicate on their own. When this doesn’t happen, serving as a middleman for provider communication is challenging. Ask your child’s clinicians to follow up with one another rather than passing messages and forms through you.

Tell the practitioner that you would really appreciate it if they would contact the other clinician. When your child is able to go to a multi-disciplinary team under one roof, that’s how they would function. Even when that’s not the case, you can still set that as the expectation for your child’s care team.

Most importantly, trust your gut. Many people are raised to think physicians are going to direct care. This is often true, but if you feel a provider is missing something or you want a second opinion, you are your child’s advocate.

If you think feeding is a problem, it’s a problem.

To find a licensed professional in your area, visit the Feeding Matters Provider Directory.

Dr. Erin Ross is a practicing SLP and the owner of Feeding Fundamentals, an organization that provides evidence-based professional training to advance the practice of infant feeding. She is a long-time member of the Feeding Matters Founding Medical Professional Council.

Feeding Matters Receives Transformative Grant

Published by Feeding Matters on Jan 31, 2024

Feeding Matters recently received a generous grant from the Diane & Bruce Halle Foundation to transform early identification in Arizona and enhance world-wide awareness for pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). For a child with PFD, every meal becomes a source of anxiety and frustration. For families of children with PFD, parents feel like failures, isolated with their mental and financial health suffering with each bite they try to get their child to take.

This transformative grant will fuel a comprehensive 5-year strategic plan designed to revolutionize outreach and awareness for children with PFD, significantly enhancing early intervention (EI) and access to care. Leveraging existing partnerships in Arizona, the project will focus on collaborative intervention efforts, systemic initiatives, the launch of innovative awareness tools and the identification and elimination of barriers hindering children with PFD.

Families seeking specialized care for their children with PFD often confront extended wait times, resulting in delayed intervention and adverse health outcomes. With challenges in qualified team members and a lack of a PFD screening process, Arizona’s Early Intervention (EI) system faces hurdles in providing timely and effective care. The work this grant will allow aims to bridge these critical gaps by undertaking a comprehensive outreach and partnership strategy. This includes a focus on serving traditionally underserved communities, such as LatinX communities, low-income areas, and indigenous communities that often have challenges accessing feeding intervention.

Activities that this grant will enable:

- Arizona outreach and system advancements: Conduct targeted outreach to support early identification and resources for families.

- Launch several initiatives aimed to enhance early identification and increased access to services inclusive of strategic partnership, medical school partnership, an established screening process and quality assessment framework, and a family waitlist program.

- Awareness campaigns and educational tools: Launch the “It’s Not Picky Eating Campaign” leveraging social media, high-quality videos, and blog content. Develop infographics, a patient journey map, and a PFD documentary to increase public understanding.

- Publications and Resources: Revise the Family Guide with comprehensive and up-to-date information on PFD. Publish a book explaining PFD and allowing children with PFD to feel represented, seen, and included.

This support marks a watershed moment for Feeding Matters, with the potential to revolutionize the landscape of early identification and assessment not only in Arizona but globally. With an anticipated 30,000 individuals served in the first year and a commitment to exponentially grow its impact through targeted outreach, the project is not just about immediate change but represents a seismic shift in the landscape of early identification and assessment practices.

“The generous support from The Diane and Bruce Halle Foundation is a pivotal milestone in our ongoing mission at Feeding Matters. Through this transformative grant, we are strategically advancing our commitment to making pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) a household name by 2026. This game-changing project not only sets a new standard for early identification and intervention but propels us significantly closer to achieving our goal of widespread awareness. As we embark on this journey, these projects empower us to create a lasting impact, touching the lives of thousands of individuals and fostering a legacy of awareness and support that will resonate for years to come,” shared Jaclyn Pederson, CEO of Feeding Matters.

About Feeding Matters

For kids with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD), every bite of food can be painful, scary, or simply impossible to swallow, potentially impeding nutrition, development, growth, and overall well-being. Yet, there is no functional system of care for PFD locally, nationally, or internationally. That’s why Feeding Matters is dedicated to creating a world where children with pediatric feeding disorder will thrive. Established in 2006, Feeding Matters is the first organization in the world uniting the concerns of families with the field’s leading advocates, experts, and allied healthcare professionals to ignite unprecedented change to the system of care through advocacy, education, support, and research – including a stand-alone diagnosis, the International Pediatric Feeding Disorder Conference, and the Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire. In 2021, Feeding Matters reached nearly 200,000 individuals in 50 states and 143 countries through their programs and website. To learn more about pediatric feeding disorder, visit feedingmatters.org or follow us on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube at @FeedingMatters.

About The Diane & Bruce Halle Foundation

In 2002, Bruce and Diane Halle founded the Diane & Bruce Halle Foundation to extend that sense of caring to the larger community. The Halle Foundation now serves as a statewide leader in providing philanthropic resources for organizations working in the fields of human services, health & medical, education, arts & culture, and spirituality. The Halle Foundation identifies and funds outstanding nonprofits to ensure that all people can build healthy, productive, and inspiring lives.

Behind the headlines: Exploring the complex world of tongue tie releases and pediatric feeding disorder

Published by Feeding Matters on Jan 29, 2024

A tongue tie release procedure (frenectomy or frenotomy) is increasingly prevalent among children with pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) that the majority of them have had it, or their parents at least considered it.

That’s because difficulty breastfeeding is common among children with PFD. A frenectomy is often considered an early treatment to improve latching while breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding is a complicated process that doesn’t come naturally to all mothers and babies. It takes multiple muscles, the ability to coordinate sucking and breathing and the strength to stay awake through strenuous exercise. Releasing a tongue tie can seem like an easy fix.

But for kids with PFD, a frenectomy doesn’t necessarily fix feeding problems and is instead one step along a journey of treatment when the frenulum is not the sole cause for feeding dysfunction. For some babies, a frenectomy can be helpful. For others, it’s not necessary. And in some rare cases, the elective procedure causes harm. While generally safe and often performed by dentists, the procedure maintains the potential to do harm, without a significant assurance of benefit. The procedure is sometimes not covered by insurance and can cost hundreds of dollars.

The debate about releasing tongue ties recently was brought to the forefront in The New York Times article, Inside the Booming Business of Cutting Babies’ Tongues. Showcasing many cases where the procedure was unnecessary or went wrong, the article paints a picture of a procedure as controversial as it is common.

Tongue tie releases for children with pediatric feeding disorder

What’s clear from working with countless families of children with PFD is the benefits of a frenectomy vary on a case-by-case basis. Most importantly, it should never be a result of a self-referral to a clinician who advertises the procedure as the obvious answer for breastfeeding difficulties. Instead, the decision should be shared by the family and a qualified clinician.

Nikhila Raol, MD, MPH, pediatric ENT and an associate professor at Emory University School of Medicine who researches ankyloglossia, or tongue ties, says getting the procedure is a multifactorial decision, meaning it

takes careful consideration with advice from multiple clinicians working together. “Even when the tongue tie is physically obvious, I’m still a proponent of having a functional evaluation with a feeding therapist or lactation consultant with real expertise in evaluating feeding and latch before a procedure. What I’m finding in my ongoing research is that even if a baby has a tongue tie, if the mother’s breast shape is favorable, it may not cause as much issue as we think,” she says.

Breastfeeding often takes some time for babies and moms to adjust. Dr. Raol recommends most parents wait at least two weeks to a month of trying ways to adjust to breastfeeding before getting a frenectomy on a newborn, assuming that the weight gain is acceptable. “Sometimes, you just have to give the baby time to figure it out and the mom’s body to adjust to breastfeeding. Figuring out how to latch and how to get a strong suck sometimes just get better with time,” she says.

Jaclyn Pederson, CEO of Feeding Matters, sees many parents consider the benefits of a frenectomy when breastfeeding or picky eating is challenging. As a parent, she did the same and released the tongue tie on one of her sons. She says that while a tethered tongue is a concern, what can get lost is the nuance that it’s one concern of many –– especially when a child is diagnosed with PFD. “What we know about PFD is that it’s incredibly complex. One of the first things that we share with families is helping them understand that there’s not just going to be a switch that’s flipped to make their feeding journey easier. It’s a series of small milestones that build over time,” she says.

The challenge of considering a frenectomy as a quick fix to difficulty breastfeeding is not just disappointment when it doesn’t work. It can mean overlooking the actual root of the problem, such as some other problem with feeding or swallowing. “Assuming that the surgery is the solution, even as minimal of a procedure as it is, still leaves out a lot of other feeding components,” says Pederson.

One family’s tongue tie release story

When Emily Garlinsky’s son, Landon, had trouble breastfeeding, she was at first confident a tongue tie wasn’t the issue. Clinicians in the hospital when he was born, as well as her pediatrician, assured her his tongue looked normal.

But as Landon continued to struggle and Emily shared her feeding frustration in Facebook groups, she kept hearing people recommend a tongue tie evaluation. By the time Landon was four months old and still struggling to feed, Emily thought it was time to revisit the issue. Landon was already in feeding therapy at that point, and his therapist agreed the procedure might help.

Emily went to a pediatric dentist who told her Landon had a lip tie and a tongue tie. Landon underwent the procedure, but his feeding didn’t improve. He did well with the surgery, though, and Emily is glad they did the release. “There’s a lot of back and forth on Facebook groups from people who regret it. It didn’t help with feeding for us, but other aspects of the release are helpful for speech,” says Emily.

True or false? Tongue tie myths

Dr. Raol warns against peddling fear to encourage parents to act for their babies or overpromising treatment results. “You must be careful because breastfeeding mothers are a vulnerable population. A new mother just wants to do her best,” she says.

Following are some common assumptions around tongue tie release procedures. Some have no research evidence to support them, and others have emerging research.

Tongue ties cause swallowing difficulties: Maybe

Dr. Raol is rigorously studying this in her research. She says, “When you swallow, your tongue starts the pharyngeal squeezing process. When a child can’t squeeze hard, we think this could cause food or liquid to spill into the airway as it is trying to enter the esophagus.”

Tongue ties cause reflux: Unknown

Reflux is normal in babies due to low tone of the sphincter muscle that separates the stomach from the esophagus. Dr. Raol explains that it has never been objectively demonstrated that a tongue tie is responsible for this through aerophagia, or swallowing air, which is the proposed mechanism. However, some studies have shown that reflux symptoms improve after frenectomy. What we do not know is if the symptoms would have just gotten better with time.

Tongue ties cause problems with craniofacial development: Maybe

There’s not a lot of existing research evidence to support this. More research is needed.

A laser is better than clipping for a tongue tie release: Maybe

Many parents hear on social media advice to go to a pediatric dentist instead of an ENT for a tongue tie release because dentists use a laser.

More research is needed, but a review of the existing research found the laser procedure resulted in a shorter surgery, without suturing, and less postoperative pain.

Tongue ties cause speech issues: Maybe for some

The jury is still out on this because Dr. Raol explains there is a deficiency in the literature. Most of the research comes from English-speaking countries, but there’s a difference in how the tongue works in other languages. “In Indian languages, we use the tongue a lot more with certain sounds where you put your tongue far back on the palate. In India, the primary reason kids get a frenectomy is for speech.”

For serious speech issues, though, says Dr. Raol, a tongue tie release is not a quick fix. “In the case of expressive aphasia or something like that, we should not be telling families that clipping a tongue tie will solve that problem,” she says.

You should go to a pediatric dentist for a frenectomy: Only with a diagnosis or consultation from an ENT, lactation consultant, feeding skill specialist, or pediatrician first –– and in that case, the ENT or a pediatric dentist could do the procedure

Breastfeeding is complicated, and any issues should be evaluated by an expert who considers both the baby’s and the mother’s anatomy. Misdiagnosing a tongue tie as the issue can mask other underlying problems, such as PFD.

While it’s true that a frenectomy is a minor surgery and a trained clinician can safely manage the procedure, it still requires careful consideration.

Be wary of a clinician who promises the procedure as a quick fix in exchange for out-of-pocket payment.

Signs your child might need an evaluation from a feeding therapist or lactation consultant

While some children’s tongue ties are apparent even to the untrained eye, it’s still important to get a thorough evaluation before scheduling a frenectomy. Under no scenario should you self-refer or decide based on advice from a friend or a clinician on social media. While this may seem obvious, many people are doing just that and then paying cash for the elective procedure. “We’ve seen this become the number one thing families are thinking about when they have trouble breastfeeding because they hear their friends talk about it and see it online,” says Pederson.

Following are some signs your child might be a good candidate for a frenectomy:

- Your child is not steadily gaining weight from breastfeeding.

- There is some tongue tethering.

- Pain while breastfeeding goes beyond the initial adjustment period.

- You’ve tried various positions and breastfeeding techniques.

- The number of times your child feeds per day remains the same over time. Your baby should become more efficient at feeding as she grows.

When seeking the right clinician, Pederson recommends starting with your pediatrician and an ENT, who will conduct a thorough evaluation. “Look for a professional who shares the pros and cons of a scenario versus one who pushes a treatment as the answer to everything. Explaining the nuance is how you know that a professional really understands how complicated tongue ties are and the issue of feeding is in general,” she says.

Like any treatment or therapy for children with PFD, managing feeding requires a degree of personalized medicine. “Some kids really do need a frenectomy. But if all I have is a hammer, everything is a nail. The tongue is just one piece of the puzzle,” says Dr. Raol.

In the end, getting even a minor tongue tie release surgery is a decision parents should make based on clinical advice, says Dr. Raol. “If you’ve tried everything, and there does seem to be some tethering, and you’re fully aware that this may or may not help, then I don’t think the procedure is unreasonable.”

Feeding Matters blog posts are written by the communications team at Feeding Matters and designed to continue the conversation and awareness around pediatric feeding disorder based on expert opinion interviews.

Unlocking Hope: Join the Feeding Matters Family-Centered PFD Research Consortium

Published by Brandt Perry on Feb 12, 2024

Are you a parent or caregiver navigating the complexities of Pediatric Feeding Disorder (PFD)? If so, you’re not alone. As a parent of two children facing these challenges, I intimately understand the hurdles that come with this condition. I’m thrilled to share an exciting opportunity that could reshape the future for families navigating PFD – the Feeding Matters Family-Centered PFD Research Consortium.

Understanding the Landscape

Feeding Matters, an organization close to my heart, is a world leader in the PFD field. Having actively volunteered and chaired the Family Advisory Council, I’ve witnessed firsthand their dedication and impact. Now, the Feeding Matters is taking a significant step forward with the Feeding Matters Family-Centered PFD Research Consortium.

A Personal Stake in Progress

As a parent deeply involved in this initiative, I am serving as the Primary Family Stakeholder Consultant. Leveraging my personal experiences, I’m working to ensure that the Consortium’s efforts authentically reflect the needs and perspectives of families like ours. This unique approach, engaging PFD families from the beginning, underscores Feeding Matters’ commitment to family-driven care and patient-centered research.

Consortium Goals Aligned with Transformation

The Consortium’s objectives are essential for progress. From member training to consensus on research priorities and sustainable engagement, each goal aligns seamlessly with the mission and values of Feeding Matters. Joining the Feeding Matters Family-Centered PFD Research Consortium means contributing to transformative PFD research and improving outcomes for our children and families.

Join the Movement

This Consortium is more than a research initiative; it’s a beacon of hope, empowerment, and collaboration. By participating in a research project, you contribute valuable insights that will use to develop more effective therapies, diagnostic tools, and support systems for families navigating the complexities of PFD. Your involvement can drive positive change in the lives of countless children and their parents.

By becoming a part of this vital endeavor, you’re actively contributing to a movement that has the potential to redefine the future for families dealing with PFD.

How can get involved?

- Become a Consortium Member: Join a community of parents, caregivers, and advocates dedicated to making a difference in the PFD landscape.

- Spread the Word: Share this opportunity with your network. The more families we involve, the greater the impact.

- Stay Informed: Subscribe to Feeding Matters updates to stay informed about the consortium’s progress and other PFD-related developments.

- Connect on the Feeding Matters App.

Conclusion

Join me and countless others in supporting the Feeding Matters PFD Research Consortium. Together, let’s unlock hope, drive empowerment, and foster collaboration. We can contribute to a brighter and more informed future for our kids.

For more information and to join the Feeding Matters Family-Centered PFD Research Consortium, visit feedingmatters.org/consortium

New Clinical Tool Available

Published by Feeding Matters on Dec 19, 2023

A new clinical tool has been authored by MAJ Patrick Reeves MD, FAAP.  The Clinical Action Plan for Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition is a free open access resource designed to simplify knowledge transfer on enteral and parenteral nutrition from the medical team to the child and family. These types of tools address health literacy challenges by creating a method in which to share complex information in a concise and easy to understand format.

The Clinical Action Plan for Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition is a free open access resource designed to simplify knowledge transfer on enteral and parenteral nutrition from the medical team to the child and family. These types of tools address health literacy challenges by creating a method in which to share complex information in a concise and easy to understand format.

View a FREE presentation on how to use the tool here.

My PFD Story: Georgio

Published by Gia Licata & Nicholas Matthews on

We tried for over a year to get pregnant and we couldn’t have been happier when we found out I finally was. After many loses, medications, and tears.. our miracle baby was here. Something wasn’t right though, and I knew that from the minute I found out I was pregnant.

They diagnosed me with Polyhydramnios and told me there was nothing to worry about. Right. After googling for days, I was reading a lot of baby’s having swallowing issues in links to the polyhydraminos. This worried me a lot and I spoke with my doctor and she reassured me that that wouldn’t happen. Georgio was born at 35 weeks and spent 5 days in NICU. As I mama, I knew something just wasn’t right. He was vomiting his feeds, super fussy and something just really seemed off.

On January 5, 2023 Georgio was hospitalized for ten days after he completely stopped eating. A bunch of tests showed that he had dysphagia and was unable to safely eat. By April, he had a G-tube put in and I really believe that’s the day our journey truly began.

Running to the grocery store is no longer a simple task. Routines don’t exist. Date nights aren’t even an option. Snuggling rarely happens. To say our hearts are broken, is an understatement. I sat in that space for months. But then I realized that my 4 month old was now a 10 month old. Time went. I stayed in that space, but time moved forward. That’s when I realized that I had to just come to terms with this being the way it is.

I like to say for now. I like to have hope. I have to say that things have gotten better. My son was on basically a continuous feed all day and now gets 3 feeds each day and 1 overnight. We have gotten his overnight down to 5 1/2 hours and we also even managed to get him feeding safely in his crib.

I worry everyday that my son won’t have a “normal” life, but I try to remember that this is HIS “normal”. He doesn’t know any different. He’s the happiest baby, always laughing. That’s where I find that hope I was talking about. You have to stay hopeful, because at the end of the day they need us.

I remember the days where I would cry because I knew my baby was going to be hospitalized for dehydration because I couldn’t get him to drink. Now, I know he’s eating. He’s healthy. He’s gaining weight. We have to remember that even though things are different, our babies are fighters. They’re strong. They’re resilient.

Georgio is a true miracle. He lights up every room he is in. He truly is the strongest kid I know and will forever be my hero.

My PFD Story: Ashley

Published by Ashley Collier on

My daughter was a 33-week preemie and hated to be fed. We were discharged from the NICU without reliable feeds and tried to outrun a feeding tube for years. She got one when she was 2 1/2 and made tremendous progress. We also fumbled with some not-so-knowledgeable professionals who should have known better, but we finally found a good feeding team when she was 2.

My daughter was a 33-week preemie and hated to be fed. We were discharged from the NICU without reliable feeds and tried to outrun a feeding tube for years. She got one when she was 2 1/2 and made tremendous progress. We also fumbled with some not-so-knowledgeable professionals who should have known better, but we finally found a good feeding team when she was 2.

After intensive feeding therapy at age 4, we got to wean off the tube and she is now eating typical food in an almost typical way. She has overcome GERD, oral motor issues, slow motility, texture and flavor aversions, and all the learned associations from those.

It’s been quite a journey and as were living it there was nobody to connect with to try to find a better way or just a place to vent. I volunteer now — my daughter is 15 — to help make sure no family after us fumbles the way we had to.